History of Western Theatre: 17th Century to Now/English Pre-WWII or Edwardian

The Edwardian drama refers to the reign of King Edward VII (1901-1910). The realistic mode prevalent at the end of the past century prevailed at the start of the 20th.

"The tendency of modern dramatic art is now to make the characters and the emotional and moral significance of the situations the most important elements, and to reduce the plot to a minimum. The characters in consequence are not merely presented during the early scenes, but go on developing till the end of the play, so that the spectator may have to alter his first impressions. In consequence, the faculty upon which the modern play tends to rely more and more in the spectator is no longer the power of following the indications of a complex story, but of seizing and remembering shades of character and emotion; and the spectator's pleasure depends now not so much on being unable to guess what is going to happen next as in being able to recognize that what does happen next is true and interesting" (MacCarthy, 1907 p 18-19). “The drama of today, through the influences of modern science, of contemporary democracy, of shifting moral values, of the critical rather than the worshipful attitude toward life, of an irresistible thrust toward increased naturalism and greater veracity, has become bourgeois, dealing with the world of every day; comic, verging upon the tearful, or serious, trenching upon the tragic; unheroic, suburban, and almost prosaic, yet intensely interesting by reason of its sincerity and its humanity; essentially critical in tone, proving all things, holding fast that which is good” (Henderson, 1914 p 309).

“The English, as their drama represents them, are a nation endlessly communicative about love without ever enjoying it. Full-blooded physical relationships engaged in mutual delight are theatrically tabu. Thwarted love is preferred...At the end of a play on some quite different subject- religion, perhaps, or politics- it is customary for the two to say, as he does in [St John Ervine's Robert’s Wife (1938)]: ‘I was deeply in love with a fine woman’ and for the wife to reply: ‘My dear, dear husband!’ but there should be no hint elsewhere in the text that they have as much as brushed lips. In comedies, marriage is presented as the high road to divorce. Husband and wife begin the play at daggers drawn at their country house, and the whole point of the ensuing exercise is to lure them back into each other’s arms. The reconciliation takes place in the last act. Left alone on stage, the two lovers exchange coy salutations…Among younger people, the technique of courtship is even more rigorously codified...He is always bashful and ashamed in the presence of women to whom he is not closely related. The plays of the twenties were full of scenes in which the hero, contorted with grief, confessed to his mother that he had transferred his affections to another woman. A firmly established tenet of the English drama is that love which is only physical will not last, and is probably ghastly anyway...The idea that a man and a woman should...sexually exult in their discovery is deeply offensive to English taste. Someone should suffer for it, and our playwrights see that it sometimes does, harshly and irrevocably. Proposals are regarded with more tolerance, though the approach to them is often extremely oblique...English romantic drama is built around interrupted and frustrated embraces. Uninterrupted embraces only take place years before the curtain rises…Actresses, by an unjust dispensation, have far fewer chances. Prejudice forbids them any form of self-indulgence. Until she reaches the age of thirty, the English actress is allowed only to play ingenues, girls too young for love and scared of it” (Tynan, 1961 pp 61-64).

"Until the modern period, great drama has possessed not only those deeper and subtler qualities which reveal themselves to the careful analyst and which constitute its greatness, it has also possessed more generally available qualities. It has appealed on different levels. It has appealed to the connoisseur and the amateur, the critic and the public. It has functioned as mere entertainment for some and as the highest art for others. A great deal of modern art, however, including drama, does not possess this double appeal. It appeals only to those who can discern high art, just as modern entertainment frequently appeals only to those who are satisfied with mere entertainment. Scandalized, our spiritual doctors call on the entertainers to be artistic or on the artists to be entertaining. The one class is censured as low-brow, the other as high-brow. Whatever the proposed solution, wherever the blame is to be placed, the facts themselves are inexorable. A peculiar, problematic, and perhaps revolutionary situation exists. Art and commodity have become direct antagonists" (Bentley, 1955 p xv).

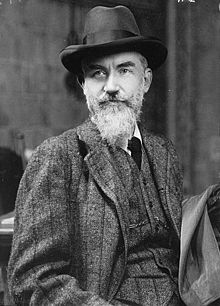

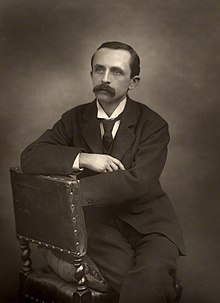

George Bernard Shaw

[edit | edit source]

The Irish-born playwright, George Bernard Shaw (1854-1950), continued work from the previous century by becoming one of the major dramatists prior to World War II (1939-1945), whose best-loved plays include "Mrs Warren's profession" (1902, first written in 1893), "Man and superman" (1903), "Major Barbara" (1905), "Pygmalion" (1912), and "Heartbreak House" (1919).

