History of Western Theatre: 17th Century to Now/Russian Romantic

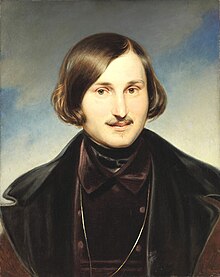

Nikolai Gogol

[edit | edit source]

The most celebrated comedy of 19th century Russia is Ревизор, "Revizor" (The inspector general, 1836) by the Ukrainian dramatist, Nikolai Gogol (1809-1852).

In "The inspector general", "Gogol has constructed a masterpiece, filling it with figures which, in spite of their universal tendency to caricature, are admirably drawn, and attacking all the officialdom of the period. The Governor, with his reproaches to those who rob above their own rank, was particularly a figure which struck the popular imagination. Gogol flies boldly in the face of official optimism, and uncovers the gaping wound of its constitution-the venality and despotism which reigned all over the administrative and judiciary ladder, from the highest to the lowest rung- a thoroughgoing attack, the whole scope of which, as he afterwards proved, he did not thoroughly realise" (Waliszewski, 1900 p 255). "Its stage qualities, which will be appreciated by every good actor, its sound and hearty humour, the natural character of the comical scenes, which result from the very characters of those who appear in this comedy; the sense of measure which pervades it- all these make it one of the best comedies in existence" (Kropotkin, 1905 p 78). "In Gogol’s comedy, we find scorn and anger pushed to the extreme limits; the corruption and incompetence of the official hierarchy are exposed to pitiless mockery; from beginning to end there is not a decent, sympathetic, or estimable character" (Fülöp-Miller and Gregor, 1930 p 38).

“The inclusiveness of Gogol's picture is important to remark. He does show justice (Lyapkin-Tyapkin), education (Khlopov), health care (Gibnerf-Hübner), the post office (Shpekin), welfare institutions (Zemlyanika), the police, the merchants, and so on” (Fanger, 1979 p 136). "The townspeople "have been tricked by Khlestakov, but only because of his greater poise; he can criticize the food given him at the inn more volubly than the Chief of Police can apologize for its inadequacy. The first scene between these two important characters is an excellent example of Gogol’s plan and method. In it Khlestakov thinks that he is being arrested for debt and the chief of police believes that his dishonesty is being investigated by a higher official. Each man is a rogue with certain pardonable weaknesses, each supposes the other to be more respectable than he really is, and each is afraid that his own true character will be detected by his opponent. Gogol’s exposure of personal insincerity and official corruption reaches into every department of governmental activity. Each one of the town’s magistrates is eager to offer money secretly to the supposed inspector on the understanding that he as an individual will not be reported upon unfavorably. The chief of police, who is virtually the mayor of the city, is the principal target for satire. He is a self-made man, who has arrived at his present position by taking bribes and by persecuting mercilessly those who cannot or will not pay him for his patronage...The members of the family of the chief of police, his vain wife and his ignorant daughter, provide the only feminine element...Both mother and daughter are coquettish in their different ways, and each is much interested in clothes and fashions. They are jealous of each other’s place in Khlestakov’s affections. Their rivalry brings about an amusing scene, when the daughter finds Khlestakov on his knees before her mother. This situation is highly farcical, but, like many other ridiculous incidents in the play, it is also a revelation of character. When the Superintendent of Schools lights his cigar at the wrong end, when the chief of police puts a hatbox instead of a hat on his head, when Khlestakov slips and almost falls in his drunkenness, one laughs, but one is made acutely aware of the Superintendent’s nervousness, the chief of police’s excitement, or Khlestakov’s carelessness, as the case may be" (Perry, 1939 pp 321-322). “One of Gogol’s tactics is to subvert conventional dramatic themes. The exaggerated amorous attentions of the city dandy, for example, are based on sentiment so trite that when his propositioning of Marya Antonovna is interrupted by her mother, Khlestakov simply continues his gambit but directs it at another possible conquest” (Hasan, 1986 p 751).

