History of Western Theatre: 17th Century to Now/Scandinavian Pre-WWII

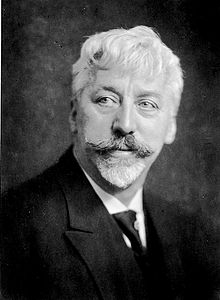

August Strindberg

[edit | edit source]

In addition to the plays from the late 19th century, major August Strindberg's plays in the 20th century include "Påsk" (Easter, 1901), "Dödsdansen" (The dance of death, parts 1 and 2, 1905), and "Spöksonaten" (The ghost sonata, 1908).

"Easter" "should be mentioned for the portrait of the young girl Eleonora, whose half-crazed, visionary utterances attain to a certain poetic level. Sanctimonious almost beyond belief is Strindberg’s tone in this story of Swedish bourgeois life at its dreariest" (Mortensen and Downs, 1949 p 134). Other critics find the family atmosphere more interesting. “We are shown in 'Easter' a family living under the shadow of disgrace, from the embezzlement of the funds of children and widows which have been entrusted to the father of the family. With restrained art of the most unobtrusive simplicity, the characters stand forth in chiselled distinctness- rich in homely virtues, patient, conscientious, energetic, but all narrowed by the cheap ideas of familiar convention, seeing heroes and heroines in each other and regarding their critics and creditors as the conventional demons and villains of popular melodrama. The mother is harassed with the obsession of loyalty- the self-induced conviction that her husband was innocent or at least that there must have been some flaw in the legal procedure which condemned him. Her son Elis, the young scholar, distrusts his friend and rival, frets over his lot in the most feebly womanish way, and lacks faith even in his betrothed, Christina, who tries to lift the depressing burden as best she may. Even little Benjamin, committed to the charge of the family because of the father's embezzlement of his property, is an indirect victim of the abnormal strain imparted to the family's vision- he fails at school in his examination...The little daughter Eleanora...is a psychic of marvellous powers of insight...Under the ministration of this gentle spirit, the illusions of convention vanish away; the scales fall from the eyes of all. The old gentleman- with his terrifying blue document- breaks down the false pride of Elis by forcing him, under threat of foreclosure, to do the right, however bitterly his conventional pride and false sense of dignity may protest. This, truly, is one of the most impressive dramas of suggestion ever written” (Henderson, 1913 pp 60-62). Elis “is brimming with an aggressive self-pity, with pride, with a coldness of soul that excludes the rest of the universe. He is solipsistic, taking every event in the neighborhood as having a meaning only for him…[Kristina] opposes his volatility with calmness...Eleanora, too, makes explicit the need for patience forbearance, acceptance self-denial...Both Eleanora and Lindkvist represent extremes of accommodation” (Freedman, 1967 pp 24-26). “Despite the warmth and affection she brings to the play at a time it is most needed, the possibility that she is mad is never denied” (Manheim, 2002 p 78). “The form...comprises the three acts of the Passion Play: the day of purification culminating in partaking of the flesh and blood at communion services, the long...Good Friday of suffering...and the evening before the resurrection with the promise...of hope...The nicely presented characters include a stubborn and arrogant adult son, a mother and wife who pretends she believes her husband imprisoned for forgery is innocent but really knows better, a sensitive young boy capable of riding above egotistic concern with self, a prospective daughter-in-law who is no longer a sleepwalker, an elderly man who knows the ways of the world but who has achieved both acceptance of humanity and resignation, and Eleonora, a teenager who is ‘a poetic figure of light in a world heavy with bitterness’” (Johnson, 1976 p 161). "In 'Easter', the most mystical of Strindberg’s plays, he draws an exquisite character of a young girl who is 'mad', whose soul is pure and lovely, and who sees and hears things that happen far away. To her, also, all secrets are open she can see the stars during the daytime, and, though her head is 'soft', her spirit dwells in the realms of pure beauty" (Lind-AF-Hageby, 1913 pp 296-297). "The play exemplifies [the] dream character. Kristina remarks that at times she has gone about as though in a dream. Eleonora also announces that she has been with her father who is in prison, and with her sister in America; with them in her sleep. We have, moreover, the characteristic of dream stressed by the frequent occurrence of the expression 'everything repeats itself". Eleonora attracts our attention more than the other characters. She would undoubtedly be declared insane by alienists. While there is nothing in her action that need be judged harshly, it is nevertheless clear that she is either 'beyond good and evil' or else lacking in concepts of both. Furthermore, as stated above, she is with her father and her sister while she is asleep, and she seems to have faith in her dream knowledge that her sister has sold a large quantity of goods in her shop. She also can sense when prison authorities are cruel to her father...Eleonora remarks further, apropos of time, that the clock in the house always went fast when misfortune was at hand but went slow when the house enjoyed good days. Likewise at the end of the play Eleonora tears off the calendar sheets in order to hasten the passing of time. For this girl, time and space do not exist and cannot exist. She is a creature of another plane" (Dahlström, 1930 pp 168-169).

In both parts of "The dance of death", we find “unforgettable characters: Edgar, the frustrated officer who becomes one of the living dead and a practicing vampire, Alice, the frustrated coquettish army wife who has almost sunk to the level of troll, Kurt, the friend who has achieved acceptance of humanity as well as resignation to other imperfections in living, Judith, a young woman who could become her father’s image but who also has the capacity to love, Allan, a sensitive young man who shows no signs yet of becoming a troll” (Johnson, 1976 p 163). "It is essentially due to Part I that 'The dance of death' ranks among the great Strindberg dramas. It is most of all a parallel to 'The father' (1887) not only because of its motif but also because it is a clearly naturalistic play in spite of its late date of composition. It is a depiction of marriage of a more somber intensity than any other of those Strindberg- or anyone else- has written for the stage" (Hildeman 1963, p 269). “Life, in a setting of diabolical ferocity and hideous struggle, is set nakedly before us- in two separate plays, the second but the shadow, the reflection of the first. We see the drama of existence played out before our stricken gaze- the terrible struggles for self-realization, arising out of inequalities in condition, incompatibility in temperament; the duel of sex, a duel to the death, because of the futile struggle to realize unity through diversity, the foreordained tragedy inevitable when one individual strives to attain supremacy through the frenzied effort to shatter the integrity of another's character" (Henderson, 1913 pp 68-69). "The figure of the captain of the fortress, the untruthful, scheming old rascal who has attained to a diabolical mastery in the art of making others unhappy and uncomfortable, is drawn with a supreme irony which makes it unique in vital drama. Amongst Strindberg's realistic plays it has another distinction: it represents his only stage-creation of a vampire-like husband. The wife is naturally not far behind him" (Lind-AF-Hageby, 1913 p 310). "The captain and his wife in 'The dance of death' have seen each other so long and so closely that they no longer see each other at all. They try, like all people, to find moral tags in the name of which they can justify their mutual hatred. It is a profoundly true circumstance that Alice does this more continually than her husband, who yields quite unreflectively to his vindictive impulses. The woman is more passionate, yet more desirous of justifying her hatred. Hence she is eager to prove to him the qualities that explain it. She has, no doubt, chances enough. Again and again she convinces her friend and kinsman, Curt. But in the end all hatred breaks down because all isolation of moral qualities becomes impossible. We know least those whom we know best, because we see them no longer analytically but concretely. We have no clues, because every clue becomes coarse and misleading when brought to the test of a reality so intricate and obscure. This husband and this wife feign, at times with passion and terror, to despise and hate each other. Yet they are unable to break their galling chains because, having passed beyond the perception of mere evil qualities in each other and seeing each other as concrete psychical organisms, they cannot hold either contempt or hatred long enough. They shift and waver and know too much to rise to the point of willing and they die in the inextricable bonds in which they are caught" (Lewisohn, 1922 pp 65-66). "At the last the husband dies, but the wife does not triumph as she sees him drop. She remembers him as he had come to her in his youth and strength, and it is the ardent and generous lover whom she sees. 'He was a good and noble man,' says the wife. And she realises that the life which she had hoped to enjoy when he was removed from her path can now never be. With his death, nothing is left to the wife. For hatred was her life" (Campbell, 1933 p 129). "This element of love-hate seems hardly to justify the use of the word 'love' when we read The Dance of Death, for it is hate that streams on and on through the drama. Yet there is a tiny fractional element of affection, if these two creatures are really capable of it. For some reason or other they have never been able to part from each other, though they quarreled as lovers and battled constantly throughout the twenty-five years of their marriage. Alice also recognizes that Edgar has had no easy path in life, that he has in fact constantly struggled against heavy odds.66 She has even found the man to be tender at times67 and she admits that he is really to be pitied. In the pantomime scene, the Captain shows tenderness for his children, and for the cat!" (Dahlström, 1930 pp 108-109). "This egotist and sadist dies fully convinced that he is righteous and has much to forgive his wife. She, who is also far from guiltless because she has provoked and betrayed him, strikes him and pulls his beard when his condition leaves him helpless. Hatred has bound them together as strongly as if they had loved each other, and their perverse relationship produces two of the most demonic characters of all literature" (Gasser, 1954 pp 391-392). “We might describe Captain Edgar as a megalomaniac suffering from an inferiority complex and persecution mania. His overweening arrogance, his contemptible bullying, his cringing towards superiors, his comfortable familiarity with subordinates- all these are touched off with a technical brilliance which not even Ibsen has exceeded. Nor has any master created any single figure approaching the malignity of Alice...tigress with the viper’s heart who, when her husband dies at the long last, has these words: ‘I’ll not act as undertaker to a rotting beast. Drain-men and dissectors may dispose of him. A garden bed would be too good for that barrowful of filth.' Yet both characters are touched to a kind of greatness” (Agate, 1944 pp 121-122).