"Mrs Warren's profession" resembles two stories by Guy de Maupassant (1850-1893): “Yvette” from the book of short stories of the same name (1884) and “Yveline Samoris” from the posthumous book of short stories “Father Milon” (1899) in which a daughter rejects the life-style of her courtesan mother, in the first story outliving an attempted suicide with chloroform in despair at being forced to live a similar life-style and in the other dying from the same cause. Early critics were offended by its theme. Chesterton (1914) explained that the play "is concerned with a coarse mother and a cold daughter; the mother drives the ordinary and dirty trade of harlotry; the daughter does not know until the end the atrocious origin of all her own comfort and refinement. The daughter, when the discovery is made, freezes up into an iceberg of contempt; which is indeed a very womanly thing to do. The mother explodes into pulverising cynicism and practicality; which is also very womanly. The dialogue is drastic and sweeping; the daughter says the trade is loathsome, the mother answers that she loathes it herself; that every healthy person does loathe the trade by which she lives. And beyond question the general effect of the play is that the trade is loathsome; supposing anyone to be so insensible as to require to be told of the fact. Undoubtedly the upshot is that a brothel is a miserable business, and a brothel-keeper a miserable woman. The whole dramatic art of Shaw is in the literal sense of the word, tragi-comic; I mean that the comic part comes after the tragedy" (pp 137-138). For his part, Grein (1902) refused to allow the subject of prostitution in a rational discussion. “The case of Mrs Warren has been invented with such ingenuity and surrounded by such impossibilities that it produces revolt instead of reasoning. For Mr Shaw has made the great mistake of tainting all the male characters with a streak of a demoralized tar brush; he has created a coldblooded, almost sexless daughter as the sympathetic element and he has built the unspeakable Mrs Warren of such motley material that in our own mind pity and disgust for the woman are constantly at loggerheads. If the theme was worth treating at all the human conflict was the tragedy of the daughter through the infamy of the mother. Instead of that we get long arguments- spiced with platform oratory and invective- between a mother really utterly degraded, but here and there whitewashed with sentimental effusions, and a daughter so un-English in her knowledge of the world, so cold of heart, and 'beyond human power' in reasoning that we end by hating both; the one who deserves it, as well as the other who is a victim of circumstances. Thus there are false notes all the time, and apart from a passing interest in a few scenes, saved by the author's cleverness, the play causes only pain and bewilderment, while it should have shaken our soul to its innermost chords” (pp 294-295). "“Here, not only a stock subject of philanthropic reformers, but the whole of Nordic middle-class mentality with regard to the phenomenon of prostitution is taken by the horns. Shaw argues that it is either a social necessity, and then there is no reason for keeping poor Mrs Warren and her former lodgers in a state of inferiority (this state of inferiority, on the contrary, in its turn causes the evil to grow worse); or else it is an evil that can be corrected, in which case society should correct it by eliminating its causes, and not by reviling those who are the first and principal victims of such causes. This is a very good argument, but, as usual, one-sided, because it leaves out altogether the psychological and moral aspect of the problem, which is perhaps better and more generally understood in the Latin countries than among the puritan Anglo-Saxons. There remains the drama of Mrs Warren, who after all is an excellent woman, in relation to her daughter, who is also a striking figure, a girl who has been made hard and inhuman through a badly conceived system of education” (Pellizzi, 1935 pp 83-84). Henderson (1914) complained that “driven by his ineradicable sense of the ridiculous, Shaw has greatly weakened the play's effect by shattering unity of impression through the gruesome, cynical levity of Frank” (p 81). In contrast, Duffin (1939) appreciated Frank. "Regarded from a distance, the play appears as a setting for the three scenes: between Frank and Vivie: the babes in the wood, in the middle of Act III; the disclosure of the relationship, at the end of Act III; and Vivie’s renunciation in Act IV- with the scenes between Vivie and Mrs Warren as lower lights. As a reason for Vivie’s repudiation of her mother’s money, any other disgraceful way of getting rich would have served; but the fact that Mrs Warren is a leader in this special business makes possible also the most interesting psycho- logical problem of the play- the brother-and-sister-lover relationship. The situation is handled with such skill and sympathy by Shaw- mainly through the exquisite creation of Frank Gardner, who is among the most wonderful of Shaw’s young men- that it not only escapes all taint of unpleasantness, but actually becomes one of those gracious loves that are uncharacteristic of Shaw. Frank is not affected by the conventional idea of a necessary repulsion- he feels nothing of the sort, and does not trouble about what he ought to feel. His attempt to throw doubt on the facts of their relationship, as stated by Crofts, is undertaken merely for Vivie’s sake. She, too, declares she is unaffected by the revelation, though her denial is inconsistent with the despair and disgust she evinces when it is made, in contrast to Frank’s magnificent acceptance, which is, however, I suppose, only a romantic gesture in face of Vivie’s realistic grasp of the situation. The idyll flickers out abruptly, but its three brief scenes leave much that is beautiful upon the memory” (p 67). “Vivie is...offered 4 choices: Frank (romantic love), Praed (escape from reality into art through aestheticism), Mrs Warren (sentimental attachment to mother no matter what the mother does), and Sir George Crofts (co-opting within an evil system for the sake of money)...Vivie’s decision to join the law-firm of Honoria Fraser is neither cynical nor misanthropic. She simply makes the wisest and most mature choice available to her, a choice clearly superior to the other four” (Abbott, 1989 p 47). “Vivie, who began by reproaching her mother for her way of life, becomes gradually impressed by her energy and ability, and touched by the sacrifices she has made for her. But when she learns that her mother is still continuing to follow the same profession, her mood changes and in the final scene they face each other as enemies...Vivie...tells her that at heart she is a conventional woman, and that is why she is leaving her...What spoils this powerful drama is above all its tone, which is too light for the subject with which it is dealing” (Lamm, 1952 pp 260-261). Gassner (1954a) admitted that "Mrs Warren's Profession releases a powerful barrage, its larger purpose being defined by Shaw in his 1898 Preface with customary precision: "I believe that any society which desires to found itself on a high standard of integrity of character in its units should organize itself in such a fashion as to make it possible for all men and all women to maintain themselves in reasonable comfort by their industry without selling their affections and their convictions'" but yet the critic moaned about the "dubious artistry of the piece; once Mrs Warren has made her forceful confession to her daughter, the action is whipped up into hopelessly thin lather concerning Vivie Warren's decisions respecting her own life, and despite affirmations of feminine independence (the New Woman!) she becomes a tiresome and chilly subject" (p 602). Likewise, Agate (1926) wrote that "there is one great flaw in the piece, which time has not altered, and that is the nature of Mrs Warren’s crime. To sin in one’s own person is one thing, to traffic in sin is another The woman’s case is too thin here, and the statement that her creatures were happier than the average barmaid or the average wife of a Deptford labourer is simply not true. Mrs Warren herself is drawn in the round, the rest of the characters are mere intellectual abstractions. Vivie, in so far as she is alive at all, is a prig, Crofts is a sawdust monster, Frank is very little removed from a scatter-brain, and the clergyman and the artist are just not anything at all" (p 233). In contrast to those critics, Mair and Ward (1939) felt that the play "made a brave and plain-spoken attempt to drag the public face to face with the nauseous realities of prostitution" (p 205). Archer (1899) felt that "the character of Mrs Warren is superb, the indictment of the economic conditions which beget Mrs Warren's and their bondwomen is thrilling and crushing, and the technique is throughout admirable, especially in the natural yet intensely dramatic manipulation of the great scenes. There are speeches whose irony takes you by the throat, both in the scene in which Mrs Warren expounds to her Girton-bred daughter the nature of her profession, and that in which Sir George Crofts, Mrs Warren's partner, in the private hotels which she manages, amplifies the mother's revelations. The former scene, to be sure, would be far more poignant if Vivie were a human girl instead of Mr Shaw's patent, imperturbable Girtonian paragon; but in that case it would be too painful for endurance. The scene with Crofts, on the other hand, gets its point from Vivie's intellectual competence...Much as I dislike and shrink from certain passages between Frank and Vivie, I have no hesitation in saying that Mrs Warren's Profession is not only intellectually but dramatically one of the very ablest plays of our time" (pp 9-10). “The characters in Mrs Warren's Profession are wonderfully well drawn, especially Mrs Warren, who is, as the author describes her, a disreputable old blackguard of a woman, but all the same she is alive and intensely interesting. But disreputable folk sometimes make better parents than the most respectable, when they make up their minds to it. They know their faults so well that they can keep them in the background. Both Frank and Vivian...are instances of their parents’ success in this respect. Mrs Warren's men friends are of the kind one might expect; at the same time they are the pick of her basket. Some may regard it as questionable taste on the author's part to have made the father of Frank a clergyman, but nature is no respecter of persons or parsons, and the author of such a play as Mrs Warren's Profession is scarcely the man to pander to superstition” (Armstrong, 1913 p 254). "There is a conflict between Mrs Warren, the well-balanced woman of business, reasonable, tenacious, active, hard-working, and ambitious, but a sentimentalist who has lived one kind of life while dreaming of another and Vivie, the true daughter of the mother, likewise well-balanced, reasonable, tenacious, active, hard-working, and ambitious, but stronger willed, positive, and realist, wishing to live a real life. There is a conflict between Vivie and Crofts, an elderly sensualist, still robust, maintaining the veneer of respectability, attracted by Vivie's youth and vigorous beauty. There is the conflict between Vivie and Frank, positive-minded but an idler, who wants a practical, sensible, and well-to-do woman for his wife, to enable him to continue his enjoyments as a gamester and a sportsman. There is the conflict between Frank and his father, the Rev Samuel, who is authoritative, irritable, and weak-willed—in fine, somewhat ridiculous, and really under his son's influence...All these conflicts taken together manifest to us also a general conflict, that between capitalist society and a moral ideal altogether different from traditional morality, one which finds no overt expression, but which is felt to exist all through the play, to which it gives a high moralizing value"(Hamon, 1916 pp 169-170). The play's "strength proceeds from the depth displayed in the consideration of the motives which prompt to action, the intellectual and emotional crises eventuating from the fierce clash of personalities and the sardonically unconscious self-scourging of the characters themselves...The tremendous dramatic power of the specious logic with which Mrs Warren defends her course; the sardonic irony of the parting between mother and daughter!...Devastating in its consummate irony is the passage in which Mrs Warren, conventional to her heart's core, lauds her own respectability; and that in which Crofts propounds his own code of honour...Mrs Warren's Profession is not only what Brunetière would call a work of combat: it is an act of declared hostility against capitalistic society, the inertia of public opinion, the lethargy of the public conscience, and the criminality of a social order which begets such appalling social conditions. Into this play Shaw has poured all his socialistic passion for a more just and humane social order" (Henderson, 1911 pp 306-307). "Mrs Warren’s Profession reads blazingly well today, mainly through its excellent construction (it is, in its revelations, closer than many plays Shaw wrote to the well-made play) and its character-drawing. Vivie, the matter-of-fact, scholastic, “new woman” daughter, is a genuine study (Shaw admitted her smoking was based on that of the real life person on whom she was modeled) and her difference from her mother, in natural temperament, education and outlook, provides the living human conflict of the play and keeps it strongly alive. Mrs Warren herself is depicted as coarse yet full of the feeling Vivie lacks. It is the kind of feeling, fairly shallow, by which Shaw does not set great store, but nevertheless portrays with compassion and skill. It is a clever and believable study and every scene in which Mrs Warren appears has a flesh-and-blood reality" (Williamson, 1916 p 112). Goldman (1914) also appreciated the mother-daughter conflict and also the irony in comparing Mrs Warren's fate with her sister's: "no, it is not respectable to talk about these things, because respectability cannot face the truth. Yet everybody knows that the majority of women, 'if they wish to provide for themselves decently, must be good to some man that can afford to be good to them.' The only difference then between Sister Liz, the respectable girl, and Mrs Warren, is hypocrisy and legal sanction. Sister Liz uses her money to buy back her reputation from the church and society. The respectable girl uses the sanction of the church to buy a decent income legitimately, and Mrs Warren plays her game without the sanction of either. Hence she is the greatest criminal in the eyes of the world. Yet Mrs Warren is no less human than most other women. In fact, as far as her love for her daughter Vivian is concerned, she is a superior sort of mother. That her daughter may not have to face the same alternative as she,- slave in a scullery for four shillings a week- Mrs Warren surrounds the girl with comfort and ease, gives her an education, and thereby establishes between her child and herself an abyss which nothing can bridge. Few respectable mothers would do as much for their daughters. However, Mrs Warren remains the outcast, while all those who benefit by her profession, including even her daughter Vivian, move in the best circles" (pp 182-183). “Vivie Warren begins and closes the play, and Shaw reverses expectation and conventional pattern by placing the reconciliation and understanding between mother and daughter in act 2 and concluding with the child’s rejection of her parent…Vivie at the same time refuses the traditional alternative of love’s young dream in the shape of Frank Gardner” (Raby, 2004 p 200). In Mrs Warren’s profession, Shaw declared himself just such a master-hand by writing a play that deliberately reversed every convention of the fallen-woman drama. His fallen woman is not a glamorous courtesan who wears silks and jewels for three acts and then dies of consumption but a vulgar matron who wears gay blouses and brilliant hats and ends the play in robust good health. When her daughter, Vivie, a self-sufficient Cambridge graduate, learns that her mother made her living through prostitution, Mrs Warren responds not with shame and repentance but with vigorous self-justification” (Eltis, 2004 p 229).

