History of Wyoming/Modern Wyoming, 1890-1945

Wyoming Statehood

[edit | edit source]

Until neighboring South Dakota and Montana entered the Union in 1889, Wyoming received little recognition due to its relatively small population. Wyoming had not considered entering the United States as a state due to some prominent citizens not believing the territory was ready to become a state. However when the issue came to a territory wide vote, the majority of Wyoming’s citizens voted in favor of statehood. In Governor Frances E. Warren's inauguration speech, a plea was made for statehood. Warren argued that the increased expense of statehood would be offset by greater revenues, and promised rapid growth and development once admission to the Union had been accomplished. In September of 1889, under the leadership of Governor Francis E. Warren, Wyoming elected forty-nine men to the Constitutional Convention, where the soon to be state's constitution was drafted. On July 10th, 1890, the United States admitted Wyoming into the Union as the forty-fourth state.

The Johnson County War

[edit | edit source]The Johnson County War was a two-day range war fought between large cattle ranchers and small homesteaders in northern Wyoming in the spring of 1892. Like most range wars of the Old West, the Johnson County War - sometimes referred to as the War on Powder River - was the climax of longstanding property disputes over land and especially cattle ownership on the open range. Today, the story of the Johnson County War is one of the most retold and well known of the range war tales. The conflict has been referred to as “the most notorious event in the history of Wyoming,” for its influence in reshaping the cattle industry and political landscape of Wyoming.

Background

[edit | edit source]Crowding and Competition on the Open Range

[edit | edit source]In the late 19th century, the range cattle industry was the undisputed king of Wyoming business. Encouraged by the booming industry and supported by federal land acts of the time (especially the Homestead Act of 1862) homesteaders migrated to Wyoming to share in the public domain and raise small herds of their own. By the early 1880's, this migration had created a major crowding problem on the range. The land-intensive nature of cattle ranching and informal land rights (based mostly in common law) brewed conflict and competition between established ranchers and new-coming homesteaders. Exacerbating this issue, the price of cattle reached a record high in 1882 and cattlemen responded by bringing in more cattle and overstocking their ranges. This led to a sharp rise in cattle population and a rapid decline in available land. Rustling - illegal branding/theft of cattle - became more of a concern (especially among big cattlemen), as cattle from different herds mixed. Theft, however, was not the only source of conflict on the increasingly crowded range.

Wyoming Stock Growers' Association

[edit | edit source]Frustrated by growing competition from homesteaders, big cattlemen – all members of the Wyoming Stock Growers Association (WSGA) – attempted to limit settlers’ access to the public domain by influencing territorial legislation (Maverick Law of 1884) and by controlling participation in the annual roundup. Unfortunately for the cattlemen, the WSGA’s efforts did not effectively curb rustling and in 1892, Johnson County homesteaders formed the rival Northern Wyoming Stock Farmers and Stock Growers Association, promising to host an alternate roundup. This direct competition with the WSGA and the persistent issue of rustling led a group of big cattlemen to seek an end to their competition through vigilante justice in the spring of 1892.

The Invasion and the War on Powder River

[edit | edit source]

Nate Champion was a small cattleman who ran his small herd on public lands, which, under the Homestead Act, were legally open to him. The big cattlemen attempted to assassinate Nate Champion in 1891, but that attempt failed miserably. Champion would later testify against the cattlemen, further aggravating the existing rivalry between cattle barons and homesteaders. On April 5, 1892, a small militia of prominent Wyoming cattlemen, their employees, and 23 hired Texas gunmen traveled north from Cheyenne to Johnson County with a “death list” of roughly 70 accused rustlers and troublemakers. The “invasion”, as it has come to be known, was bound for Buffalo, the seat of Johnson County, but was permanently delayed at the T.A. Ranch on Powder River on April 8, 1892. With intelligence provided by local spies, the militia discovered that Champion was hiding out at the K.C. Ranch. At the ranch, the invaders and Champion engaged in a shoot-out that lasted many hours before the militia managed to set fire to the cabin, forcing Champion outside where he was fatally shot. The invaders fled to the nearby T.A. Ranch.

News of the invasion spread, soon reaching Johnson County Sheriff, Red Angus, who quickly raised his own vigilante army of around 200 men to combat the invaders. This group of men planned to deploy a strategy called an "ark of safety" (a moveable fort to which dynamite was attached) to force out the invaders from the T.A. Ranch. Unfortunately, the group never was able to use this tactic. The standoff between the invaders and Sheriff Angus’ army lasted only two days before the intervention of the 6th U.S. Cavalry on April 13th, 1892, brought the fighting to an end. President Benjamin Harrison ordered the dispatch of troops from Fort McKinney, under Article IV, Section 4, Clause 2 of the U.S. Constitution, which allows for the use of U.S. military force under the President's orders for protection from invasion and domestic violence. The invaders were taken into custody in Cheyenne to await judicial action, and the conflict known as the Johnson County War was ended. However, the impact of this War in Wyoming had only just begun.