"The characters of The Ghost Sonata are certainly a queer lot. The Old Man, Director Hummel, and the cook are vampires who seem like devastating dragons out of fairy lore. The Old Man is eighty years of age, but he has an infinitely long life behind him; and, from his interest in the destinies of all people, it would seem that time has had no place in his life. He is also a troll-man and has been everything...The Student, too, is an unusual figure. He is a Sunday child and is gifted with vision that children born on week-days never have. He sees the Milkmaid when she is invisible to the Old Man; likewise, he sees the Dead One, when the Old Man sees nothing; and, later, only the Student and the Old Man see the Milkmaid. The Student also considers the Young Lady beautiful, and the Old Man remarks that the Young Man sees what others cannot...[The] element of distortion also extends to the afternoon tea which is first described to us as a ghost supper. When the guests are finally assembled for this tea, the atmosphere is such that the social function becomes quite spectral. The whole play is, in fact, an excellent illustration of the principle of distortion. Things are distorted in order that we may get a closer view of truth subjectively" (Dahlström, 1930 pp 197-198). "The student speaks to the ghostly milkmaid in the most matter of fact fashion. Even the old mummy, the madwoman who always sits in a closet, talks like a most realistic parrot when she is not talking like a most realistic woman. Here it is the ideas that stagger and affright you, the molding minds, the walking dead, the cook who draws all the nourishment out of the food before she serves it, the terrible relations of young and old, all of them are things having faint patterns in actuality and raised by Strindberg to a horrible clarity" (Macgowan and Jones, 1920 pp 30-31). “In its cruel revelation of truth about a home by stripping it of all pretense and revealing the truth with its distortions, 'The ghost sonata' is a nightmare evoked by a creative observer” (Johnson, 1976 p 169). "The three compact scenes constitute a statement, a counterstatement, and a conclusion. In Scene I an Old Man, Strindberg alias Hummel, tells a youthful student about the long series of events which has brought him at last to a wheelchair, a spectator on the scene of life. We are prepared to view Hummel sympathetically throughout scene I and part way through scene II, for he is an effective advocate of his own cause, but when, after he strips another character, the colonel, morally naked, he is himself arraigned on the same charges, we are not surprised or disappointed that he hangs himself. Scene III is a dialogue between the student and a beautiful young lady. Will youth succeed where age failed? At first it seems as if this might be Strindberg's meaning. But the young couple soon realize that evil is much the same today as it was yesterday. Indeed the young lady dies as a tribute to this fact. The student recommends religious resignation, and the play ends. Such is the outline. It is filled in by Strindberg with enough matter for several plays. There are two 'eternal triangles', and an illegitimate daughter from each is among the characters. Strindberg links his personages by these and several other amorous episodes of a past which is dead but not at rest. As a character in another Strindberg play has it, 'Everything is dug up. Everything comes back.' Ghosts appear on the stage, and more formidable than the ghosts are the still living old people who are but ghosts of their former selves. The lover of Hummel is now a crazed old mummy who lives in a closet and thinks she is a parrot except when, with the lucid license of nightmare, she becomes sane in order to denounce her man. She is mocked by the presence of a statue of herself as she was in the days of her youth. Hummel's former fiancee is a white-haired old lady but, lest we form too ideal a conception of her, we learn that she was seduced by the colonel whom Hummel had cuckolded. The knots of legitimate and illegitimate relationship are tied and retied until we have a group of persons resembling a European royal family. The mummy comments: 'Crime and guilt bind us together.' The themes and situations are old Strindbergian 'idées fixes'. People have gone off on various journeys through life, yet they are tied to their past, to their actions, to the house where they were born. 'We have broken our bonds,' the mummy continues, 'and gone apart innumerable times but we are always drawn together again.' Guilt hangs in the air, and the crimes that lie behind it are- as ever- crimes of tyrannous possession, which Strindberg always represented in two metaphors: the vampire sucking the blood of his victim or the creditor using his power over the debtor" (Bentley, 1953 p 170-171). “In many or most of Strindberg’s plays one character has the faculty of seeing through everything; here it seems as though everything were seen through by everyone. In the words of the colonel, as quoted by the young lady: ‘What is the use of talking, when you can’t impose on each other?’ Even Strindberg could go no further along these lines” (Mortensen and Downs, 1949 p 143). "The final picture of The Ghost Sonata is Böcklin's picture of the Isle of the Dead described as follows: the island of the title is in the center of the canvas, with steep cliffs to the water on both sides. A grove of cypresses extending down to the water in the middle of the island forms a central core of darkness. On either side of the cypresses are cliffs with openings in them, generally considered to be burial vaults. In the lower center of the canvas is a small boat with a rower and a white coffin. A white clad figure stands in the boat facing the island" (Fraser, 1991 p 282). “The student learns in scene after scene, as more is disclosed, that the reality he believed in is in fact an illusion; and when he tries to speak his reality, it kills the girl whom he has loved” (Cima, 1993 p 75). "The student becomes initiated into human existence in The Ghost Sonata...The milkmaid is dead, yet the student can see her, whereas Hummel cannot. The milkmaid is dead because we are in the realm of the dead...It should be clear that in the play we are among the dead if for no other reason than the vanishing of the Hyacinth Room at the end and the appearance of Böcklin’s painting The Island of the Dead. No one has killed the student; he is already dead when the play begins, and his disappearance at the end confirms his death. The student experiences, in death, a process of initiation into human existence that he did not receive in life, since he died at such a young age...Paradoxically, he becomes initiated into human existence in death, when he passes through the three states of the Swedenborgian spiritual world...The milkmaid is an apparition whom the student can see because he is a Sunday child (the milkmaid stares at him in terror because he shouldn’t be able to see her), one who, according to Scandinavian folklore, can see supernatural phenomena and possesses the gifts of prophecy and healing, all because he was born on a Sunday. The student’s name is Arkenholz (literally, ark wood), which suggests the saving vessel of the Bible...He thinks he spent the night healing the wounded, but in fact he is dead. He died when the house collapsed; that is why the child he rescued from the building disappeared from his arms: being saved from death, the child remained in the natural world...Hummel cannot see the milkmaid early in scene 1 precisely because she has been dead for a long time and is an apparition...whereas he thinks that he is still alive. By the end of scene 1, as he becomes reconciled to his death and feels safe enough to mention the milkmaid to the student and lie about what happened to her, he can see her...The mistake Hummel makes, in attempting to take over state number two, to possess the apartment building, is in thinking that he can expose others without being exposed himself...In state number two, to elaborate on Swedenborg’s description of it, the human spirits can no longer hide their thoughts...Paradoxically, and triumphantly, it is the mummy who leads the way in the exposure of Hummel. Her horrifying mummified condition is her true self: dead to the feelings of others, withered spiritually...Scene 3, which takes place in the Hyacinth Room, represents the third state of man after death, 'a place of instruction and preparation for those who may merit a place in heaven' (Sprinchorn, 1978: 379). What the student learns here, and what the young lady already seems to know, is that their union, as planned by Hummel, is impossible now except in heaven...The young lady is a creature of this world who has long since been initiated into the everyday drudgeries of human existence, the struggle to survive from day to day. She feels that she experiences the drudgeries of life all the more acutely in her home as a punishment for the sins of her family; she is trapped and guesses that 'this is how it’s supposed to be'. The young lady is a victim who seems not to have sinned egregiously herself, but who has accepted or endured the sins, the imperfections, of others. She is a proponent of the secular salvation that the student ultimately rejects, of patience, gentleness, and compassion as the answer to the problems of this life: that is why, throughout scene 3, she keeps telling the student to wait. He desires union with her; she knows that there can be no heaven on earth, no spiritual salvation, finally, in secular salvation. The student has rejected this life for life in the hereafter; the young lady, however, has not" (Cardullo, 2016 pp 288-293).