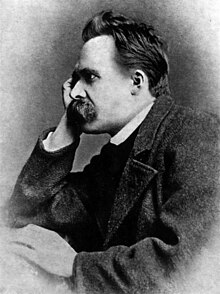

"Man and Superman" "retains its popularity as a comedy embodying humanity’s favorite theme for entertainment, the making of marriages by female will against the natural masculine instinct to escape the chains of a single, responsible relationship...Ann, for all the charm any actress can give her, is not an attractive creation, and close to satire in Shaw’s use of her uncomprisingly as a symbol of Victorian hypocrisy and a representative of feminine ruthlessness in sexual pursuit. If she showed the slightest interest in Tanner mentally, or appreciation of his work and its cost to him (for all work of his kind is costly in energy and mental peace), we might warm to her more; but actually Shaw is psychologically not unshrewd here, for frequently enough this is the kind of woman men of intelligence are basically attracted by, yield to, marry, and in a remarkable number of cases remain faithful to, even though they may sometimes secretly regret some deeper lack in the relationship. It is, of course, sex triumphant, a fact of life Shaw, despite his instinctive revulsion, was honest enough to recognize as overriding in action" (Williamson, 1916 pp 132-133). “The artistic effect of 'Man and Superman' is like that of Voltaire’s ‘Candide’, where a fundamentally serious point of view is expressed in a playful and improbable tale...Tanner is an extravert, a man entirely absorbed in his activities...an intellectual...and that is why in the end he becomes the helpless prey of Ann in her lust for marriage...He throws out bold truths, but with an undertone of skepticism” (Lamm, 1952 pp 272-273). “The joke on Tanner...is that all the time he is theorizing about the life force, he is being ensnared by it” (Brustein, 1964 p 219). "Tanner’s love of Ann is a sideline to his surrendering liberty as any philosopher should, for the purpose of perhaps breeding the first Nietzschean superman. Male critics often resent Ann Whitefield as an instance of the calculating woman, sometimes as a cold-blooded liar and hypocrite (Hobson, 1953, p 149). In Man and Superman Shaw has also stated clearly and illustrated his peculiar attitude to the relation between the sexes. The main part of the story tells how Ann driven by the Life Force, tricks Jack Tanner, the revolutionary free-thinker, into marriage. Tanner knows perfectly veil what she is about, although the poetic Octavius would still regard woman as an angel sent on from high. Poor littlo ‘Ricky-ticky-tavy’ gets the worst of it. Ann, although se may play with him as a cat plays with a mouse, wants Tanner himself and even a modern automobile with the good services of the rash driver, like Enry Straker, cannot save him. Tanner and Octavius are set in close opposition. The one is the clear-eyed modern, the other the romantic poet” (Mullik, 1956 p 49). “The real artist-creator, according to Shaw, is a match for any woman bent on creating in her own more physical way...because, like her, he has a purpose. John Tanner is a talker rather than a creator, and is, therefore, quite properly captured by Ann” (Gassner, 1954b p 158). According to MacCarthy (1907), Shaw "set out purposely to write a play in which sexual attraction should be the main interest; but in his other plays also he has always made the nature of the attraction between his characters quite clear. What is remarkable about the scenes in which this is done, is the extent to which sexual passion is isolated from all other sentiments and emotions. His lovers, instead of using the language of admiration and affection, in which this passion is so often cloaked, simply convey by their words the kind of mental tumult they are in. Sexual attraction is stripped bare of all the accessories of poetry and sympathy" (p 57). "Shaw adheres first to the principle that comedy must have a fixed vantage-point, though he transforms it to suit his own purpose. He retains, too, the prerogatives and tricks of comedy, without, however, the necessity of being chained to them. He also keeps to stock types for comic purposes, but his new social philosophy gives him a new set of types. Even in incidentals he can follow well-worn grooves of the art; the Straker-Tanner relationship in 'Man and Superman' rests on the conventional master-valet set-up, given completely new vitality from the new social background" (Peacock, 1946 p 77). “Shaw’s writing was not hobbled, as Galsworthy’s was, by the self-imposed naturalistic requirement of copying the speech of floundering characters” (Gassner, 1956 p 43). In the play, "we have Violet, a practical-minded young woman, secretly married to Hector Malone, American, whose father, a multi-millionaire, is, like all the fathers in Shaw's plays, dictatorial, testy, and in the end submissive. We have Roebuck Ramsden, Ann's guardian, an elderly Radical, rather absurd with his superannuated and romantic notions, cutting a melancholy figure beside the triumphant young people of advanced ideas, represented by Ann, Tanner, Violet, and Hector. We have Miss Ramsden, Roebuck Ramsden's sister, also testy arid full of conventions. Finally, we have Octavius, poet arid lover, scorned and made a mock of by Ann, who loves Tanner, desires him, and takes him; but this defeat of Octavius the lover is the triumph of Octavius the poet, just as the defeat of Eugene the lover in 'Candida' (1898) is the triumph of Eugene the poet" (Hamon, 1916 p 181). “Octavius Robinson...would-be poet and playwright, is a highly conventional young man, firmly embedded in the manners and mores of English upper-middle-class society. His role as a poet is largely constructed by Jack Tanner” (McDonald, 2006 p 70).