"By limiting its action to that moment in the life of the prefect when he was aroused to activity by the fear of having the numerous misdeeds of his official career brought to light, he has emphasized the pettiness and trivialities of an existence that ignored the higher necessities and obligations of human nature. The expected visit and the arrival of the dreaded revisor form the sole idea of the piece, because in this one event, as in a focus, is concentrated the whole life of the prefect. When we are first introduced to him, he has already assembled the officials of the district to acquaint them with the alarming news he has just received from a well-informed friend that a government commissioner 'is on his way from St Petersburg, travelling incognito and with secret instructions'. During the whole time he has been in office there has been no such inspection on the part of the authorities; but the times are sadly changed; officials are no longer allowed to be bribed, magistrates are expected to administer justice impartially; any little discrepancies in the yearly accounts, which, even when the greatest care is exercised, may occur, are visited with exile to Siberia, and the new-fangled notions of 'Voltairean reformers' have effectually robbed government posts of the profitable advantages they once enjoyed" (Bates, 1903 vol 18 Russian drama pp 126-127)

“Aside from the dramatic effectiveness of this sudden peripeteia, the denouement is strikingly realistic in its merciless humor. Here is no virtue rewarded. There is none to reward. The play leaves neither the impression of peacefulness of comedy nor of the loftiness of tragedy. The particular situation has been brought to a close. The ending is logical, pitilessly inexorable. But the imagination is so stirred by the news of the arrival of the inspector-general, that the people in the play do not seem merely to be on the stage and to cease to exist when the curtain falls. Their life must continue. To make such vivid impressions of reality as opposed to theatricality is the aim of the naturalistic playwrights. Seldom has the aim been attained so completely as in this case. That Gogol was consciously striving for this effect of action continuing after the fall of the curtain is shown by the fact that the first act ends in the same general manner. The governor’s wife and daughter are at the window talking to someone outside, and the wife keeps on shouting and they both stand at the window until the curtain has fallen” (Stuart, 1960 p 595).

“Khlestakov's exceptional vacuity has been the subject of much metaphysical and psychological speculation, but it has a dramatic function. Because he lacks character, the townspeople can project their own fears and fantasies upon him...What makes him so comic is the enormous discrepancy between his own inconsequentiality and the importance the terrified town places upon him...Where comic masquerades before Gogol divided neatly into deceivers and deceived, confidence men and their gulls, in The Government Inspector almost everyone is an impersonator, an actor...Though the play is unremitting in its comic vision, it gives us momentary glimpses of suffering underlying its comedy. Its pathos stems from this sense of loss of selfhood. Deprived of an end to action, the townspeople turn upon themselves...The action between the flash and the crash concludes in an image of social dissolution. The society of the play has pursued an illusion, and in the end its fabric is rent. The message of the gendarme, in Gogol's stage directions, 'strikes like a thunderbolt'. The frenzied whirlwind stops, and all freeze in terror in the dumb scene. The intervention of the central government to set straight a world out of joint provided a standard resolution of comedy before Gogol, but Gogol's inspector is much different from his predecessors. He has no presence in the life of the play" (Ehre, 1980 pp 141-146). “Irresponsible and spontaneous as a child, and much too vain, especially when drunk, to resist a display of his wishful grandeur before the overawed provincials, [Khlestakov] is one of the most consummate innocent liars in literature, since he is always the first to believe everything he says. Like another Poprishchin [in A Madman’s Diary], he needs an imaginary compensation for his actual insignificance, and he finds it in bragging like a megalomaniac. No exaggeration is too much for him as long as he can revel with gusto in all he thinks he is, and make other people think so too...With its motif, its wealth of character and incident,The Revizor stands out as a satirical comedy of the highest rank” (Lavrin, 1951 pp 83-87).

Karlinsky (1969) emphasized the absurdist aspect of the play. "Gogol's use of alogism can be illustrated in its basic form by citing the remark made by the judge in the very first scene of the play. Defending one of his subordinates against the charge of smelling of alcohol, the judge explains that the man can’t help it: his nurse dropped him when he was a baby and since then he has emitted a slight odor of vodka. The explanation, accepted with equanimity by the mayor and other characters, is quintessentially surrealistic, with its deliberate juxtaposition of two prosaic, believable facts (the dropped baby and the smell of vodka) to support a patently absurd explanation...Literary historians have discovered other literatures which use a basic situation similar to the one in The Inspector General and which may have served Gogol as models or precedents. But in all of those plays the young man mistaken for a person of importance and authority is inevitably a clever swindler, a rogue or a picaro, who manipulates the misunderstanding to achieve personal gain and prestige...Cast in the traditional situation of a picaro, Khlestakov nevertheless plays a remarkably passive, almost somnambulistic role in the action of the comedy...The Inspector General can be read as a commentary on the absurdity of human endeavor and human existence, a commentary whose implications go far deeper than any exposure of bribery or corruption in the civil service which may have interested Gogol's contemporaries" (pp 148-149).