"Easter"

[edit | edit source]

Time: 1900s. Place: Sweden.

Text at http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/8500

Elis and Kristina intend to marry in the fall and, after passing through a rough winter, look forward to summer. One year has passed since his father was imprisoned for debt, the principal creditor being Lindkvist. Soon after, Elis' sister, Eleonora, went insane and was sent to an asylum. On Maundy Thursday, Kristina is surprised to learn that Elis wants to attend a dinner given by an ungrateful student of his, Peter, who stole some of his ideas in his doctoral thesis. They receive an anonymous package containing a birch rod, which Elis, instead of taking the presumed threat badly, places in water. A grief-stricken Benjamin, a pupil living in the same house, informs them that he has just failed his Latin examination. Looking out the window, Elis notices Lindkvist, who may soon decide to take away their furniture, but the man merely nods, smiles, and passes by. Left alone, Benjamin is surprised to find a stranger entering. It is Eleonora, escaped from the asylum to join her family. She informs Benjamin that her father was arrested because he took the blame when she embezzled some funds. She suffers for his sake and all her family. "Will you be one of my flock, so that I can suffer for you, too?" she asks. She hears the telephone wires hum, caused by the cruel words people say to each other. She also tells him that she just entered a florist's shop and took away an Easter lily, which she places on the table. Elis learns his father's case has been sent to the court of appeals, so that he must read the court transcripts to find a loophole in the procedure. He notices the Easter lily. "Poor Eleonora," he exclaims, "so unhappy herself yet bringing joy to others!" On Good Friday, Elis is unable to discover any loophole. He and Kristana find comfort in looking at Benjamin and Eleonora's love grow, who push the lamp towards each other so that they can read more easily. Elis' mother, Mrs Heyst, informs them that Lindkvist is about to come over, a thing which greatly worries them. She also tells them a burglary was committed at a florist's shop. They anxiously behold Lindkvist's shadow on the curtains, enlarging to a giant-like size, but he goes away. "Think of it as a trial, Elis," Kristina advises. When the rest go, Benjamin suggests to Eleonora to call the florist' shop and explain the mistake. "No, I have committed a wrong and I must be punished by my conscience," she answers. "Everyone must suffer on Good Friday, to be reminded of Christ's suffering on the cross." On Easter eve, Elis worries that Kristina has left him. He learns from his mother that the Easter lily was stolen, at which Benjamin blames himself until Eleanor admits her mistake. Then Mrs Heyst says she spoke to the florist, who finally found a coin Eleanor put there. Lindkvist finally arrives. "I ask neither charity not favors, only justice," Elis proudly declares. Lindkvist accedes to this point of view, demanding him to pay back all that he owes and warning him that, unless he begs the governor's help, he will arrange to have his mother arraigned as well. Elis is forced to accept all his conditions. Lindkvist next informs Elis that he must thank Peter for interceding on his mother's behalf to the governor, which he declines to accept. To "squeeze his pride", Lindkvist next demands the crushed man to empty his bank account and give over the entire sum to him. But then the apparent monster reveals he once knew a man who long ago saved him from prison, when he was falsely blamed for breaking a window-pane: Elis' father, and so, for his sake, he cancels all his claims. A stunned Elis watches Eleanora tear the leaves out of the calendar and exclaim: "April, May, June, and the sun shining on them all!" as Kristina walks back in to join her husband.

"The dance of death, part 1"

[edit | edit source]

Time: 1900s. Place: Sweden.

In a fortress tower of a military camp, Edgar and Alice are near their silver wedding anniversary. Because of Alice's coldness and brusque manner, a servant, Jenny, quickly leaves them. Instead of supplying his usual remark to her usual remark, Edgar yawns. "What else is there for me to do?" he asks. Another servant, Kristin, is hired but may follow the other one. "So now I am the domestic again," an upset Alice complains. The unhappily married pair receives the visit of Kurt, her cousin and the new master at the quarantine station. Edgar and Alice agree on one point at least: they dislike everyone on the island. "I have had nothing but enemies all my life, and instead of being a hindrance, they have been a help to me," Edgar rejoices in saying. Suddenly, Edgar becomes motionless, the victim of a stroke. Yet almost immediately after his fit, he goes out to inspect the guard. Left alone together, Alice informs Kurt that her husband incited their children against her, as she did. She bemoans the state of her hands because of domestic duties, resenting having lost a career as an actress following her marriage. Edgar returns but almost as soon collapses under the throes of a second stroke. After learning he is still alive, Alice sighs with sadness, but sobs after learning Kristin has abandoned as the previous servant. Alice and Kurt learn by telegraph that none of the doctors can come to help Edgar. "That's what you get for treating your doctors so contemptuously and always ignoring their bills," she accuses Edgar. He denies this. While the captain stares emptily into space, Kurt informs Alice that a doctor said he may die at any moment without warning. She is heartily glad about that piece of news. But, after a night of rest, he recovers. Alice tells Kurt that it is thanks to Edgar that Kurt's wife obtained custody of his children. According to Alice, it is Edgar's vampire nature that expresses itself when he tells Kurt that his son, a cadet officer, will be transferred to the island, which Kurt disapproves of. Edgar next tears up the will in his wife's favor and declares he has filed for divorce. Alice is glad of this. She accuses him of once trying to drown her but without witnesses, the captain notes, except for their daughter, Judith, a daughter whom he taught to lie, Alice accuses. "I didn't have to," he remarks. Free at last from the marriage bond, Alice begins to flirt with her cousin and playfully bites his neck. In anger at the sudden pain, he raises his hand to her, but she forces him to kiss her shoe. They eventually discover that Edgar heard no word about Kurt's son's transfer and never filed for divorce. Although Alice is willing to follow Kurt wherever he goes, he pulls away from her, so that the unhappily married couple are back together again but beg Kurt to remain. Throughout it all, the captain has one piece of philosophy which never fails to sustain him: "Erase, and keep going."