"Major Barbara" "has a first act that comes as close to the spirit of Wildean comedy as any other that Shaw ever wrote. Its witty sallies keep audiences laughing continuously; and the character of Lady Britomart, that formidable person, reminds one very much of Lady Bracknell in Wilde's The Importance of Being Earnest” (Lockhart, 1968 p 20). “Major Barbara" "revealed the master of social comedy, even if it marked no advance in content over 'Widower’s houses' (1893) with its point that tainted money is so widespread that it cannot be escaped anywhere. In a corrupted social order, everything is defiled by the same pitch, and there is no chance for individual salvation except in the cleansing of society. Cheap and easy philanthropy is as effective as painting cancer with mercurochrome. Major Barbara of the Salvation Army approaches this conclusion when she discovers that her benevolent organization receives money from distillers and munitions-makers like her father— in other words, from the very industries that produce more evil than a thousand Salvation Armies can ever cancel. Sufficiently honest to recognize a truth when she meets it, unhappy Barbara Undershaft cries out: 'My God, why hast Thou forsaken me?' and takes off her uniform. If the play marks an improvement over Shaw’s first drama, this is because Barbara is an affecting person and because the munitions-maker Andrew Undershaft is a superb character" (Gassner, 1954a pp 607-608). Shaw “can indict British capitalism and yet make the hero of his indictment an arch-capitalist like Undershaft. This is the secret of comic genius, and, at the heart of it, is common sense so resolutely pursued that it becomes startlingly uncommon sense” (Gassner, 1954b p 141). Shaw’s “first act is one of the masterpieces of drawing-room comedy. Lady Britomart (whose name from an obscure Greek divinity naturalized into English by Edmund Spenser) so trenchantly combines Britannia with a martinet, is, though an estranged, a strongly compatible wife for Undershaft. And indeed, Shaw, his evolutionist’s eye on heredity, points out that Barbara is her mother’s daughter and Sarah her father’s, though in both cases against the obvious grain. It was, however, pointedly in honour of her father’s trade that Shaw chose to call Barbara Barbara. St Barbara is the patron saint of gunners. The Undershaft marriage is the uneasy but effective alliance of capitalism and the Whig aristocracy that governed the British empire” (Brophy, 1987 p 95). “Undershaft, the arms dealer, built up as a stock sinister capitalist before his entrance, proves mild, sensitive, willing to listen to everyone...Barbara’s ‘My God, my God, why has Thou forsaken me?’ is convincingly in character...[since a] Christian...facing a spiritual crisis should echo the words most familiar to her” (Chothia, 1996 pp 161-163). "Barbara’s own realization that the helping of the poor through religious channels only scrapes the surface of the problem, and there is better work for her here in her father’s factory community, in which there is every material consideration and no spiritual fulfillment. But the decision is not arrived at without bitterness, any more than Barbara’s decision to leave the Salvation Army rather than to join them in accepting the bribe of the manufacturer of the whiskey which destroys their battle to revive human dignity....What matters theatrically is that this third act of Major Barbara- like that other long discussion scene between Warwick, Cauchon and de Stogumber in Saint Joan- has such argumentative force and wit that it habitually holds its audience’s rapt attention and therefore entertains it, in the best sense of the word, no less completely than if the dramatist were indulging in popular melodramatics. This, perhaps, has been Shaw’s greatest gift to the theatre of our time. To make an audience listen, think, and actually enjoy listening and thinking, was no mean feat after four hundred years of stage concentration on conventions far removed from thought or the real business of daily life. The gap between the literary worlds of the novel and the theatre has never been so wide since" (Williamson, 1916 pp 141-142). "Barbara Undershaft finds that the authorities of the Salvation Army are content to accept contributions from a distiller whose trade is one of the most powerful influences which they have to combat. This realization brings her world crashing about her ears; she at first feels that there is nothing left to live for. But this is only the peripeteia; as usual it is to provide a solution. Not only does this overthrow or recoil give the logical victory to her father's opposing point of view far more than that, as soon as she grows calm she discovers that her real life-work, which she had supposed inextricable from her allegiance to the Salvation Army- the work, that is, of organizing social sanity and happiness—is not in fact dependent upon that allegiance, but can survive it she goes on to perform the same task amid new surroundings" (Norwood, 1921 p 179). For Goldman (1914), the play "points to the fact that while charity and religion are supposed to minister to the poor, both institutions derive their main revenue from the poor by the perpetuation of the evils both pretend to fight. It is inevitable that the Salvation Army, like all other religious and charitable institutions, should by its very character foster cowardice and hypocrisy as a premium securing entry into heaven" (pp 186-188). In writing "Major Barbara", Shaw "is stimulating in his criticism of certain tendencies in modern philanthropy, and consistent with his own individualistic philosophy in declaiming against all who make a virtue of poverty, starvation, and humility. He announces his preference for the avowed egoism of Undershaft as opposed to the masked egoism of the converters and the converted. Yet, while proposing Undershaft as a fair example of the philanthropic captain of industry, Shaw jibes at those who would accept his benefactions and condemn, in secret, his morality" (Chandler, 1914, p 348). When Snobby Price declares: 'I'm fly enough to know wots inside the law and wots outside it; and inside it I do as the capitalists do: pinch wot I can lay me ands on. In a proper state of society I am sober, industrious and honest: in Rome, so to speak, I do as the Romans do,' Jones (1962) agreed that ”only when men are safe enough from poverty and insecurity can they afford to consider questions of morality at all” (p 67). Although Williams (1965) stated that "the emotional inadequacy of [Shaw's] plays denies him major status" (p 152), this notion is disputed. For example, in the Salvation Army scene, “the conflict of soul between Barbara and Bill is described with such sincerity that even deeply religious people have been carried away” (Lamm, 1952 p 276-277). “The appearance of the drum marks the high point of Barbara’s power as a salvanionist. The drum...catches the comedy and the seriousness of Adolphus Cusins’ devotion to Barbara and to the vital force he honors in her and in all the religions he collects. He and Barbara kiss over the drum” (Goldman, 1986 p 107), a sympathetically funny moment of discovery, at least for a 1905 audience, because the gesture can only be done with their having kissed several times before. “There is a brilliant parody of a ‘cognitio’ at the end of ‘Major Barbara’ (the fact that the hero of this play is a professor of Greek perhaps indicates an unusual affinity to the conventions of Euripides and Menander), where Undershaft is enabled to break the rule that he cannot appoint his son-in-law as successor by the fact that the son-in-law's own father married his deceased wife's sister in Australia, so that the son-in-law is his own first cousin as well as himself. It sounds complicated, but the plots of comedy often are complicated because there is something inherently absurd about complications. As the main character interest in comedy is so often focussed on the defeated characters, comedy regularly illustrates a victory of arbitrary plot over consistency of character” (Frye, 1957 p 170). "Shaw, unlike Tolstoy, is both destructive and constructive. Even by the aid of the Mammon of Unrighteousness in the person of Undershaft, his mind is vigilant and alert to point the way to better things. For when Barbara visits her father’s munition works, expecting to see a group of noisome and pestilential factories surrounded by workmen’s and labourers’ hovels and slum buildings, she finds instead clean, spick-and-span, well-lighted buildings, to which is attached a garden city with all the amenities of civilization- public library, an art gallery, a concert hall, a theatre, public and private gardens, playgrounds, baths, clubs, co-operative associations, and all that helps to make life healthy, decent, and liveable" (Balmforth, 1928 p 37). "Shaw summarizes his constructive remedies for the situation at the end of the preface to Major Barbara. They are: a just distribution of property, a humane treatment of criminals, and the return of religious creeds to intellectual honesty. These three ideals may perhaps be realized when men in an influential position adopt a platform as broad and firm as Andrew Undershaft’s true faith of an armorer. Society cannot be saved until, as Undershaft paraphrases Plato, 'the Professors of Greek take to making gunpowder or else the makers of gunpowder become professors of Greek,' and until the Major Barbaras who yearn vaguely after righteousness make up their minds to die with the colors of a faith securely founded on scientific accuracy. The power obtained through fighting may become a cult and sweep away with it the petty insecurity of halfway measures, taking with it all sense of safety and security for the average well-meaning but timid citizen of the upper middle class" (Perry, 1939 p 384).