Aftermath: Justice, Politics and the New West

[edit | edit source]

Later testimonials of the invaders and their supporters have stated that then-governor of Wyoming, Amos Barber knew of the planned invasion through many of his cattle baron friends. Hearing of his friends’ predicament in Johnson County, Barber called upon President Harrison for military intervention. Barber assumed control of the invaders’ questioning once they were taken into custody. Though charges were brought against the invaders, none were ever convicted.

The invasion had a major political impact in Wyoming, where voters were disturbed by the lack of legal consequences brought against the invaders. In the 1892 election the Republican Party, long associated with big cattlemen and the WSGA, was ousted by a landslide victory for Wyoming Democrats in the seats of governor, Congress and Senate.

The Johnson County War also marks a significant shift in the Wyoming cattle industry, from the days of the Old West and the kings of range cattle, to the New West of the pioneering homesteader.

Wyoming and Oil

[edit | edit source]Oil Boom and Demographic Shift

[edit | edit source]After the Johnson County War came to an end and Wyoming entered into the early twentieth century, the state began to shift away from its traditional cattle industry towards a new resource. Discoveries of oil reserves in the state sparked the growth of what would prove to be a much more lucrative industry.

The growth of the oil industry in Wyoming would come to have very important economic and political ramifications for the state. In the early 20th century, promoters of Wyoming recognized its richness in natural resources, and promised it as a rapidly advancing state developing new industrial opportunities. This was followed with the point that outside capital would be needed in large amounts, but they remained confident that the rich natural resources would draw this capital in. Oil was one of these resources, and the industry that formed around its extraction helped to create a relatively urban area in a notoriously underdeveloped state.

The high point of Wyoming’s oil production and refining took place in the early 1920’s. Casper was one of the main oil producing cities in Wyoming. It saw a huge boom between 1910 and 1925. Since there were so many jobs available, men from around the country brought their families and settled in Wyoming. The Midwest Oil Exchange, a penny stock exchange, existed on one side of Casper’s downtown. Its purpose was to intrigue investors so that money could be raised to buy equipment and lease land. In this same area there was an area known as the Sand Bar which also stimulated the economy in Casper. This area was less than reputable as compared to the oil industry but it did bring a lot of revenue to the town as a result of the increase of male workers. Sheepherders, oil refinery workers and Cowboys alike all flooded to the saloons, pool halls and prostitution houses that were found in the Sand Bar. Even after Wyoming became affected by Prohibition, they still generated profit, they simply became speakeasies and business went on as usual. Although Casper was known as Wyoming’s oil city, it was actually the Salt Creek oil patch to the North of Casper that was producing the largest amount of oil; not only in Wyoming but in the world at this time. This would greatly benefit veterans of the First World War as many men were looking for jobs and they found them in Wyoming.

The Salt Creek Oil Field of Natrona County was one of the major extraction centers in the state, producing roughly 3.5 million barrels of oil in 1923. This massive production fueled industry in nearby Casper, which held five refineries to process the massive amounts of oil coming out of Natrona County. Given Casper's relative proximity to the oil fields, Casper became a major hub for oil production, and this is well reflected in the census. Having a meager population of 883 in the year 1900, this population would more than triple to 2,639 by 1910, and then more than triple again to 11,447 by 1920 - making it the second largest city in the state. The sudden prosperity due to the oil fields, and the sheer reliance on them would result in Casper eventually being given the nickname "Oil City".

Though Casper was the largest example of urbanization due to the oil industry, many other places benefited greatly due to increasing petroleum demand and the state's natural ability to supply this demand. For example, the town of Lusk increased its population more than tenfold in the same 1900-1920 period. The University of Wyoming also found oil on its lands, allowing it to expand facilities despite an overall poor economic climate.

Demand for oil products, especially petroleum, came about as cars began to be introduced into Wyoming culture in years after the turn of the century. By the middle of the next decade, cars had become so widely used that the state began requiring licensing for the vehicles. Following this, Wyoming was motivated to focus on improving roads, eventually leading to the formation of associations to further these projects and accomplishing the creation of the Lincoln Highway. This would become the nation's "first designated transcontinental automobile route."