"The dance of death, part 2"

[edit | edit source]

Time: 1900s. Place: Sweden.

Kurt has noticed that some of his supposed friends have grown colder towards him, a sign, according to Alice, that Edgar has been stealing these friends from him. Edgar accuses Kurt of ingratitude in view of the 6% profit he gained while investing in a soda water company on the basis of his advice. In love with Judith, daughter to Edgar and Alice, Kurt's son, Allan, a cadet officer, is reduced to tears, tormented by her indifference towards him. Alice advises Allan to compare notes on her with his rival, a lieutenant, because the real objective of her ambition is neither of them but a colonel, despite his sixty years of age. Later, Edgar informs Kurt that the soda water company he invested in is now out of business. Without informing his wife's cousin, Edgar sold his stock before the crash. As a result, Kurt loses his savings and is forced to sell his house and furniture. Edgar advises him to send his son away to a cheaper school, since he, too, wishes Judith to marry the colonel. Moreover, he takes over Kurt's house and furnishings and tells Allan he is transferred to another training course. When Allan discloses to Judith he will be away for a year, she says she will wait for him. When Edgar informs Kurt about the transfer, paid for by a group of military men, Kurt is crushed, for this amounts to charity, which ends his hopes of being elected in parliament. Edgar is surprised Kurt ever considered this, especially on considering that he intends to run for the same office. "This indicates that you underrate me," Edgar accuses him. Has he anything to reproach him with? No. "You say this with a resignation I should like to call cynical," Edgar comments. However, Edgar's marriage plan concerning Judith is thwarted when he learns in a telegram from the colonel that she recently insulted him and so he is no longer interested, after which Edgar suffers another stroke. "Look after my children," he pathetically cries out to Kurt. "This is precious," Kurt remarks, "he wants me to look after his children after stealing mine." On seeing Edgar's prostrate state, Alice gloats. "Where is that strength of yours- your own strength- now?" she asks with irony. Pushed to the limit, he spits on her face. In turn, she slaps his and pulls at his beard. Distressed, Kurt and the lieutenant charitably carry him to bed. The latter soon returns to reveal to Alice that her husband is dead. "I have a feeling my own life is now at an end, that I'm on the road to decay and dissolution," she wrily comments.

"The ghost sonata"

[edit | edit source]

Time: 1900s. Place: Sweden.

Text at http://www.archive.org/details/playcriticalanth00bent https://www.gutenberg.org/files/44302/44302-h/44302-h.htm https://pdfcoffee.com/the-ghost-sonata-pdf-free.html

Arkenholz, a student, wanders in a street after being up all night to help save people from a house fire. Because his eyes are inflamed and his hands are possibly infected, he asks a milkmaid to put a damp cloth on them. Director Hummel, an old rich man bound in a wheelchair, asks Arkenholz to whom he has been speaking and is startled to hear of the milkmaid's existence, whom he does not see, a woman he once had sexual relations with and then abandoned. They discover that Hummel knew Arkenholz' father. According to the father, Hummel once cheated him in business dealings, but the latter denies it. On the contrary, Hummel helped him to such an extent that the father grew to dislike his benefactor. Nevertheless, to help along Arkenholz's career, Hummel proposes to give him a ticket at the opera where he is to meet influential people, notably the colonel and his daughter, to which the student agrees. The student described how he saved a child from a burning death last night, but as he was about to take hold of him, the child disappeared. As they speak, a dead counselor in his shroud appears in the doorway of a house and goes away, then is seen a second time by the student but not by Hummel. In the colonel's apartment, Bengtsson, his servant, describes to Johansson, Hummel's servant, the forthcoming evening as a "supper of specters", when the colonel either talks to himself alone or the others repeat over and over again the same matters. He presents the colonel's wife, Amalia, surnamed "The Mummy", demented, it appears, living in a wardrobe and imitating a parrot's voice. When Hummel arrives, he is startled to see her, a woman with whom he had adulterous relations and the undivulged father of her daughter. For unknown reasons relating to an unhappy marriage, Amalia is only pretending to be demented. Hummel confronts the colonel by telling him he has bought the bills of all his debts. Hummel also reveals that the colonel's aristocratic title is false and that the colonel's daughter is his. In addition, he wants the colonel to turn out Bengtsson, his intention being to reveal the crimes of others. But the mummy reveals Hummel's own crimes, calling him a "man-robber", how he cheated her with false promises, hounded the counselor to death with debts, manipulated Arkenholz under the pretense that his father owed him money, and cheated Bengtsson while living off him for two years. Assailed thus, Hummel is reduced to squawking like a parrot and then quickly dies. After Hummel's funeral, Arkenholz and the colonel's daughter discuss her house affairs. She reveals her servitude to her own servants, how the cook sucks the marrow of the food she prepares, how she is forced to work at tasks her housemaid refuses to do. But when Arkenholz wants to take her away from this unhealthy environment, she recognizes the futility of this expedient, specifying that she is "struck at the very source of life". As if her body agrees with what she said, she quickly sickens and appears to be dying. Suddenly, the room vanishes and Böcklin's picture of the "Isle of the dead" appears.

Hjalmar Bergman

[edit | edit source]

Also of interest among Swedish dramatists is Hjalmar Bergman (1883-1931) with "Swedenhielms" (1925), detailing the relations between a physicist and his family, along with “Sagan” (The saga, 1919, first produced in 1942), detailing the relations between a young lover and his family. The plot of “The saga” resembles that of Musset’s “No trifling with love” (1834).

"Swedenhielms" "pictures a Swedish scientist and his family as he is awarded the prize at a time of personal and financial crisis; it is notable for its blend of fantastic satire and more profound implications, and for the validity of its varied characterization” (Naeseth, 1952 p 293). "The financial scandal serves in the end to reunite it. The love affair of the young ones is only briefly and quite harmlessly affected by the financial problem" (Sprinchorn, 1967 p 124). "Swedenhielms is a fine play, skillfully motivated, and nicely balanced with the elements of comedy and profundity" (Hilen, 1952 p 26).

In "The saga", “Rose is going to marry Sune for money, while she is already deceiving him with her true love and childhood sweetheart. The childhood sweetheart cannot marry Rose because his uncle forbids him. Sune loves Astrid but, urged by his father to be sensible and banish romantic notions, he will marry Rose. Everybody will end unhappy. Whether these people try to secure happiness by being cautious and intelligent or by being romantic and carefree, they seem unable to escape the fate The Saga predicts for them. However, even she is surprised by a new twist. Expecting the union of true lovers in death as in her own story, she is disenchanted by the sudden physical passion that flares up in the greenhouse between Rose and Sune at the very end. Thus, even love, with its bitter aspect, serves to bring together the two and puts its seal on the marriage of convenience. In spite of little ironies like this, however, the characters remain less the pawns of the irrational than the pawns of the one man who is responsible for bringing some of them together while separating the others: the local board of trade who is both Sune's father and the childhood sweetheart's uncle” (Sprinchorn, 1961 pp 121-122).