"If Gogol is the father of Russian realism, his realism is built upon a romantic basis. Beneath it is the same idealism that underlies Griboyedov’s Woe from Wit, a hope that social conditions may be improved throughout Russia as a result of clearer insight and sounder culture...The weakness of realism is that the numerous physical facts it presents may distract attention from the underlying meaning of a work of art. Its strength is that the emphasis on these same physical facts may stimulate the spectator to a new awareness of the physical limitations of mankind" (Perry, 1939 pp 319-320).

"The inspector general"

[edit | edit source]

Time: 1830s. Place: A provincial town in Russia.

Text at https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/The_Inspector-General https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/3735 http://www.readbookonline.net/title/12075/ https://archive.org/details/revizrcomedy00gogorich https://archive.org/details/inspectorgeneral00gogorich https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.105455 https://archive.org/details/in.gov.ignca.29218

Accustomed to running things their own way, the authorities of a provincial town have a major problem on their hands: the incognito visit of an inspector-general sent by the government. Anton Antonovich, the governor of the town, advises Artemi Philoppovich, the charity commissioner, to clean up the hospitals and to reduce the number of patients. "Otherwise," he worries, "it will at once be ascribed to bad supervision or unskilful doctoring." He also advises Ammos Fyodorovich, the judge, to improve the sloppy management of the court-buildings, as well as the director of schools, Luka Lukich, to take care that the teachers do not grimace at the inspector-general or behave too excitedly. Yet Anton is mostly anxious about his own self. He asks the postmaster a favor. "Look here, Ivan Kuzmich, don't you think you could just slightly open every letter which comes in and goes out of your office, and read it (for the public benefit, you know), to see if it contains any kind of information against me, or only ordinary correspondence?" The postmaster accepts. Ivan Alexandrovich Khlestakov, a copying clerk short of funds at an inn, is mistakenly taken for the inspector-general. In their first meeting, Anton and Ivan look at each other nervously, until the former lends him 400 roubles to settle his bill at the inn and invite him over to his house. As the inspector-general, Ivan is taken to the hospital, where Artemi boasts. "The patient no sooner gets into the sick-ward than he's well again." he says. "It's not so much done by the doctoring as by honesty and regularity." For his part, Anton boasts on the "multifarious matters that are referred to him". Ivan is led to boast as well, particularly about his writing for the papers and the opera, and about the power of his government position, so that all the local authorities are awed and become all the more frightened. As Ivan sleeps off a heavy dinner, the governor has the following warning for the police officers: "Just mind, if any one comes with a petition, or even without one, if he looks like a person who would present a petition against me- then you kick him out head-foremost- straight!" while exiting on tiptoe to prevent disturbing the supposed inspector-general's sleep. When Ivan awakes, Ammos introduces himself nervously, drops as if by chance some bank-notes, and is relieved when asked to lend them to him. He is followed by Ivan Kuzmich, who lends him some more, followed by Luka, propelled from behind as a result of his cowardice and nervously lending him even more, along with two landowners, Bobchinsky and Dobchinsky, the latter requesting a favor concerning his bastard son: "And so, if you please, I wish him to be quite my- well, legitimate son now, sir, and to be called Dobchinsky, like me, sir," he says. "I most respectfully beg of you, when you return to Petersburg, to tell all the different grandees there- the senators and admirals- that here, your serenity- I mean, your excellency- in this very town lives Peter Ivanovich Bobchinsky, merely to say that: Peter Ivanovich Bobchinsky lives here," says the other, to which Ivan responds: "Certainly!" They are followed by Jewish merchants complaining about being "grievously and unjustly oppressed" by the governor, which Ivan promises to look into, not for a bribe but for a loan of some roubles. Two citizen's wives follow, also complaining of the governor's enormities. The governor's daughter, Marya Antonovna, next comes in, with whom he unhesitantly flirts, kissing her shoulder, dropping to his knees, till discovered by her mother, Anna Andreyevna. He assures her of not being in love with her daughter. "No, I'm in love with you," he swears instead. "My life hangs on a thread. If you will not crown my constant love, then I am unfit for earthly existence. With a flame at my heart, I ask for your hand." to which she responds: "But permit me to mention that I am, so to speak . . . well, I am married." When Marya discovers him on his knees again, she is browbeaten by her mother till Ivan asks for the daughter's hand, which astonishes both women, though both accept his proposal. After another 400 rouble loan to round out the previous 400 roubles, Ivan quietly departs the scene to visit a wealthy uncle. Anton summons back the merchants, revealing that the inspector-general is to be his son-in-law, at which point they become quite humble. While Anton and his wife brag about their son-in-law, the postmaster announces he has found out by opening his letter that the inspector-general is no inspector-general. When the real inspector-general is announced, the confounded authorities mutely stand still.