Perhaps the most important event that permanently changed Wyoming’s economic future was the Mineral Leasing Act of 1920. Since Wyoming was so rich in oil, the state began to do extremely well economically after this law had been passed. In the late 1920’s as the Depression was approaching, Wyoming oil companies saw a decrease in demand and the oil prices subsequently dropped. Many people at this time left in search of work elsewhere. It was not until the Second World War that the oil companies and the rest of America would be brought out of the depression. The high demand for oil from the Allied forces jump started the production of oil in Wyoming once more. American Aircraft Carriers, Ships, War Planes and Tanks were all in need of massive amounts of high octane fuel and Wyoming was able to produce it.

One of Wyoming's most notable events, the Teapot Dome scandal, comes out of this context of a state driven in its pursuit of expanding oil industry. The Teaport Dome Scandal also requires knowledge of another major factory that shaped Wyoming's economy, the Mineral Leasing Act. With the understanding provided of the impacts of the oil industry in Wyoming, we can look more closely at the changes brought by the implementation of the Mineral Leasing Act.

Mineral Leasing Act

[edit | edit source]The Mineral Leasing Act of 1920 altered the economic destiny of Wyoming. From the 1900s to World War I Wyoming’s economy was based on agriculture, especially cattle and crop production. However, as World War I came to a conclusion and the 1920’s rolled in, Wyoming transitioned into a time of unrest and economic uncertainty because of the depression. As persistent droughts and deflation of post war prices occurred, livestock and agricultural production fell. The value of meat and crop products dropped sharply. In 1919 cattle production was worth $42.00 but by 1925 cattle and sheep combined were worth only $26 million. In Fremon County, total crop value fell from $2.4 million in 1919 to less than $900 000 in 1924. Because of this decline, oil and gas became the new hot commodity. Wyoming State Geologist, Albert Barlett, stated that the “mineral industry was more important to the state economy than either livestock or agriculture”.

With the post war boom of automobile sales in the 1920’s and the need to supply the US Navy warship engines, petroleum was fast becoming an important new resource, rising from 13,000,000 barrels produced in 1918 to 44,000,000 in 1923. Wyoming, which sits on the most important oil fields in the Rocky Mountains, including the Teapot Dome, quickly became a large producer of the nation’s petroleum. However, this did not cushion the impact of the depression on Wyoming. The 1872 Mining Law allowed companies and corporations to own public lands in the west and to extract any minerals from them and retain all profits gained, by paying a very small fee. Initial discoveries of oil were generally kept as secretive as possible to prevent claim jumping, which was a chronic problem. Because of capitalistic desires, once word got out, each discovery prompted a scramble to claim and drill as much nearby land as possible and to produce as much oil as fast as possible. This often led to the draining of oil from neighboring tracts. This created a closed trading economy as the same few companies sold to each other, preventing any independent or smaller companies from entering the growing business. The New York Times wrote of the Standard Oil Company’s overwhelming monopoly of 99% of all oil production and transportation, and noted the impossibility of independent oil companies to compete in such a private system.

On February 25, 1920, the Mineral Leasing Law was passed by President Woodrow Wilson to combat the problems with the previous law. The law regulated the extraction of minerals to prevent resource monopolies and help stimulate the Wyoming's economy. It divided the legal status of oil, natural gas, coal and phosphates from minerals like gold, silver, copper and lead. It also restricted the areas of land and the length of time a company could mine resources from the area. It stated that a company could have no more than three leases in any state, never more than one in any given oil field, and the length of the leases were ten years. Most importantly, it placed the government in direct control of the land; now in charge of selling the leases and receiving one eighth of the profits made from the land. The act converted the federal government into a very large proprietor of petroleum lands. These restrictions helped the government control the formation of monopolies. Several Wyoming members of Congress were able to ensure that the federal government was required to pay back 37.5% royalties to state governments, thus helping Wyoming's economy greatly. Wyoming used this new capital gain to improve public schools, roads, and the University. The petroleum corporations praised the states new revenues, no doubt in an attempt to boost their falling status and popularity with the people of Wyoming who now had a chance to get out from under their boot.

Not everyone was in favor of this new leasing policy. Democratic and Republican citizens of Wyoming felt that it could take jobs away from Wyoming. And while in theory the plan initially prevented monopolization, price gouging and monopolization still occurred and depressed the oil and gas industry yet again. Production declined from the 1923 high to a low of 11,500,000 barrels in 1933. As the Great Depression deepened, so did the plummeting future of the oil industry in Wyoming.