“As a dramatist, Bergman's place is secure. Bergman's plays are distinguished not only by the versatility and virtuosity of their dramatic technique but also by the broad and humane vision embodied in them...Bergman displays his dramatic facility in a variety of forms, and his plays gain their vitality from the presence of characters who are, if not necessarily of flesh and blood, intensely real. Like Strindberg, Hjalmar Bergman is both a self-explorer and an explorer of the self, a master of self-analysis and a great observer of mankind's follies and foibles. He too is particularly talented in the art of unmasking, but unlike Strindberg, he is essentially a comic writer. Bergman's comic vision is, however, of the contemporary brand: his humor is often black, and the mixed genre of tragicomedy best encapsules his image of man. Compared to the heroes we encounter in the classic comedies of a Holberg or a Molière, Bergman's characters are neither fools nor madmen but grotesque” (Johannesson, 1969 p 209).

"Swedenhielms"

[edit | edit source]

Time: 1920s. Place: Sweden.

Text at ?

Rolf Swedenhielms junior, an engineer, and his brother Bo, a lieutenant in the army, reveal to their sister, Julia, that, according to newspaper accounts and despite his accomplishments, their father is unlikely to win the Nobel prize in physics. Unaware of those rumors, a newspaper reporter, Pederson, shows up to interview Rolf senior but is greeted instead by Rolf junior. The family worry after receiving a letter from their father, Julia even thinking that a turn of phrase of his may mean he intends to commit suicide. However, despite financial troubles, Swedenhielm shows up with a countenance full of careless defiance. Uncomfortable because of a lack of funds, Bo wishes to discontinue his amorous relation with Astrid, a rich woman who loves him and does not mind to pay his way. Swedenhielm attempts to intervene. "You do not place a high value on his honor," he points out to her. "Then I'll marry you instead," responds the teasing Astrid, sitting on his knee. Unexpectedly, Swedenhielm wins the Nobel prize after all. He receives the visit of his foster-brother, Eriksson, a money lender who forty years ago was convicted to a two-year jail sentence for robbery. Marta, Swedenhielm's sister-in-law by his dead wife, reveals to Astrid that Eriksson has bought all the promissory notes of other money lenders on the debts incurred by the two extravagant sons. With his financial situation improved because of the prize, Bo approaches Astrid with renewed confidence, but now she turns away from him. Armed with the promissory notes, Eriksson revisits Swedenhielm to reveal his story of long ago, how he begged Swedenhielm's father, mayor of the town, to hush the matter up. Eriksson's mother also begged the mayor's wife to intervene, all to no avail. Eriksson shows Swedenhielm that on one of the debt papers he carries, the upper edge containing the lieutenant's monogram was cut off and on another that the signature appeared simply as Rolf Swedenhielm, not Rolf Swedenhielm junior, meaning that either son may be accused of fraud. Nevertheless, Swedenhielm accepts to pay his sons' debts. On the night of the Nobel prize, Swedenhielm appears glum. Exasperated by Bo's talk, Swedenhielm strikes his face and asks him whether he indeed forged his name. Though thinking it is his brother's work, Bo says yes. Marta intervenes to say she is responsible, not his sons, for without her borrowing, the entire household would have crumbled. After all that time, Swedenhielm at last thanks her.

”The saga”

[edit | edit source]Time: 1910s. Place: Sweden.

Text at ?

Heir to a fortune, Sune presents Rose, his fiancée, details of the castle they should soon be living in together, including a well where they discover Astrid, a friend of the family. Sune requests Astrid to recite Gudrun’s saga, but she declines. Having often heard it, Sune himself tells the story of his ancestor, a knight who built the castle and wished to rid himself of a troublesome girl in love with him. For this purpose, the knight approached her from behind to drown her in the fountain. Fearing that he would be guilty of a mortal sin, she put her head underwater till she died. Rose disbelieves that anyone would do such a thing. Sune is affronted. Their quarrel is interrupted by the arrival of Rose’s mother, a colonel’s wife, along with a counselor, Sune’s uncle. When asked by Rose whether Gudrun’s saga is probable, the counselor answers that Gerard, his nephew, a medical doctor, and Rose’s childhood friend, might know. Gerard considers the story improbable in current times. But yet the story reminds him of a patient suffering from depression who once stole a vial of morphine from his office. In anguish at his negligence, he was soon relieved to receive a letter of invitation to her marriage. Alone with the lovers and thinking that she may have swallowed morphine, Gerard is anguished at seeing Rose stoop languidly over a table. But after examining her, he asks Sune to fetch some wine. Sune rushes out. “You set up a trap for me,” Gerard accuses her. As Sune hurries back, he discovers Gerard and Rose embracing each other. In the midst of a party, Sune decides to rid himself of Rose but to put the blame on himself, and so he consults a notary for the purpose of handing over his castle and grounds to her. But yet unwilling to state the actual reason, he is at a loss to find a false one. Astrid suggests that he kill himself with the poison contained in her medallion, but is relieved to find that he declines the offer. He finally discovers a plausible reason: Astrid herself, whom everyone knows is in love with him. She accepts to be found out with her arms around his neck as the counselor, the colonel’s wife, Sune’s aunt, Flora, and the counselor’s brother, a gentleman of the chamber, enter together. When Sune announces his wish to break up his engagement to Rose, the counselor demands to know the reason. To everyone’s distress, Sune falteringly mentions Rose and Gerard until Astrid interjects that the reason is her love of Sune. The family is relieved that Rose and Gerard are accused of no wrongdoing. But when Sune states his donation to Rose, the counselor, doubting his sanity, tears up the contract. The gentleman of the chamber approves, as such a contract would blot the honor of the family. When Sune confronts Gerard alone, the latter defends himself. “It was an adieu to a childhood love,” Gerard declares, “to the dreams of youth.” As Sune seeks to find Rose, one of the party guests hands over Astrid’s medallion, which Sune is stunned to find empty. To obtain the medical point of view, the counselor requests Gerard to examine Sune, accompanied by a notary to obtain the legal point of view. Unable to find Astrid and fearing suicide, Sune blames his family for her woes, while the colonel’s wife and Flora blame Astrid for countering their designs. “Murder is against against the fifth commandment, perjury against the eighth, and adultery against the sixth,” Sune accuses, “but it suffices to call robbery a wise calculation, perjury a sanctified means for superior designs, forbidden love a game to laugh at, and old Moses can hide his law tables under his white beard.” When Sune enjoins Rose to join her family, she confesses she has none and has the impression of feeling a hand on her neck. Nevertheless, Sune pushes her away as cries are heard that Astrid has been spotted walking across the grounds. As Sune and Rose look for her separately, she reports to have seen Astrid from a distance, whereas he is unsure whether he has. As dawn breaks, Sune and Rose are seen together while Astrid sinks to the ground before the fixed dull stare of Gerard.

Hjalmar Söderberg

[edit | edit source]

A third Swedish dramatist of interest is Hjalmar Söderberg (1869-1941) with "Gertrud" (1906).

“An author targeted by the association for his erotic narratives was Hjalmar Söderberg, in the Nordic countries most famous for his novels and the highly controversial play Gertrud (1906), which depicts a married woman and her relationships with three men. Söderberg was critical of what he saw as the hypocrisy of bourgeois marriage, and used this as a recurring motif in his writing. With one sentence in Gertrud, which has become one of the most famous phrases in Swedish literature, Söderberg came to epitomize everything that the association thought was wrong with the new decadent literature: ‘I believe in the lust of the flesh and the incurable isolation of the soul’ (Johansson, 2020 p 176).

“The study of the composition...reinforces the impression that the main purpose of the plot is not to give Gertrud and her former lover, Gabriel Lidman, an opportunity to exchange aphorisms about love but to describe how she is overcome by her unyielding eroticism, debased by her relationship with an unworthy man and how she is eventually driven into loneliness” (Hasselmo, 1963 p 253).