Alexander Griboyedov

[edit | edit source]

Also of note among major comic works of the period is "Горе от ума" (Woe from wit, 1831) written by Alexander Griboyedov (1790-1829), who describes the social dangers a witty man undergoes in the society of men.

Little (1984) enumerated the opinions of several 19th century Russian authors on "Woe from wit" and its protagonist. Pushkin described Chatsky as a noble, ardent and kind person who had spent some time with a clever man, Griboyedov himself, and had absorbed from the latter ideas, witticisms, and sarcastic remarks. Everything he says is clever but on whom, Pushkin asks, does he waste his words: Famusov? Skalozub? Molchalin? old women? A first mark of a clever man, Pushkin observes, is to know with whom he is dealing...Gogol...complained that Chatsky expresses indignation at what is despicable and nasty in society but does not himself set an example to that society...Pushkin shared Vyazemsky's view that Skalozub and Famusov were superb characterisations, but differed from Vyazemsky on the subject of Sophie, considering her too vague...Both points of view may be reconciled in the light of Mirsky's statement, similar to Vyazemsky's, that Sophie is the only character in the play who is a person rather than a type. All the other characters, he gushes, are universal types 'stamped in the really common clay of humanity', but Sophie is 'a rare phenomenon in classical comedy: a heroine that is neither idealized nor caricatured'" (pp 20-21). “An intelligent and attractive young woman, one of the only people Chatsky admires, Sofia is enigmatic. She reacts very strongly against Chatsky’s acid criticisms of Moscow society, yet she is too intelligent to be unaware of her society’s flaws. Her preference for Molchalin seems to depend more on what he is not than on what he is. Molchalin never exhibits ambition, cunning, or sarcasm. He is always agreeable and silent, a cog in the workings of the state bureaucracy while Chatsky refuses to take part of that system” (Tucker, 1986a pp 815-816).

Griboyedov "knew how to blend social satire with a strong realistic vein and a matchless characterization. His condensed language is racy, dynamic, and almost over-saturated with between the lines. The only drawback of the play is its chief hero, Chatsky, whose witty invectives against society" are at limes long and even tiresome" (Lavrin, 1928 p 16). "Griboyedov’s Woe from Wit is a variation on the theme of The Misanthrope (1666)...The intrigue in Woe from Wit indirectly shows up the absurdity of all the principal characters, particularly the clever ones. Chatsky, Sophie, and the clerk are all duped by their own intelligence, or pretenses to intelligence...The infatuation of the heroine for the worthless clerk is the central incident of Woe from Wit. It is intended to make clear the decadence of the aristocracy and the unprincipled opportunism of the rising lower classes. Griboyedov is so scrupulously fair to his two principal characters that one does not know which of them is the more at fault. Sophie is selfish and cold-hearted, but also ingenious and determined; Chatsky is noble and full of fine sentiments, but vacillating and ineffective. The duel between them is evenly matched, and the battle is undecided at the end. Chatsky angrily shakes the dust of Moscow from his feet, and Sophie is dragged away by her father to the country. It is interesting to notice that Sophie’s father, a corrupt office-holder, refers with approval to certain conditions at the court of Catherine the Great. The same period which was considered the vicious present by the unsympathetic characters in 'The minor' (1782) is regarded as the glorious past by the satirized persons in Woe from Wit. From the comic point of view, what seems to many people unbearable at a given moment will, in the course of time, shine brightly by the reflected light of other evils, which as yet they know not of. This emphasis on change, social and political, is one of the noticeable factors in the history of Russian comedy" (Perry, 1939 pp 317-318).

“Griboedov was basing on Byron not only the features of his hero, Chatsky’s world outlook, but also the main conflict in the plot, Sofia’s invention of Chatsky’s craziness...The image of Chatsky is the first and- alas!- right up to the present- the only effective and consistent portrait of individualism in Russian literature on a European scale. It is an image not so much of a hero as of a Romantic anti-hero in Russian life, not the rule, but an exception. Proud, smart, caustic, open, unprotected, detesting lies and hypocrisy...Chatsky...does not wish to be reconciled, does not wish to pretend, does not wish to look like everyone else...Chatsky appears happy, energetic, witty, self-confident, deeply sensitive, open to the whole world, similar to Hamlet before the meeting with the ghost of his father. He craves activity; he is full of optimistic hopes, he jokes, entertains. His enthusiasm, lifting the soul a little, his rare gift of eloquence a result of constant work on his ideas and spiritual development...Experiencing ‘a million agonies’,...he becomes jaundiced, nagging, immeasurably irritable and, boiling with rage, continues to expose the lie, flinging himself on everyone indiscriminately, passing a merciless sentence on Moscow before abandoning her forever” (Gershkovich, 1994 pp 283-284).