Today these regulations have been increased so that the maximum federal oil and gas land that one can lease at one time is 246 080 acres. Wyoming royalties have also increased to today's 48%. Overall this law made exploring for and extracting oil and gas on federal and public land a privilege and not a right. The Mineral Leasing Act was essential in pushing the values of oil, gas, and coal in Wyoming beyond the values of agriculture and thus shaping modern Wyoming’s economy.

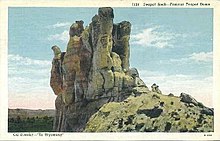

The Teapot Dome was a 9,481-acre oil reserve located 30 miles north of Casper and just south of Salt Creek in Wyoming. It was designated for the exclusive use of the United States Navy. Navy officials were concerned about the possibility of running out of petroleum, which their ships required to operate, so they created three oil reserves that were solely for their use the event of an emergency such as an oil shortage.

In the early 1920s President Harding transferred control of the Teapot Dome oil reserve from the department of the Navy to the Department of the Interior, which was run by Albert Fall. Fall proceeded to lease the reserve for the purpose of extracting oil to wealthy oil baron Henry Sinclair of the Mammoth oil company. Rumors of the leasing of the Teapot Dome oil reserves began circulating, which led Senator Kendrick, of Wyoming, to begin receiving letters and telegrams asking him to inquire about the rumored leasing of the reserves to private interests. Senator Kendrick proceeded to ask the Department of the Interior for information and was told that no contract for the lease had been made. Fall committed a lie of omission as he failed to announce that he leased the entire area of the Teapot Dome to Sinclair. Eight days after Fall replied to Kendrick, the Department of the Interior formally announced the leasing of the Teapot Dome. Fall had given the lease to Sinclair, owner of the Mammoth Oil Company. The government would receive royalties of 12.5-50% on the production of the oil wells in the Teapot Dome. There was an unusual provision on the lease that stated the government would not receive its royalty in oil or cash payments but in oil certificates. The certificates could be exchanged for fuel, oil, petroleum products or oil storage tanks.

Under pressure from various government members, the Senate voted to investigate the lease. Under the leadership of Senator Walsh of Montana, hearings began to determine first, why the land had been leased, and second, why there had not been competitive bidding for the reserve. Fall was called in for questioning but he continued to defend his leasing policy. Senator Walsh critically analyzed the lease, as well as past legislation relevant to the lease and questioned witnesses to determine whether the contract made with Sinclair was acceptable. Witnesses brought to light Fall's sudden increase in wealth, mentioning that he had substantially increased his fortune at the time he leased the Teapot Dome. Fall's alibi to the courts was that he had big business in mind and that he wanted to increase the wealth of the United States. Unbeknowst to the rest of the senate however was that he was profitting alone off of this endeavour. As he was going to lease this off it would go towards other gas or oil barons in order to lighten his trails. There was speculation that Sinclair had given Fall gifts and money in return for the Teapot Dome lease, but Sinclair vehemently denied this.

People argued for and against the lease. Those in support argued that the contract would allow Wyoming to expand their market for oil and in turn increase the price of the state’s crude. People opposed to the lease argued that the leasing process should have included competitive bidding and public knowledge. Governor Robert Carey and former Governor B.B. Brooks felt that the reserve should be left untapped while there was a national surplus of petroleum, as there was. In January of 1924, the Senate voted that the oil leases were illegal. Senator Kendrick declared that the government lost millions of dollars leasing the naval reserves in the manner they did. Sinclair's Mammoth Oil Company was sued by the Federal District Court and Sinclair was indicted by a grand jury in Washington for contempt of the Senate as he refused to cooperate with investigators. Although Federal district Judge T. Blake Kennedy upheld the lease, the Circuit Court of Appeals and the United States Supreme Court overturned the decision and in May 1929, Sinclair went to jail. Fall appeared before the Supreme Court in October of 1929 and was tried for defrauding the government, conspiracy for the purpose of fraudulently disposing of the Teapot Dome and accepting a bribe. Fall's acceptance of gifts and bribes was his undoing. He was found guilty of accepting a bribe and was sentenced to one year in prison and a $100,000 fine.

Prior to the Watergate Scandal in the 1970s under the presidency of Richard Nixon, this was one of the largest political scandals the United States was had gone through.

Women in Wyoming State Politics

[edit | edit source]

Wyoming has been nicknamed the "Equality State" because of the very progressive attitude of State policies towards women. Gaining the right to vote was a constant battle for women in the United States. At the turn of the twentieth century almost every state saw women’s rights movements mobilize to try to secure the vote for women and by 1869, the government of Wyoming had given women that right. This momentous occasion allowed for neighbouring states to follow Wyoming's example. The right to vote was not the only public policy that Wyoming pioneered for women's suffrage. Wyoming’s territorial legislature was the first government in the United States to grant a woman a position within the government. In 1894, Estelle Reel became the first woman to hold state office as Superintendent of Public Instruction.