"Gertrud"

[edit | edit source]

Time: 1900s. Place: Stockholm, Sweden.

Text at ?

After six years of marriage, Gertrud wants to divorce Gustav, a lawyer in line to become a minister in the next government. She wants to take up her singing career again. When Gustav assures her he still loves her, Gertrud is convinced he does. "Just like you love your Havana cigars," she adds. He suspects she has a lover, but she refuses to reveal who it is. It is Erland, a little-known but young classical music composer. Frustrated because they have not yet slept together, Erland says he wants to break off their relation and spend the night with Constance, a courtesan. After announcing her intention to divorce, Gertrud proposes that they go to his apartment. The following day, at a party given in honor of a famous but disillusioned and cynical dramatist, Gabriel, Gertrud's former lover before her marriage, Gustav discovers she has recently slept with another man and begins to resist more actively to the matter of her divorce. "Gertrud, this night you will belong to me one last time," he says. "Afterwards, you may go wherever you wish, to sink in mud and shame, since you want to sink." She leaves him without a word and meets Gabriel, who reveals that he met Erland the previous night at Constance's house, drunk and boasting amid the whores about his latest female conquest. When Gabriel asks her why she left him, she remains silent. As Gabriel wanders away, she accepts Erland's invitation to accompany her singing at the piano. She starts to sing Schumann's "Love and a woman's life" then faints. The next day, when Gertrud meets Erland in a public park, he mentions he does not see the necessity of her divorcing, but she nevertheless wishes to leave the city with him. He says he has no money. She counters that they may use hers at first and then together make money with their music. His pride will not permit that. Without imagining to give offense, he casually mentions going to Constance's house after having some trouble sleeping. He then reveals he cannot leave because of a secret engagement to a woman whom he does not love but cannot abandon while she is pregnant, one, moreover, who once helped him financially. Returning home, she meets Gabriel, who proposes that they go off together, but she declines. She left him years ago because love to him was an obstacle to writing, gaining fame, and making money. Now she wants to live alone.

Kjeld Abell

[edit | edit source]Danish drama is capably represented by Kjeld Abell (1901-1961), author of "Melodien der blev væk" (The melody that got lost, 1935) and "Anna Sophie Hedvig" (1939).

In "The melody that got lost", "the laborer whom Edith met in a long, colorful speech severely criticizes the political indifference of the middle class. This speech gives the first adumbration of a theme which Abell was to develop further in a group of plays from the late 1930s and the 1940s. 'Do you give a damn about us?' the laborer angrily exclaims. 'Not on your life! You and your husband rush into the cream-colored washstand and close the door every time there is trouble afoot- and in the meantime we others may lie around croaking on the front pages of the newspapers, in bold print and with pictures of the bereaved mourners- what kind of a pedestal is it that you have climbed up on?' The laborer's indictment of middle-class political apathy clearly reflects the troubled economic situation of the early 1930s with unemployment, strikes, and lock-outs" (Madsen, 1961 p 129).

In "Anna Sophie Hedvig", “Kjeld Abell deals with the murderer-psychology and the moral convictions of an old school-mistress in a masterly shifting and changing drama (Stensland, 1947 p 155). The "ringing indictment of the passive tolerance of evil was couched in the story of a quiet spinster schoolteacher who kills to defend her small world against the destructive tyranny of a vicious school principal” (Marker and Marker, 1975 p 241). “Anna Sophie Hedwig, an apparently colorless provincial schoolteacher who gives her name to the play, is undoubtedly intended to be a personification of the humble Danish folk who must kill their tyrant even though they are martyred for their deed. But on the surface, the play is mainly a realistic study with symbolic overtones of a bourgeois family roused from their petty self-absorption by the brave deed of the apparently insignificant country cousin” (Smith, 1945 p 304). "The middle-aged, mousy-looking schoolteacher who has the courage to destroy a local despot when she feels her little world threatened is Kjeld Abell's most impressive embodiment of the spirit of resistance...The family into which Anna Sophie arrive is not even 'all right'; it is completely indifferent to the outside world...The son, John, however, is an exception...John strongly defends her right to kill...By our passivity and political indifference we are all, in other words, responsible for the rise of dictators" (Madsen, 1961 pp 130-131).

Abell's “characters...protest against social, political, and spiritual evils, e.g. Edith (The Melody That Got Lost) rebels against the domination of her parents and society which have robbed her husband of all vitality; Anne Sophie Hedvig, in defending her little world in the schoolhouse, presents an example for all who are suppressed by tyranny of any kind” (Hye, 1991 pp 39-40).

"The melody that got lost"

[edit | edit source]Time: 1930s. Place: Denmark.

Text at ?

"Anna Sophie Hedvig"

[edit | edit source]Time: 1930s. Place: Denmark.

Text at ?

Anna Sophie has taken a leave of absence from her teacher's position at a girls' school and been invited at her cousin's house. Anna Sophie explains that her colleague, Mrs Möller, was to have been the principal of the school but was accidently killed and replaced by Miss Smith. Later in the day, the cousin's daughter, Esther, tells her brother, John, that the family dog has slipped its leash and cannot be found. Shortly after, the family receives the following telegram: "Has been found, all well, Esther". John laughs at the cryptic message, explaining that his sister has found the dog, but when Esther returns, she reveals she did not send that message. The message was meant for Anna Sophie, who explains that Esther refers to one of her pupils. The master of the house invites directors Hoff and Karmach for dinner when conversation turns on the subject of murder. "Is there any among us who could kill?" Hoff queries. To everyone's surprise, Anna Sophie confesses she not only could but did. She admits to having killed Mrs Möller so that Miss Smith may become the new principal. The night of the murder, the janitor of the school, Victor, was conversing with his wife when they heard a scream. He discovered Mrs Möller dead at the bottom of the slippery stairs he has just washed and concluded she must have stumbled. However, the police officer, Birk, suspects murder. He found the outside key in the victim's hand though she had rung the bell. He also discovers Miss Smith's handbag with her own key in it and so concludes that the murderer used Mrs Möller's key to enter the building. Moreover, the dead woman has black gloves next to her though she always wore grey ones. When the officer leaves with the couple, Anna Sophie returns to remove the gloves she inadvertently left on the murder scene. Unexpectedly, Esther enters. Her teacher explains that she knows about the letter the student sent to Mrs Möller concerning her bohemian behaviors. "She showed it to me," Anna Sophie says. "She wanted to strike at you but foremost at Miss Smith." Anna Sophie knew that an indulgent Miss Smith would defend Esther and so lose her chance at being principal. And so Anna Sophie stole Mrs Möller's key, murdered her, and now wants to give herself up to the authorities. A shocked Esther encourages her rather to save herself. At the dinner party, Anna Sophie explains that the telegram refers to finding Esther's letter. The family is aghast at her deed, but John defends it and attacks Hoff after heated words are exchanged. The lights suddenly go off in the room and the entire group moves outside. Karmach explains to John that his fight with Hoff has seriously harmed his father, who needed Hoff to relieve his financial difficulties. Not taking this into account, John accuses his father of neglecting his upbringing. "You gave me slackness, indifference, softness..." he specifies, at which the irate father throws him out of the house. Stunned at these events, his wife leaves him to follow her son while Anna Sophie is led to prison to be executed.

Hjalmar Bergstrøm

[edit | edit source]A second Danish playwright deserving mention is Hjalmar Bergstrøm (1868-1914) for his workplace drama, “Lynggaard & Co” (1905).

"Lynggaard & Co"

[edit | edit source]

Time: 1900s. Place: Denmark.