"Woe from wit"

[edit | edit source]

Time: 1820s. Place: Moscow.

Text at http://samlib.ru/a/alec_v/woehtm.shtml https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.105455

Early one morning, Famusov surprises his daughter, Sophie, talking with his secretary, Moltchalin, and suspects the worst, though the latter pretends to have just arrived. "This is what families gain when one reads from morning till night!" Famusov complains. "Always these stores, that cursed France, her muses, authors, elegances: executioners of pocket and heart! O, may the Creator spare us from hats, silken garments, hairstyles, hors-d'oeuvres, and literature." Moltchalin distracts him by mentioning some papers that must be signed, to which his superior replies: "I have my method, it is incontestable; a paper is shown me: read or unread, I sign, and that's that." After both leave together, Sophie is surprised by the arrival of Chatski, back after three years of traveling, but already criticizing Moscow-life. "Where can one live better?" Sophie asks. "Where we are not," replies Chatski. Alone with her father, he makes known his interest in Sophie, but is immediately rebuffed by complaints on the frivolities of modern youth. Piqued, Chatski responds by criticizing the style of the previous generation. "Those who bent themselves lowest had the greater glory," he declares. All his comments highly displease the conservative father. Their talk is interrupted by the arrival of a military man, Skalozob, whose conversation is more acceptable to the father. After bragging about Moscow's refinements, Famusov tells the colonel about how Chatski fritters away his talents, to which the latter retorts: "Everything makes me despair of you, even your compliments." Famusov soon leaves. Sophie suddenly enters and rushes to the window after having watched Moltchalin fall from his horse, then faints. While Chatski helps to revive her, Skalozob brings in Moltchalin with a bandaged arm. Sophie's servant comments that Skalozob will laugh with others at her fainting spell. Talking apart, Sophie reveals her feelings to Moltchalin. "I was ready to jump out to you from the window," she confesses. "What do I care for them, or of the entire world? Let them protest and laugh: I wish to know nothing." Later, Chatski confronts Sophie about her sentiments towards him, who replies that she is repulsed by his constant criticisms, in contrast to the "modest, calm, and tender" Moltchalin. Indeed, while speaking with Chatski, Moltchalin admits to being unapt to criticize. "I can barely express my own judgment of things," he affirms. Chatski cannot believe she can love such a fellow. At a ball, Chatski meets Plato, an old army friend, and is dismayed to discover how much he has changed under the influence of a domineering wife. A rumor circulates among the guests that Chatski is insane, approved by Famusov, who is only surprised to find the man still at large. Chatski enters launching into a tirade against a man from Bordeaux only to discover no one is listening. That night, he greets Repetilov, enthusiastic over his revolutionary or bohemian friends at the English Club. After listening without interest, Chatski disappears and becomes a witness of an unpleasant night-scene, in which Sophie discovers Moltchalin in the arms of her servant. Enraged, she threatens Moltchalin to divulge everything to her father unless leaves the traitor the house forever. He leaves submissively. Chatski leaps forward to seize his chance, but is interrupted by the father, angry to find Sophie in company of a man late at night and vowing to send her off in some remote area in the care of an aunt. A disgusted Chatski decides to leave Moscow.

Alexander Pushkin

[edit | edit source]

"Бори́с Фёдорович Годуно́в" (Boris Godunov, 1830) by Alexander Pushkin (1799-1837) is one of the most famous Russian tragedies of the Romantic period.