Wyoming also broke the gender barrier which prevented women from becoming leaders in politics. In 1924, the state elected Nellie Tayloe Ross as the first female Governor in the United States.

Nellie Ross, wife of Governor William B. Ross, played an avid role in her husband’s political works as governor of the state of Wyoming. When her husband passed away in 1924 while still in office, there was call for a new election. The Democratic Party nominated Nellie to run and continue her husband’s term. On January 5th, 1925, Nellie Ross won the election and became the first female governor in the United States. She had defeated her opponent by over eight thousand votes and went on to direct the United States Mint in Washington and acted as a spokesperson for Women’s Rights. Nellie Ross has become a prominent figure in women’s movements across the United States for her ability to gain the respect of men and become the first female governor, not only for the state of Wyoming, but for the entire nation of America. The diverse politics of Wyoming has helped establish a state that has the ability to place gender roles aside and is accepting of females in politics. Since its establishment as an official state in America in 1890, Wyoming has diminished the barriers surrounding other states by allowing females to hold political office, and has officially become the Equality State.

Contributions to World War II

[edit | edit source]

Wyoming did not have a large presence in World War II, but nearly 10 percent of its population became soldiers. By the end of the war, 1,095 men from Wyoming had lost their lives. Prisoner of War (POW) camps were crucial installations throughout the United States and were created throughout the United States, although for the most part they were established in the southern states. Like many other States, Wyoming established these Camps, as well as Military Airfields. Wyoming's largest and most famous POW Camp was located in Douglas, Wyoming. At the height of the war, Camp Douglas held nearly 1,900 Italian prisoners and later, around 3,000 German prisoners. Along with the main camp in Douglas, there was another base camp in the city of Cheyenne, as well as smaller Branch camps all throughout Wyoming. Wyoming was also home to several Military Airfields that were established in order to train United States forces how to operate the fighters and bombers. Many of these Airfields have now been converted for public and commercial use. The most notable of these bases was the Francis E. Warren Air Base, which has remained one of Wyoming’s most historical sites. Unlike almost all other states, Wyoming did not attract war industries; however, the state’s resource industry, particularly coal, iron and oil thrived. Agriculture also assumed new importance based on a theory that “food will win the war!”

Japanese Internment

[edit | edit source]

In early 1941, the House Committee of un-American Activities had begun investigating the possibilities of Japanese espionage, but could not have predicted the Japanese surprise attack on Pearl Harbor that occurred on December 7 1941. On December 8th 1941, President Franklin Roosevelt declared war on Germany, Japan, and Italy thus entering the United States of America into World War II. Upon the country’s declaration of war, Wyoming began rounding up Japanese-Americans and immigrants and placing them into what was originally considered concentration camps until being renamed “internment” camps. Under the authority of the War Relocation Authority, the state of Wyoming arrested and interned these Japanese citizens. The "Nisei" individuals were Japanese Americans who were born in America. The "Issei" were Japanese immigrants who had clung on to their original customs and traditions. Finally the "Kibei" were Japanese-Americans who were born in America but who also went back and forth to Japan. To the American government none of these different subcultures had mattered as the country was under fear that anybody could be a spy for the Japanese government. These “interned” individuals were taken away from their homes and their possessions, placed in a secluded setting, which was set up similar to that of a small "community". Each "community" had its own hospital, education centre, and other necessities. Heart Mountain Relocation Center was located in Wyoming and was one of the main internment camps in the United states, holding 10,767 people at the peak of its population in 1943. The prominent difference between the internment camps and towns was that they were surrounded by barbed wire fences and did not allow anyone to leave. Following Executive Order 9066, American-Japanese citizens were to be jailed for no more than 4 years. The reasoning behind the arrest of these individuals was based solely on the fear caused by the attack on Pearl Harbor by their native country. Those Japanese-Americans who were studying in universities in other states, and those who managed to move to East-coast states, were able to dodge the internment because the fear was primarily on the West-coast. It should be noted that although they were not interned, they were not trusted by the American public, and thus were closely watched. In 1942 Japanese-Americans were designated as “undraftable because of ancestry”. However following January 20 1944 it was declared that for select service the Nisei were re-eligible to join the American war effort. As a whole this meant more freedom for the Japanese-Americans, and proper reintegration into civilization.