"In this modernizing of ancient themes of [Pygmalion] and in treating ancient characters with the familiarity and lack of prejudice that one uses with contemporaries, Shaw has influenced the whole of modern literary taste and culture, and he may be considered as one of the forerunners of 'novelized' history" (Pellizzi, 1935 p 87). “In the original romance, so lyrically revived by Shaw's friend William Morris, Pygmalion marries Galatea. Might not something of the kind be possible for Shaw, since Pygmalion is a life-giver, a symbol of vitality, since in Eliza the crime of poverty has been overcome, the sin of ignorance cancelled? Or might not Higgins and Eliza be the 'artist man' and 'mother woman' discussed in 'Man and superman'? They might if Shaw actually went to work so allegorically, so abstractly, so idealistically. Actually Pygmalion: a romance stands related to romance precisely as "The devil’s disciple' stands to melodrama or 'Candida' to domestic drama. It is a serious parody, a translation into the language of 'natural history'. The primary inversion is that of Pygmalion's character. The Pygmalion of romance turns a statue into a human being. The Pygmalion of 'natural history' tries to turn a human being into a statue, tries to make of Eliza Doolittle a mechanical doll in the role of a duchess. Or rather he tries to make from one kind of doll a flower girl who cannot afford the luxury of being human another kind of doll, a duchess to whom manners are an adequate substitute for morals...If the first stage of Higgins' experiment was reached when Eliza made her faux pas before Mrs Higgins' friends, and the second when she appeared in triumph at the ball, Shaw, who does not believe in endings, sees her through two more stages in the final acts of his play, leaving her still very much in flux at the end. The third stage is rebellion. Eliza's feelings are wounded because, after the reception, Higgins does not treat her kindly, but talks of her as a guinea pig. Eliza has acquired finer feelings...The play ends with Higgins' knowingly declaring that Eliza is about to do his shopping for him despite her protestations to the contrary: a statement which actors and critics often take to mean that the pair are a Benedick and Beatrice who will marry in the end. One need not quote Shaw's own sequel to prove the contrary. The whole point of the great culminating scene is that Eliza has now become not only a person but an independent person” (pp 120-123). “It is [Higgins] who would need the intercession of a deity to be turned from marble to man” (Freedman, 1967 p 49). “England in the early decades of the 20th century was obsessed by the matter of class status, by the gradations of the rigid social structure...Shaw observes in ‘Pygmalion’ that the right accent together with the right clothes could carry the day...that class distinctions lose their force when a decent education can transform a street vendor into a ‘duchess’, that education made available to all those with the intellectual means of profiting from it would eliminate the outworn concepts of caste and class” (Goldstone, 1969 p 17). "Pygmalion is a study in the transference of an individual from one social class to another. Shaw argues that, since the capacity of speech is one of the most divine of human attributes, a person who can change the sounds made by another’s voice alters at the same time the soul to which the voice gives expression; also that a person who changes the economic status of another individual is responsible for changing his mentality. Shaw makes the latter point by introducing into Pygmalion the picturesque subsidiary character of Eliza’s father, one of the 'undeserving poor'. In his unregenerate state, he prefers not to have too much money, for fear he might acquire the damning virtue of prudence. Later, when Higgins has been accidentally instrumental in procuring £3000 a year for him, Doolittle has to adopt middle-class morality and marry the 'missus', who would not tie herself up to him for life when he was poor. Doolittle appears only twice in the play, once in each of his economic incarnations" (Perry, 1939 p 389). "Shaw chuckled over the success of his play, writing that 'it is so intensely and deliberately didactic, and its subject so dry, that I delight in throwing it at the heads of the wiseacres who repeat the parrot cry that art should never be didactic. It goes to prove my contention that art should never be anything else.' He might have noted, however, that the didacticism was largely imbedded in the Dickensian characterization of that proletarian philosopher Doolittle and in his daughter Eliza herself when she emerges in her Pygmalion's studio not only as a pseudo-duchess but as a living woman. In fact, this Galatea becomes so completely alive that she disturbs the scientific equanimity of her sculptor, who is himself a vivid personality despite the mother-fixation that deprives Higgins of the conventional qualification of sexual passion" (Gassner, 1954a p 609). In the myth, Pygmalion gives Galatea life without mating; so Henry. In some respect, he has given life to her, but Eliza’s complaint is that such a life is useless to her.

Lewisohn (1922) described "Heartbreak house" as "softer in tone than many of Shaw's plays; it is, for him, extraordinarily symbolistic in fable and structure...He saw a society divided between 'barbarism and Capua' in which 'power and culture were in separate compartments'. 'Are we,' asks the half-mythical Captain Shotover, 'are we to be kept forever in the mud by these hogs to whom the universe is nothing but a machine for greasing their bristles and filling their snouts?' His children and their friends played at love and art and even at theories of social reconstruction. Meanwhile the ship of state drifted. 'The captain is in his bunk,' Shotover declares further on, 'drinking bottled ditch-water, and the crew is gambling in the forecastle'...In the result of the symbolical air-raid he sounds a note of fine and lasting hope. The two burglars, the two practical men of business are blown to atoms. So is the parsonage. 'The poor clergyman will have to get a new house'. There is left the patient idealist who pities the poor fellows in the Zeppelin because they are driven toward death by the same evil forces; there are left those among the loiterers in Heartbreak House who are capable of a purging experience and a revolution of the soul" (pp 160-161). "The immediate result of the air raid is the death of two practical men, a burglar who acts like a man of affairs and a man of affairs who acts like a burglar. These two men have interchanged functions and between them exhibit all the characteristics of predatory capitalistic finance. The relations between Boss Mangan, the employer, and Mazzini Dunn, his employee, an earnest, incompetent 'soldier of freedom', are like those existing between organized industry and the spirit of noble optimism, which had at first hoped to be the master, not the slave, in its partnership with big business. This analogy is further carried out by Mangan's desire to marry Dunn’s daughter, Ellie, brought up by her father in financial poverty, but endowed with rich spiritual possessions in the knowledge of Shakespeare"(Perry, 1939 pp 391-392). "The greatness of this play, for all its incidental coldnesses and cruelties and comic intrusions, is its oldest inhabitant, Captain Shotover, a figure rough-hewn out of his own poop like a figurehead on the prow of a ship, a King Lear without the tragedy (though certainly with hints of pathos) and still in spite of his calculated senile absent-mindedness in full command of his kingdom and his daughters. He is a prophet thundering in navigational terms of Britain’s danger, but much more than that a prophet of war through the ages, now coming like a messenger of death, on wing, to destroy mankind...At the heart is human disillusion- the disillusion of love which finds its hardness in rebuilding a life without it, and its wisdom and resignation from the aged who have experienced all things, as Ellie does from Shotover. But there is valiancy, too, in the face of the bombs that suggests at the last the human will to survive, the life force still not spent. And in this the old Shaw thunders beneath the iridescent lightning of the future. It is his work of purest imagination, in character and vision and therefore his nearest to poetry, the highest expression of genius. By it he lives on, dispelling wisdom and warning into the future. For this is a lion of a play, with a roar to waken the sleeping conscience of every generation" (Williamson, 1916 pp 172-173). It is "a magnificent comedy of humors and a powerful symbol wrapped in whimsy. Captain Shotover’s house is a Noah’s ark where the characters gather before the flood. They and the classes they represent have been making a hopeless muddle of both society and themselves. The only half-rational Hector Hushabye and his wife display the futility of the upper classes; a British aristocrat exemplifies the bankruptcy of Britain’s rulers; the capitalist Mangan represents the predatory force of Mammon. All are equally blind to the wrath of God and to the storm they have been raising unknowingly. The innocents are helpless or they must compromise like the hard-headed poor girl who is willing to marry the capitalist for his money, and the one knowing person among them, Captain Shotover, has taken refuge in eccentricity. Then the storm breaks loose and death comes raining from the skies in an air raid. The despair in the play is manifest, for Shaw’s pity and moral earnestness did not decrease with age; the harlequinade of Heartbreak House is a Dance of Death. Still, Shaw the Fabian and one-time agitator was loath to renounce all expectation of salvation through a new order. Hope was implicit in the death of the thieves of the play who are blown to pieces by the bombardment; did not many socialists believe that predatory capitalism was finished by the war just as the capitalist Mangan was finished by a bomb! Amid the wreckage Shaw’s remaining characters try to pull themselves together. The call for courage is sounded resonantly with Shaw’s customary eloquence, as is the call for action when the antagonists of society’s malefactors declare 'we must win powers of life and death over them...They believe in themselves. When we believe in ourselves, we shall kill them'" (Gassner, 1954a p 611). Bentley (1947) pointed out that “we never learn what happens to the disillusioned antagonists of such plays as 'Candida' in which Morell is at the end crushed and speechless. In 'Heartbreak house', however, we are not allowed to remain in doubt. Ellie's peace of mind is not lasting, for she finds that ‘there seems to be nothing real in the world except my father and Shakespeare. Marcus's tigers are false; Mr Mangan's millions are false; there is nothing really strong and true about Hesione but her beautiful black hair; and Lady Utterword's is too pretty to be real. The one thing that was left to me was the Captain's seventh degree of concentration; and that turns out to be’: 'Rum,' says the captain, while Hesione confesses that her hair is dyed. The play ends with an air raid that is fatal to two members of the group. Hesione expresses the wish that the bombers will come again and Ellie, 'radiant at the prospect', cries 'Oh, I hope so!' She has been thrice disillusioned once in each act, by Hector, by Mangan, by Shotover and is, in a sense, back at the beginning again, in love with romance. Only the romance which now brings color into her life is that of a kind of warfare that threatens civilization...Ellie stumbles in disenchantment from romantic love, to 'marriage of convenience', to 'spiritual marriage', the latter gained by spirits (rum bottle) not the spirit...The story of Ellie Dunn, neatly arranged in three acts, could easily have made a personal play. But if in 'Heartbreak house' her story is the center of the action it is a center not very much more important than anything on the periphery. In the theme of the play it is the group that matters. Although the method is Chekhovian, Shaw's characters are not. Chekhov's people are felt, so to say, from the inside; they are creatures of feeling, never very far from the pathetic. Shaw's are closer to traditional puppets of comedy. They are more crudely representative of classes of men, more deliberately allegorical, than Chekhov's. Later, in 'The simpleton of the unexpected isles', Shaw would frankly state that four of his people simply represent Love, Pride, Heroism, and Empire. And it has been pointed out that the Shotover daughters and their men represent the same four forces: Hesione is Love, Ariadne is Empire, Randall Utterword is Pride, and Hector is Heroism. One might add that all the other characters 'stand for things', Mangan for business and realism, Shotover for aged intellect and that, in general, one of Shaw's worst tendencies is to create characters who have no function except to illustrate a point. The burglar episode, for instance, makes a point that is repeated in Shaw's great pamphlet imprisonment...'Heartbreak House' might be called The Nightmare of a Fabian. All Shaw's themes are in it. You might learn from it his teachings on love, religion, education, politics. But you are unlikely to do so, not only because the treatment is so brief and allusive but because the play is not an argument in their favor. It is a demonstration that they are all being disregarded or defeated. It is a picture of failure. The world belongs to the Mangans, the Utterwords, and the Hushabyes. In the world where these men wield the power stands the lonely figure of old Captain Shotover, the man of mind. What he is seeking is what Shaw has always been seeking, like Plato before him: a way of uniting wisdom and power. The Fabians had tried by 'permeation' to make the men of power wise. But the men of power preferred a world war to the world's wisdom. Shotover has given them up as hopeless. He is trying to attain power by means of mind. When he attains the 'seventh degree of concentration' he will be able to explode dynamite by mere thinking. 'A mind ray that will explode the ammunition in the belt of my adversary before he can point his gun at me' will implement thought with power" (pp 137-140).