Text at https://archive.org/details/twoplaysbyhjalm00cogoog https://archive.org/details/cu31924026301923 https://archive.org/details/twoplaysbyhjalm00cogoog

Lacking confidence in Jacob, his son and heir, Peter Lynggaard intends to transform his distillery into a stock company with the help of his manager, George Hymann. But Peter’s devout wife, Harriet, resents George’s presence for refusing to take back one of the lead workers, Olsen, after their defeat in a strike ten years ago. She informs her father, Mikkelsen, that she has called back Jacob from Italy to prevent her husband’s plan of forming the stock company for being against the workers’ interest. Through the years, she has also been helping out Olsen’s widow with money. Mrs Olsen announces that her son, Edward, has finished serving a two-year sentence for counterfeiting. Taking the part of his son-in-law, Mikkelsen reveals to George the imminent arrival of Jacob. George announces to Peter that they must meet the under-secretary in charge of forming the stock company on this very day at 4:30 after meeting the workers to prevent a strike for higher wages. Jacob’s talk with Mikkelsen confirms his mother’s viewpoint: he wants to reorganize his father’s company more to the workers’ advantage. Jacob meets Edward, his old school-chum, who informs him that George refused him a position in the company. Feeling guilty about the past, Jacob promises him one, although the latter swears to avenge his father and adumbrates farfetched plans of toppling capitalism by making gold. Peter tells Mikkelsen that George has suggested their accepting the workers’ demands, thereby preventing the matter from interfering with the plan to form the stock company. Their rivals, Consolidated Distilleries, has been overproducing in view of fomenting the strike. Jacob confronts his father by requesting that everything remains as they are until he has formed his own plan for the company. But Peter dismisses his son by saying the company will be organized in his fashion this very afternoon. A distraught Jacob challenges his father by offering him to choose between George or him. “I’ll rather go childless to my grave,” Peter retorts, “than witness the destruction of the business inherited by my ancestors.” Meanwhile, Edward has changed his mind about his position. He now wants to refuse it because of bigger though unformed plans in the works. Since Harriet sides with her son by threatening to leave him, Peter confers with his father-in-law about what to do. Rather than put the company at risk, Mikkelsen advises him to let his daughter go for the moment along with his granddaughter, Estrid, secretly suspecting that the girl loves George and may further complicate matters. Indeed, she and George secretly become engaged to be married. Harriet brings the business matter to a head by demanding that the planned protocol be burnt. At last Peter yields. A disappointed George quits, in view of having received an offer from Consolidated Distilleries for a manager’s position without revealing his agreement to Estrid. The strike being imminent, Jacob meets with the workers but to his great disappointment is hissed at and repulsed. Aware of Astrid’s feelings towards George, Mikkelsen proposes that she ask him to come back. She refuses but admits to be engaged to him. “Now, children, you see how you have misjudged him,” Mikkelsen declares, the manager not having used his position as a future son-in-law in his business dealings. Peter agrees and Harriet sends for him.

Johann Sigurjonsson

[edit | edit source]

Of Icelandic origin, Jóhann Sigurjónsson (1880-1911) reached dramatic heights with "Fjalla-Eyvindur" (Eyvind of the mountains, 1911), based on short story by Jan Arnason in "Icelandic popular tales and fairy-stories (1864)" (Magoun, 1946, p 271)

"Iceland had no feudal age, has no hard and fast divisions of society by race or faith or wealth. Hence, the romantic figure of the outlaw has been one of the very few possible cases where a tragic fate quickened the imagination and sympathy of the simple folk. He is half outcast, half superman, one who dares to defy commonplace human society and, depending upon his own strength, to build up his solitary kingdom in the desert...The dialogue is lithe and tense and telling, relieved here and there by poetic touches that give sure evidence of a powerful imagination working in a world all its own. Above all, the construction is well-nigh faultless in its grandly simple lines" (Hollander, 1912 pp 105-106).

"Eyvind of the mountains"

[edit | edit source]

Time: 1910s. Place: Iceland.

Text at http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/21937 https://archive.org/details/modernicelandicp00jhuoft https://archive.org/details/modernicelandicp00johaiala

Bjorn the bailiff announces to Halla, a widow and formerly his sister-in-law, that her overseer, Kari, has been identified by two men as an escaped convict. Halla does not believe it, but asks Kari whether it is true. At first Kari denies it, but when she asks him to marry her, he says he cannot and admits he is Evynd of the hills, a fugitive of the law. They kiss and become lovers. Their idyll is interrupted by Bjorn with news that he has received an official confirmation by letter of Evynd's true identity. Yet he is willing to ignore the law should Halla decide to become his wife. Halla refuses. Evynd overpowers Bjorn and breaks his leg. The couple flee to the hills. Four years later, the couple are joined by Arnes, a migrant laborer, who attempts to seduce Halla, but she rejects him. Bitter over this experience, Arnes leaves the couple, but rapidly returns to announce he has detected law-officers closing in on them. To facilitate their escape, Halla murders her three-year old daughter. When Bjorn seizes Halla, Eyvind stabs him in the heart and the two escape while Arnes gives himself up to the other officers. For twelve years, Evynd and Halla live under difficult circumstances amid the frozen mountains. In the winter-time, sunlight is minimal. Forced to stay inside their small hut for seven days because of a snow-storm, they become famished and desperate. Evynd decides to brave the storm. "When you go out of that door," Halla warns, "you need not think of me anymore." "You ought to thank me for going out in such weather," an affronted Evynd replies. Halla considers it best to wait out the storm. "We can dig up roots to still the worst hunger, and go to the lake for fish," she proposes. Nonetheless, Evynd opens the door and leaves, hoping to return in two days though unable to see his hand before his eyes. Halla soon follows him. When Evynd quickly returns with firewood, he is stunned to find her gone and with anguish rushes out. A cloud of snow whirls inside the empty hut.

Hans Wiers-Jenssen

[edit | edit source]

Among Norwegian dramatists, Hans Wiers-Jenssen (1866-1925) wrote a historical drama about witchcraft, "Anne Pedersdotter" (1908).

Coiner (1989) considered "Anne Pedersdotter" a "cheap, reactionary tale of passion" (p 128), mostly because he favors a humanistic approach to the "doctrinally most sound" stance of tradition. In contrast, Trewin (1951) provided a truer viewpoint of the play as "doctrinally most sound, as the bigoted Master Klaus would be the first to explain. Wiers-Jenssen’s drama is founded on this belief in Satanic possession and the evil wrought by secret, black, and midnight hags. It opens with a witch-hunt in the home- one of the dubious amenities of domestic life in the sixteenth century- and ends with another in the cathedral itself. Has young Anne Pedersdotter, daughter of a reputed witch, inherited her mother’s dark power? Does she use these gifts to entrap Martin, her husband’s son by a first wife, and to strike Absolon her husband dead? The boy comes to her; the father dies. Anne’s guilt remains undefined, even though, at the last, broken beside Absolon’s coffin, she confesses wildly to witchcraft before her vengeful mother-in-law, and bishop, clergy, and people in the cathedral of Bergen. The tragedy, with its sparely-wrought dialogue, its suggestion of the supernatural, and its climbing terror, can hardly be regarded as an anodyne, but it is exceptionally strong theatre" (p 104).

"Anne Pedersdotter"

[edit | edit source]

Time: 1570s. Place: Bergen, Norway.