"Boris Godunov", "taken from the times of the pretender Demetrius, is enlivened here and there by most beautiful scenes, some of them very amusing, and some of them containing a delicate analysis of the sentiments of love and ambition; but it remains rather a dramatic chronicle than a drama" (Kropotkin, 1905 p 47). “Pushkin was deliberate in this effort to impart a new direction to Russian drama. He felt that the attempt was to be of importance to his country’s literature, and he set about planning the work with the greatest of care. The material of his play he obtained largely from Karamzin’s History. The action covers the period from 1598 to 1605, and concerns the reign of Boris Godunov and the usurpation of the False Dmitri...The central tragic situation is infected by Karamzin’s sentimental treatment of the subject, and on the whole the verse is static. At times the scenes and characters do not come to life, and there is little of the sustained dramatic power of Shakespeare. But as a pioneer work it deserves high praise. There are some brilliant scenes and splendid passages of rhetorical poetry. Compared to any drama that had preceded it in Russia, Boris Godunov is an extremely fine performance, and its place in Pushkin’s development is of prime significance. He completely effaces himself from the play” (Simmons, 1964 pp 234-235). "The tragedy of the usurper Boris, who removed Ivan the Terrible’s heir, Dmitry or Demetrius, in order to make himself tsar of Russia, is permeated with anguish born of a sense of guilt. The portrait of the ambitious monk who pretends to be Demetrius is vividly executed, and powerful mob scenes bring the masses into the historical picture. 'Boris Godunov', for all its structural flaws, is a vivid evocation of seventeenth-century Russia and a well-realized study of criminal ambition" (Gassner, 1937, p 342).

"Pushkin drew most of the material for his drama from the tenth and eleventh volumes of Karamzin's History of the Russian State...The tsar's opening speech is an excellent example of the poet's ironies and ambiguities. The tone of this address, at the same time majestic and nostalgic, seems to imply a moral compensation, ridding the speaker of a personal feeling of guilt...The tragic tone of Boris' second speech- now a soliloquy to suggest his growing alienation from the people- already indicates his gradual transformation from a powerful tsar into a guilt-ridden man, who feels himself punished not only as a king but also as a father...He is unable to stop the advance of the false Dimitri, and the people, living under the stress of severe critical turmoil, and sensing a possibility for a change in their lives, begin to challenge his authority. Feeling more and more insecure on his throne, Boris becomes unresponsive to the people, suppresses their civil rights, and puts the protesters in prison. As the storm approaches he becomes more and more an internal emigré of spirit, self-enclosed, lonely, and turns to magicians and fortune-tellers for support...At the end he reveals the mark of age and the ravages of time accelerated by a sense of guilt. His sudden physical sickness is a symbol of the spiritual malady that has overcome him. In his last speech he admits that he should have died in darkness like all the other subjects of the tsar and not as the possessor of the highest power. His death comes as a necessary act of purgation and retribution. Yet he still has enough strength left to try to save his son who is dearer to him than the salvation of his own soul, and gives young Feodor wise, statesmanlike advice born of many years of political experience. However, his thoughts keep returning to the 'wilful and hidden wrongs' he had done and he begs his son not to ask him how he 'attained the highest power'. ..Dimitri's real logic is his passion, energy, ambition and ingenuity. He acts on instinct and impulse and lets himself float on waves of the current, 'feels' rather than knows people and things, senses the turn of tides and events, and has a way of listening to, and catching the essence in this world of uncertainties. Except for a momentary lapse when confronted with Marina Mniszek, he shows an ability to find the right word for everybody in every situation, and reveals his competence to validate words with deeds. Pushkin stresses his capacity for leadership and responsiveness to new situations as they arise, perceiving the directions they are taking...In this world of treachery and betrayal, Shuysky, this true 'politician', knows that he must constantly wear a mask. Thus, openly he is loyal to Boris, although the Tsar suspects him, but secretly conspires to do everything to help Dimitri, whom he knows to be a false pretender, to unseat Boris...Basmanov's decision reflects the confused ethics and shifting allegiances in which no absolute loyalty is possible, and the decision is made, in analysis, not on moral, but on simple pragmatic grounds. It is not seen as stamp of approval but rather as the life-affirming power of recognizing the necessity for survival...Marina is the ‘femme fatale’ of the drama who almost ruins Dimitri's plans. The pretender remains steadfast in his role throughout the play, he almost loses his assumed identity during a stormy scene with Marina. Overcome by love for the beautiful Polish girl, Dimitri's manly pride is hurt when he understands that Marina does not love him, the human being, but only his 'mask', Tsarevich Dimitri, and attempts to disclose his true self in order to preserve his human dignity. However, the ambitious Marina haughtily rebuffs him, calling him a 'poor imposture' 'worthy of the shameful noose', and even threatens to expose 'his bold and insolent fraud to everyone’...'Boris Godunov' opens with the recollection of Tsarevich Dimitri's murder and ends with the murder of Boris's innocent wife and son" (Brody, 1977 pp 861-874). “One of Pushkin’s great strokes of characterization is to have Boris die with a clear conscience, having accepted the punishment due to him. Nevertheless, his guilt is visited upon his own son, who is killed at the end of the play” (Tucker, 1986 p 1497).