Shaw “has widened the field and scope of the drama immensely. No other living writer has covered such an enormous area, or peopled it with such a wide variety of characters. To my sense, Mr. Shaw excels in that department more than any other present-day writer, and it is largely owing to his skill in this respect that he is able to be so extraordinarily interesting and fiercely entertaining. The way in which he says a thing is always excellent, even if the thing itself is not always sound. It always sounds sound, I admit” (Armstrong, 1913 p 320). Shaw "carries out the theory of the drama of ideas by making his play an attack upon some accepted opinion and carrying a dramatic opposition into the minds of his audience" (Moody and Lovett, 1930 pp 480-481). "Shaw’s greatest foes are sham idealism and sentimentality" (Wilson, 1937 p 242). “The seeds of Shaw's structural innovation, the discussion play, may be observed in nearly all the early works. The method of the well-made playwrights may be simply described as exposition-complication-denouement; one event leads to another until the original force has spent itself. But in the Shavian play, events exist only for the discussion they may provoke. The intellectual rather than the physical complication is the dramatist's main concern, and it is Shaw's distinction that he has made the conflict of ideas as exciting as any of Boucicault's last-minute rescues. The secret may lie in the fact that Shaw is no abstract philosopher, but one who sees ideas always as a part of human problems. The essence of Bernard Shaw is his wit, the quintessence is his humanity” (Downer, 1950 p 306). Different views have appeared regarding Shaw's dialogues. Despite possessing "an ability to make people think by making them laugh", "a kind of dramatic encyclopedism, to ridicule “persons and institutions on the principle of topsy-turvy", "a penetrating knowledge of theatrical effect", and "an Olympian indifference to conventional dramatic construction", some critics resent the author's voice in the plays, resembling "a marionette show where the master of the puppets talks all the time" (Reynolds, 1949, pp 131-132). "His amazing brilliance and fecundity of dialogue ought to have given him an immediate and lasting grip of the stage. There has probably never been a dramatist who could invest conversation with the same vivacity and point, the same combination of surprise and inevitableness that distinguishes his best work" (Mair and Ward, 1939 p 206).

“To come no later down in his career, Caesar and Bluntschli and Brassbound and John Tanner are pure figures of romance. No doubt the figures of an earlier romance exhibited their prowess in a different way. That remarkable survival, Cyrano de Bergerac, pinked his enemy to the tune of extremely acrobatic versifying. Mr Shaw’s heroes pink their opponents intellectually amid a shower of dazzling debating points. They are heroes of the intellect, perhaps, but they are romantic heroes nonetheless. They are neither conceived nor executed in a realistic attitude of mind. Mr Shaw, it should be noted, is not, like Ibsen, an innovating genius in technique; and technique being so obvious and important, this helps to conceal the magnitude of the revolution he has effected. Ibsen’s novelties were of the simple kind of which only a great revolutionary is capable. Mr Shaw is simply one of the greatest writers for the stage that ever lived. Liszt invented no new method of using the piano; but he under- stood better than any other composer how to make the technical resources of the piano effective. There is no definite method of using the stage to be set to Mr Shaw’s credit; but no dramatist has ever used the scene and the actors with greater effect. He has made such dazzling use of Ibsen’s reformed technique as almost to conceal the fact that he is moving in a quite contrary direction” (Shanks, 1923 p 201).

Shaw "was the first to fight for the free discussion of serious social problems on the English stage, and whose own plays were the native pioneers of such work" (Pearson, 1950 p 188). "No other man of letters in England since the death of Shelley was so completely devoid of a sense of guilt” (Gassner, 1954b p 148). “Mr Shaw, it seems to me, is the most versatile and cosmopolitan genius in the drama of ideas that Great Britain has yet produced...Sympathetically appreciated in the spirit of the evolutional trend of modern, even ultra-modern, drama, he is a figure of unusual significance… Just as Zola enlarged the conception of the function of the novel, sublimating it into a powerful and far reaching instrument for social and moral propagandism, so this new dramaturgic iconoclast demands the stage as an instrumentality for the exposition, diffusion and wide dissemination of his views and theories upon standards of morality, rules of conduct, codes of ethics and philosophies of life...His fundamental claim to our attention consists in his effort toward the destruction of false ideals and of the illusions which obsess the soul of man” (Henderson, 1907 pp 297-300).

Shaw’s “treatment of human relations, particularly between the sexes, strikes the audiences today as arch and intellectualized...By the time he was forty, he had managed to fabricate for himself a philosophy that seemed to synthesize a majority of the major ideas of the 19th century and tie them together so that everything came out right in the end...He persuaded himself that the world was being nudged forward by a Bergsonian ‘élan vital’, or life force, toward a higher consciousness and a more just society. Our job as responsible Shavians was to plug into this force and translate it into action...Possibly, then, it is this fundamentally jaunty belief in human progress that has lately caused students and audiences to shrug him off...Yet maybe, like Dickens, Shaw is to be considered one of those writers who transcend their own limitations. Certainly we can find elements in many of his plays that seem to go against the grain and give him a surprising thickness and ambiguity” (Gurney, 2004 pp 196-197). "Shaw’s plays will last; that in a century from now, they will appear on the stage more frequently than they do to-day; but if not, it will be because of their modernity. The very reason for their interest and applicability may be the reason for their remaining on the shelves...But if they cease to attract audiences, it is incredible that they should cease to attract readers" (Phelps, 1921 p 98).