Text at https://archive.org/details/cu31924026326854 http://archive.org/details/annepedersdotter00wieriala

The town council sends guards to arrest a presumed witch, Herlofs-Marte, who tries to escape by hiding in the house of Absalon Beyer, rector and castle chaplain. Anne, his wife, reluctantly agrees to hide her. On the same day, Absalon's son from his first wife, Martin, arrives from Denmark and Germany after receiving a master's degree in theology. He initiates friendly relations with his stepmother, almost of the same age as he is, Absalon having been Anne's father's great friend. "I'll lighten your path all I can," Martin promises. The guards trace the accused witch to his house soon after Absalon's arrival. Though Anne denies having seen Herlofs-Marte, the guards search the house and find her in the loft. She is condemned and burnt alive as a witch. Laurentius, a fellow minister, blames Absalon for failing to torture her so that she could name her accomplices. To Anne and Martin, Absalon confesses he has been harboring a guilty conscience for many years, because Herlofs-Marte and Anne's mother had been living as two widows and confessed to him they had "kept themselves by Satan's help". He had not denounced them because of his love for Anne. Alone with her husband, Anne takes him in her arms, but the old man cannot respond to her love. Failing that, she pays more attention to her stepson and they develop a mutual passion for each other. Absalon's mother, Merete, notices how close they have become and does her best to prevent their remaining alone together. "Martin, you ought to be looking out for a good wife," she advises him. "You're at an age when it isn't good for a man to be alone. A good wife and children! The marriage state is well pleasing both to God and man. Marriage drives out Satan, and keeps a man's heart at home." While Anne refuses to think of the future, Martin is tormented by it. "Some day our sin will burst out and cry to heaven," he warns. "If I could burn you in such a flame of passion that you would be blind and forget- forget all, except that we belonged to each other, body and soul, blood and mind!" Alone with his wife, Absalon feels discouraged by his thankless tasks and thinks his lack of passion has done his wife great harm. After his mentioning that he heard her and Martin laugh together, she admits the truth of this. "You robbed me of joy...To wither away, to dry-rot: that was the fate you marked out for me," she confesses. "I have wished you dead and I've wished it most since your son has come home." After also admitting that she and her stepson have lain together as lovers, he has a heart attack and dies. "You've murdered him, Anne Pedersdotter," Merete sputters, "for you....and he...you two..." After his father's death, Martin finds in himself only terror and remorse. He wonders whether Anne is like Herlofs-Marte, laden with the power to kill him. "I shall be burnt if you fail me, Martin," she cries out in terror. During the funeral, Merete accuses Anne of murder and witchcraft. Although Martin starts to defend her, he wonders again to Anne's despair about the matter of witchcraft. When the bishop asks Anne to touch her dead husband as proof of guilt or innocence, she confesses herself guilty of both accusations.

Kaj Munk

[edit | edit source]

Another Norwegian dramatic artist, Kaj Munk (1898-1944), achieved a work of merit with another drama about religion in "Ordet" (The word, 1932).

"The word" is “a religious play written with emotional fervor, penetrating sarcasm and considerable technical skill...The religious opinions of [Borgen and the tailor] are nothing but masked egotism, and the only truly religious spirit is laid, most ironically, in the mouth of an insane man, Borgen's son Johannes, who thinks himself Christ…Johannes restores the dead woman to life. This makes excellent drama...but will hardly make any proselytes among infidels who will still refuse to believe in miracles except in the interesting sphere of Rev Munk's sovereign genius” (Nyholm, 1933 p 164).

"We find a bold exposition of the aggressive yet essentially tolerant Christianity of Grundtvigianism such as Danish literature has never known. It is a comedy, tragedy, and mystery rolled into one; it deals with the trite theme of insincere religion and a paranoiac who believes that he is Christ; and yet all is managed with such consummate dramatic skill and foolproof dialectics that the audience ceases to remember the limits of possibility. At first there is the comedy of Mikkel Borgen, a prosperous farmer who opposes the marriage of his son Anders to the daughter of a poor tailor of a religious confession antagonistic to his own. When Borgen learns that the tailor is against the match for precisely the same reasons, he reveals the shallowness of his religion by reversing his former attitude and attempting to force the marriage. But Borgen and his fellow 'believers' are exposed towards the end of the play by his insane son Johannes, who, very much in the style of Gerhart Hauptmann's Emanuel Quint, believes that he is Christ. In the climactic scene of the play, Johannes, regaining his sanity but retaining his belief, raises the grave...The faith of Johannes triumphs over the combined forces of science, organized religion, and popular prejudice. The hypocritical fanaticism of Mikkel Borgen is described as the Grundtvigianism of an extrovert and that of the poor tailor as the introversion of the lay missionary (a member of a powerful sect in Denmark), but the poet reveals true, national, traditional Grundtvigianism is the strongest of all" (Thompson, 1941 p 270).

“Munk, conservative in form, is original in his reaction against the psychological subtlety of much contemporary European drama and his return to the vigour and passion of the great drama of the past” (Ellis-Fermor, 1946b p 451). "Munk has with rare objectivity caught the essence of the people he describes and has presented verisimilitude in their everyday lives. What imparts certainness of execution to the work can be attributed to Munk's personal wish that a miracle might be possible; the concept of the miracle pervades the play through a recurring, somewhat obscure symbolism" (Arestad, 1954 p 166).

"The word"

[edit | edit source]

Time: 1930s. Place: Jutland, Denmark.

Text at ?

Anders Borgen wishes to marry Anne Skraedder, but his father disapproves because she and her father, Peter, belong to a different religious sect of the Protestant faith. Old Borgen grumbles against the idea all the more vehemently because his youngest son is easily influenced, while his second son, Johannes, is insane to the point of believing himself to represent the second incarnation of Jesus Christ of Nazareth, ever since his girl-friend lost her life by saving his, while the eldest son, Mikkel, is an atheist, which leaves no one to carry on the tradition as head of the farm. But after learning that Peter refuses Anders as a son-in-law for the same religious reason, Borgen is incensed and instantly changes his mind. "You are the best father I have ever had," exclaims a joyful Anders. Borgen encounters a stubborn Peter who seeks to convert him. Failing in that, Peter anticipates trials for him, a prophecy which seems confirmed by a telephone call from Mikkel informing them that his wife, Inger, is in failing health while delivering her baby. Peter hopes that this will open his eyes. Hearing that Peter would rather have her die than the conversion fail, Borgen hits him on his way out. As Borgen returns to his house, Johannes announces he has seen the master with his scythe and hourglass. When Borgen dismisses him, Johannes comments: "There were no works in his native village because of their disbelief." (Matthiew 13:58) Mikkel discloses that the baby has died. In grief and fear, Borgen asks Maren, Mikkel's 7-year-old daughter, to pray for her mother's life. Johannes reveals that Inger will die but he will bring the dead back to life should the family believe in him. After seeing Borgen will not, he cries out: "Woe to you who choke the glory of God in the cadaverous stink of your faith." Then he pleads: "Just one word, it will cost you but one word." But Borgen does not hear. In an apparent fit of inspiration, Johannes sees a great light, to Borgen only the headlights of the doctor's retreating car. Soon Inger dies. From the adjoining room, the two brothers carry in Johannes. "Dead?" Borgen half-hopefully asks. No, he has merely fainted after crying out his dead girl-friend's name. At Inger's funeral, Borgen is surprised to find Peter, who announces he has changed his mind and now consents to the marriage of Anders and Anne so that his daughter may in some sort replace Inger. As they get ready to take away the coffin to the cemetery, Johannes suddenly appears after being missing for five days in the surrounding fields. He now seems to acknowledge Borgen as his father, as the doctor predicted, the dead Inger jarring back the memory of his dead friend. Yet he has not abandoned his belief in bringing Inger back to life. Though Maren is the only one who believes, that is enough, because, to the amazement of the rest of the company, Inger rises from her coffin.