In history, “there is no evidence that Boris did kill the tsarevitch. He profited from what seems to have been the accidental death of an epileptic child...Pushkin makes some play with the tsar’s guilt, but the whole tendency of the play is to show that it has the most indirect connection with the march of events. The boyars spread and exploit the rumour that Boris had attempted but failed to kill the tsarevitch, who is now coming to claim the throne; for their own ends they make use of the pretender and are as indifferent as his Polish supporters to the actual authenticity of the claim. They are carried forward by the rising tide of popular feeling which they have helped to manipulate, and it is ironic that the Pushkin who is a boyar in the play, and the poet’s ancestor, can claim with perfect truth to Boris’ general Basmanov that it is useless for him to struggle any longer against popular sentiment...Boris’ death, though opportune for his opponents, is merely an incident, not a climax. History gives the impression of not being interested in drama...[Dimitri’s] passion for Marina is an aspect of the Renaissance gallantry that he has acquired from his new environment. He wishes to appear to Marina not in his role as tsarevitch but in the new guise of confidence and chivalric spirit which he himself created for himself. She, on the other hand, has no interest in what he is himself but only as the tsarevitch, the instrument for her own ambition” (Bayley, 1971 pp 168-174).

"Boris is not merely a hypocrite and a tyrant, but is also endowed with those generous impulses common to us all, and in spite of his crimes, more than once wins our sympathy as he tries to gain the love of the people by his deeds of mercy. In the same way Gregory, the false Dmitry, is no vulgar impostor; but his youthful thirst for action and his readiness, at the moment when success seemed most assured, to sacrifice all for the love of Marina, enlist something more than interest in his fate and raise him above the ranks of an ordinary stage hero...Shouisky is the perfect type of a time-serving, place-seeking courtier, who yields to authority while it is strong, never allowing himself to come into collision with it, but the instant it betrays weakness, turns against it and becomes the foe of that which he had before affected to worship" (Bates, 1903 vol 18 Russian drama p 92).

"Boris Godunov"

[edit | edit source]

Time: 1590s-1600s. Place: Russia, Lithuania, and Poland.

Text at http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/5089 https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Boris_Godunov

Prince Shuisky explains to Prince Vorotynsky that he has reason to believe that Boris Godunov, a favorite of the previous czar, murdered his last son and heir, Dimitry, to obtain the crown, but, afraid to be disbelieved, as "the czar saw everything through the eyes of Godunov", kept silent. When the crown is offered him, Godunov pretends to refuse but at last accepts it. "My soul is bare before you all," he declares, "you, father patriarch, and you, boyars, you saw I accept the greatest power in fear and trepidation. How heavy is the obligation on me!" A few years later, a monk named Grigory escapes from a monastery after expressing seditious comments, including that he will one day become the czar. Officers-of-the law pursue him inside an inn near the Lithuanian border, but they do not recognize his face when they see him. When asked to read the characteristics of his person in the summons of his arrest, he describes one of his companions, but is found out. Nevertheless, he succeeds in escaping from them. A nobleman, Pushkin, tells Shuisky it is rumored that Dimitry is still alive, which the latter knows to be impossible, having seen the corpse. Nevertheless, the news is believed by many to be true. Soon Shuisky announces to the czar startling news. "An impostor has appeared in Cracow," he says, "and the king and nobles are behind him." Godunov begs Shuisky to assure him Dimitry was not substituted for another, which he does. The impostor is Grigory, who assembles an army composed of Poles, Lithuanians, and Russians, in mass revolt against the czar of Russia. In the midst of this turbulence, Grigory courts Marina to be his wife. He has doubts whether she loves him for his own self or for his power, and so divulges his identity to her. Though at first dismayed by this gigantic fraud, she is reconciled to him after witnessing the extent of his boldness and promises absolute secrecy. Although his forces outnumber the enemy's, Godunov worries over a patriarch's story of how a blind man recovered his sight over Dimitry's grave-site. Other sufferers have been saved, so that the patriarch recommends the transfer of the relics to the Kremlin palace. Instead, Godunov exhorts the people in the public square, but, struck by a sudden sickness, he can go no further and dies, his son becoming the new czar. Nevertheless, Grigory pursues his purpose with Pushkin on his side, who seeks to tempt one of the czar's worthiest boyars, Basmanov, into accepting a high position should he come over on their side. Though Basmanov refuses, the czar's forces are overcome, he and his mother committing suicide, to the people's silent horror.