"What first strikes us in the Shavian theatre is, perhaps, the frequency of excited scenes, of explosive arguments, violent protestations, gesticulations and agitations. Apart from the frequency of abstract discussions and the vigour of the dialogue there would be nothing very strange in this excitement, were not the passions and emotions, so violently displayed, represented as being also startlingly brief. This emphasis upon brevity of emotions is very characteristic, and one cause of the charge of cynicism which is so often brought against him. The typical scene is one in which the characters are represented in violent states of moral indignation, rage, perplexity, mortification, infatuation, despair, which subside as suddenly as they rise. The Shavian hero is a man who does not take all this hubble-bubble for more than it is worth. He preserves an exasperating good humour through it, however energetic his retorts may be, because he reckons on human nature being moved, in the long run, only by a few fundamental considerations and instincts. The hostility which he excites does not therefore trouble him the least. He counts upon the phenomenon, ultimately working in his favor, that puzzles Tanner in himself when confronted with Ann; that is, upon the contradiction between moral judgments and instinctive likings and respect. Valentine is not dismayed by Gloria's disapproval, nor Bluntschli by Raina's contempt for his lack of conventionally soldier-like qualities; both are confident that the ultimate decisions of these ladies will depend on other things. Even Tanner soon finds himself on excellent terms with Roebuck Ramsden, who began by abusing him as an infamous fellow. But it is not only the fact that the confidence of the 'realists' is always justified in the plays, which emphasizes the instability of human emotions and judgments; it is one of the fundamental assumptions with regard to human nature which lie at the back of the plays themselves. It is one of the chief causes, too, why they are regarded as fantastic; for the normal instability of emotion has hitherto found very little reflection in literature or on the stage; vacillations, flaggings, changes of mind and inconsequences of thought having been generally confined to characters intended to be obviously weak. But Mr Shaw represents, quite truly, characters of considerable firmness in many respects as subject to them" (MacCarthy, 1907 pp 53-54).

"Mrs Warren's profession"

[edit | edit source]

Time: 1900s. Place: England.

Text at http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Mrs._Warren%27s_Profession https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Mrs._Warren's_Profession

Vivie Warren, fresh from attending mathematic studies at Cambridge University, receives the visit of Praed, her mother's friend, followed by her mother along with her business-partner, Crofts, and then Vivie's friend, Frank, with his father, a rector at the local church. After being scolded for his spendthrift life by his father, Frank reminds him of his own youthful follies, including those of a sexual nature. The father is dismayed and embarrassed after finding out that Mrs Warren is Miss Vavasar, an old flame of his. Crofts has his eye on Vivie for no less than marriage, but so does Frank. Mrs Warren is compelled to explain to her daughter about her career, rising from a hotel servant to the manager of a brothel. Thinking that this refers to events of the faraway past, Vivie considers her mother "stronger than England" and shows pride at her accomplishments. The next morning, Vivie receives a marriage proposal from Crofts. Knowing the nature of his business affairs with her mother from the past and his type personnality, she unhesitatingly refuses. She then learns that the business relation between Crofts and her mother is ongoing. Angry at the refusal and smarting with jealousy towards the more favoured Frank, Crofts reveals to both that they are half-brother-and-sister. Sick of this atmosphere, Vivie suddenly leaves her mother's house to attempt earning a living on her own as an accountant. At her office, she receives the visit of Praed, intent on experiencing art in Italy, and also Frank, followed by Mrs Warren. Despite her mother's pleadings, Vivie wants nothing more to do with her and despite her friendly feelings towards Frank, she tears up the note of his declaration of love, reaching out instead for a new life dedicated to work.

"Man and superman"

[edit | edit source]

Time: 1900s. Place: England, Spain.

Text at http://www.bartleby.com/157/ https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Man_and_Superman

As a result of her father's death, Roebuck Ramsden and John Tanner are appointed as Ann Whitefield's guardians, neither of whom wanting the job, though yielding to the apparently submissive Ann. John's friend, Octavius, would like to take her off their hands by marrying her. "If it were only the first half hour’s happiness, Tavy, I would buy it for you with my last penny," John tells him. "But a lifetime of happiness! No man alive could bear it: it would be hell on earth." "It is the self-sacrificing women that sacrifice others most recklessly. Because they are unselfish, they are kind in little things. Because they have a purpose which is not their own purpose, but that of the whole universe, a man is nothing to them but an instrument of that purpose." Since Octavius intends to become a writer, a struggle may be expected. "Of all human struggles there is none so treacherous and remorseless as the struggle between the artist man and the mother woman," John continues. The two are interrupted by news of the elopement of Octavius' sister, Violet. They assume that the wedding ring she was seen to wear is false. Roebuck and Octavius agree that she should leave London, but Ann does not. "Violet is going to do the state a service; consequently she must be packed abroad like a criminal until it’s over," John wrily comments. When Violet arrives, she assures them that the ring is genuine, though she refuses to name the husband. Following a slight roadside accident in his motor car, John explains to Octavius that his chauffeur represents the new man in evolution: the polytechnic man. Octavius narrates the outcome of his marriage proposal to Ann: she wept, a dangerous sign according to John, who offers to take Ann in his car and, for the sake of social conventions, her younger sister, Rhoda, along with them. Ann objects to their submitting to social conventions. "Come with me to Marseilles and across to Algiers and to Biskra, at sixty miles an hour," John offers rhetorically. He is aghast when she accepts. An American guest of theirs, Hector, proposes to join them. John, Roebuck, and Octavius are embarrassed while explaining that such a suggestion is impossible to effect in England, since Violet is married and he is not part of the family. Hector receives this bit of news stiffly, causing further embarrassessment. When everyone leaves except Hector and Violet, she walks over to kiss him. Hector argues that they should forget about his father's objection to his marrying a middle-class English woman. "We cant afford it. You can be as romantic as you please about love, Hector; but you mustnt be romantic about money," she retorts. Meanwhile, John learns from his chauffeur that Ann's ultimate design is to marry him, not Octavius. In a garden of a villa in Granada, Spain, Hector's father, old Malone, receives by mistake an intimate note left by Violet for her husbqnd. When Malone confronts her with the meaning of the note, she deviously says that she and Hector only intend to marry. "If he marries you, he shall not have a rap from me," the irate father blares out. But Hector has enough of pretending. He informs his father of his marriage and his intention to work for a living. Malone sneers at this proposal, but when John and Octavius offer monetary help, he changes his mind. Nevertheless, Hector refuses everybody's money. Alone with Ann, Octavius declares once again he loves her. "You know that my mother is determined that I shall marry Jack," she misleadingly answers. Though seeing his depressed condition, she consoles him by saying: "A broken heart is a very pleasant complaint for a man in London if he has a comfortable income." When Anne's mother learns of Ann's comment on her wishes, she is astonished, having never formed such an idea. "But she would not say it unless she believed it. Surely you dont suspect Ann of- of deceit!" Octavius naively exclaims. But Ann believes in hypocrisy, as she tells John, who, though he loves her, too, is yet intent on resisting marriage. At the end of her resources, Ann pretends to feel faint and as the others arrive is only able to pant out: "I have promised to marry Jack." The comedy succeeds, as John would not dare humiliate her by contradicting. "What we have both done this afternoon is to renounce happiness, renounce freedom, renounce tranquility, above all, renounce the romantic possibilities of an unknown future, for the cares of a household and a family," he concludes.

"Major Barbara"

[edit | edit source]

Time: 1900s. Place: England.