Mikhail Lermontov

[edit | edit source]

Another poignant tragedy of the period, "ДВА Без перевода" (Two brothers, 1836), was written by Mikhail Lermontov (1814-1841).

"Two brothers" "tells of the victimization of a woman by the three men in her life. They are the idealistic Yury, whom she once loved, Yury’s cynical and sadistic brother, Aleksandr, who debauched her, and the dim-witted prince whom Aleksandr had forced her to marry. The heroine is Vera Ligovskaya, who was later to appear in somewhat altered form in Lermontov’s unfinished novel, Princess Ligovskaya. She also appears as Vera in Hero of Our Time. Her fate in The Two Brothers is a prerequisite for understanding her character in those two later works of prose fiction. The evil Aleksandr and the sensitive Yury may well be derived from the similarly contrasted pair of brothers in Schiller’s The Robbers" (Karlinsky, 2013 p 82).

“The brothers both respect and detest high society, desiring a social life as well as solitude. They are violent and intense men who are inclined to jump to conclusions. At the first sign of betrayal, their rage is uncontrollable and they seek immediate revenge” (Kashuba, 1986b p 1075). "Yury is the gay and dashing young officer who has easily won the affections of Vyera as a young girl. He has apparently made no move during his years of military service to maintain the relationship and he feels bitterly that she has married a rich man for whom he has himself no respect. He is frank, open and attractive both in his virtues and his vices. He promises his father that he will respect Vyera's marriage as long as she does not take the first step to reopen the affair, but he will not promise more than he can be sure of accomplishing. In fact he takes no action until Vyera's husband, deceived by his recital of his former love for her, tells him that the wife still loves him. On the other hand, Alexander is far less attractive. He has lived at home with his aged father and has met with rebuffs at every attempt to win those rewards which came so easily to his brother. When for a moment he had aroused the attention of Vyera, he had reached the summit of his happiness and his whole life was absorbed, colored and warped by this apparent success, even though he was fully aware that he was only taking his brother's place" (Manning, 1948 pp 151-152).

"Two brothers"

[edit | edit source]

Time: 1830s. Place: Moscow, Russia.

Text at ?

After a four-year absence, Yuri returns to find Vera, his old love, married to Prince Ligovski. "She cannot be happy," he mournfully comments to his brother, Alexander, while his father, Dimitri, is equally convinced that she cannot love her husband, which Alexander denies. As the prince enters with his wife, he expresses satisfaction about the lodgings Dimitri prepared for him. Alexander laughs over news that one of the prince's neighbors wept on hearing her daughter refuse an offer of marriage from a millionaire. Yuri finds the anecdote not in the least funny. "In her place, I would have fallen sick," Yuri wrily comments. "With a million, there is no need of a face or a mind, neither soul nor a name, a million suffices for all that." When the rest leave, Vera requests Alexander to tell his brother how hurt she was by his indirect comments on her husband's wealth. Alexander accepts. "To prove my love for you," he adds. In the presence of Ligovski and Vera, Yuri confesses he loves a married woman. Unaware of who he is talking about, the prince advises him to press his suit. Seeing Yuri bolder than before, Vera tells Alexander she now hates him. Jealous of both the husband and his brother, Alexander tells his father that Yuri loves Vera and asks him to reveal this to the prince. Unsure of the wisdom of this move, he nevertheless does so. Stunned at these news and humiliated by Yuri's revelations and his own comments, the prince decides to leave Moscow. Dimitri tells Yuri what he has done. Yuri is incensed, assuring his father he will never forgive him. Desperate to see Vera one more time, Yuri first promises a great reward then threatens with death a servant should he fail in delivering a letter to her. Alexander overhears this conversation and bribes the messenger to show him the letter, in which his brother implores her to meet him at midnight. In the dark, mistaking Alexander for his brother, Vera confesses she still loves him, though they must separate, at which point Alexander reveals himself. He takes her in his arms, then, seeing her grow limp, hides behind a post as Yuri enters and confesses his love for her. She rejects him weakly. As he advances closer, Alexander reveals himself again, enabling her to run away to her husband, who assures her that she will no longer enjoy the freedom of a wife one may have confidence in. "You will be confined in a village in the steppe and there you will sigh while looking at the lake, the garden, and the fields," he declares angrily. The next day, with their father on his death-bed, Alexander confesses to Yuri that, in his absence, Vera became his lover. Yuri receives these news with anguish as his father dies.