Text at http://www.fullbooks.com/MAJOR-BARBARA.html https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Major_Barbara

Now that her daughters, Sarah is married to Charles and Barbara engaged to Adolphus Cusins, Lady Britomart intends to establish them on a better financial footing. She thereby invites her long-estranged husband, Andrew Undershaft, a wealthy arms dealer, to the house. Before meeting him, she explains to her son, Stephen, his family background, never spoken of before: "The Undershafts are descended from a foundling in the parish of St Andrew Undershaft in the city. That was long ago, in the reign of James the First. Well, this foundling was adopted by an armorer and gun-maker. In the course of time the foundling succeeded to the business; and from some notion of gratitude, or some vow or something, he adopted another foundling, and left the business to him. And that foundling did the same. Ever since then, the cannon business has always been left to an adopted foundling named Andrew Undershaft." Barbara works as a major in a Salvation Army shelter, where an angry Bill Walker threatens Jenny Hill for stealing his girl-friend to work for that institution. A client, Rummy Mitchens, interferes. Bill strikes his and Jenny's face, but stops of doing so to Major Barbara as an earl's grand-daughter. On learning of his daughter's benevolent endeavors, Andrew Undershaft becomes convinced that it is not her rightful place. "Barbara must belong to us, not to the Salvation Army," he declares. "Do I understand you to imply that you can buy Barbara?" Adolphus inquires. "No," he answers, "but I can buy the Salvation Army." There is much pretense surrounding that institution. One of if its members, Snobby Price, only pretends to be saved after beating his mother, and thereby attracts money from all sorts of charitable people. Mrs Barnes, a commissioner in the Salvation Army, arrives with exciting news. "Lord Saxmundham has promised us five thousand pounds...if five other gentlemen will give a thousand each to make it up to ten thousand," she reports. But since that lord is a distiller, Barbara has scruples about accepting his money. Andrew gives them the entire five. "Every convert you make is a vote against war. Yet I give you this money to help you to hasten my own commercial ruin," he announces. The gift makes Major Barbara realize her work at the Salvation Army is a sham and so she quits. On meeting her estranged husband, Lady Britomart comes down to business: "Sarah must have 800 pounds a year until Charles Lomax comes into his property. Barbara will need more, and need it permanently, because Adolphus hasn't any property." He agrees, but with respect to Stephen, tradition prevents him from making him his heir. "He knows nothing; and he thinks he knows everything. That points clearly to a political career," he remarks. The entire family is curious to visit his arms plant, Adolphus judging the place to be: "horribly, frightfully, immorally, unanswerably perfect." Indeed, he is impressed to the extent of admitting the foundling difficulty may be got over when the following is considered: "My mother is my father's deceased wife's sister," he reflects, and so consequently legal in Australia but not in England. Andrew agrees that in such a case Adolphus may indeed be considered a foundling and so liable to take his place after his death, provided he stick to his creed: "to give arms to all men who offer an honest price for them, without respect of persons or principles-" For Barbara he has this advice: "If your old religion broke down yesterday, get a newer and a better one for tomorrow." Nevertheless, Adolphus mulls over the moral dilemma of selling arms. "It is not the sale of my soul that troubles me: I have sold it too often to care about that," he says, "I have sold it for a professorship. I have sold it for an income. I have sold it to escape being imprisoned for refusing to pay taxes for hangmen's ropes and unjust wars and things that I abhor. What is all human conduct but the daily and hourly sale of our souls for trifles? What I am now selling it for is neither money nor position nor comfort, but for reality and for power." Barbara is also tempted by the job. "I have got rid of the bribe of bread. I have got rid of the bribe of heaven," she admits. Husband and wife agree with Andrew to make war on war and war on poverty. "For Major Barbara will die with the colours," she affirms.

"Pygmalion"

[edit | edit source]

Time: 1910s. Place: London, England.

Text at http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Pygmalion http://www.bartleby.com/138/

After a musical performance, the Eynsford-Hills shelter from the rain under a portico. Unable to find a cab for his mother and sister, Freddy bumps into a flower-girl, Eliza Doolittle. While she attempts to sell her flowers, Colonel Pickering enters. A bystander informs both that a suspicious-looking man is writing down everything they say. The crowd begins to grow hostile or afraid, when Pickering and Henry Higgins discover they know each other from their common interest in phonetics. Henry boasts that his teaching ability is such as to pass off the flower-girl as a duchess, creating her anew, akin to what the sculptor in antiquity did with his statue, Pygmalion. The next day, Eliza turns up to pay for speaking lessons at Professor Higgins' house, since she has ambitions to work at a flower shop, which he agrees to help her with, confident to make a duchess of "this draggle-tailed guttersnipe". He and Pickering bet on the outcome with Eliza staying at Henry's household all the while. The lesson is interrupted by the arrival of Eliza's father, Alfred, a part-time dustman and full-time drunkard, pretending to be outraged at their supposed designs on his daughter. Higgins calms him down with only a 5-pound note. Henry and Pickering make a first trial of her at the at-home day of Henry' mother, when the Eynsford-Hills are invited. Despite some awkwardness in subject and choice of expression, as when she speaks of gin as "mother's milk", Eliza, to Henry's delight, is far from the flower-girl she once was. She particularly impresses the shy Freddy. After many further sessions, Eliza is ready for the embassy ball. A Hungarian guest, Nepommuck, Higgins' first student he no longer remembers, informs the guests he has detected Eliza as a fraud, only to reveal that she is surely a Hungarian of royal blood. For this and other feats, Pickering admits that Henry has won his bet "ten times over". At Higgins' house after the ball, Pickering congratulates Henry, at which the latter scoffs, declaring the entire project a bore. As they begin to retire for the night, Eliza throws Henry's slippers at his face, for her entire life has changed, no one takes any notice of her, and now what is she to do? Without much interest, Henry suggests a few things, but seeing Eliza still sorrowful and angry, declares her to be a "heartless guttersnipe". The next morning, the two worried friends discover Eliza lodged at Mrs Higgins' house, where Alfred enters, dressed for his wedding, miserable at no longer being part of the "undeserving poor", furious at Henry for having recommended him as the "most original moralist in England", now with 3-thousand-a-year and intimidated into "middle-class morality". Eliza arrives as her frustrated father leaves with Pickering. Henry and Eliza cannot agree on continuing as they did in the past, whereupon she mentions she may accept Freddy as her husband, at which Henry laughs.

"Heartbreak house"

[edit | edit source]

Time: 1910s. Place: England.

Text at http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Heartbreak_House

Hesione Hushabye invites her friend, Ellie Dunn, at her house. No one in there household notices Ellie until Nurse Guinness eventually shows up along with Hesione's father, Captain Shotover, a captain no more, rather an eccentric inventor seeking to achieve "the seventh degree of concentration", who comes and goes unpredictably inside his own house as if in passing. Ellie confides to Hesione that she loves a man named Marcus, but out of duty to her father, Mazzini, intends to marry his boss, Mangan. Heart-broken Ellie discovers her "white Othello" to be none other than Hesione's husband, Hector, kept as a "household pet" by his wife. Ellie and Hesione are surprised by the visit of the latter's estranged sister, Lady Ariadne Utterword, aggrieved and shocked at not being recognized by either of them or by her father. The party is completed by the arrival of Boss Mangan, Mazzini, and Randall Utterword, Ariadne's brother-in-law. Alone with her in the garden, Hector flirts with Ariadne until his wife arrives, ar which point husband and wife discuss their humdrum marriage, both too cynical to be heart-broken. When speaking of her father, intent on discoveries of an undefined nature, Hesione casually mentions he keeps "dynamite and things like that" in a gravel pit. Shotover enters to discuss world affairs with Hector. The captain opines that one should kill such men as Boss Mangan and reveals his intention of discovering an engine fit to destroy all the world's armaments. Hesione flirts with Mangan, flattered by such attention, which leads him to admit to Ellie he has manipulated her father's financial affairs to obtain money from failed businesses. To his surprise, the apathetic Ellie wishes to marry him in any case. Shocked by such cynicism, he has a fit, but she hypnotizes him into sleep. When left alone in the dark, Nurse Guinness falls over him, and, when he fails to respond, thinks she has killed him. Alerted by her cries, Hesione and Ellie enter hurriedly, and, before Mangan's sleeping face, express their true opinion of the apprently heartless businessman. He starts up to reveal he had only been pretending sleep. Heart-broken, he confronts Hesione about her cruel words, at which she admits her "very bones blushed red". Suddenly, a pistol shot is heard, a burglar having been discovered upstairs. The captain blows his whistle: "All hands aloft!", he cries out, where the entire company discover the burglar to be Billy Dunn, Shotover's old acquaintance, deliberately confused by him with Mazzini Dunn, and also Nurse Guinness' estranged husband. Unheeding his pleas to get what he deserves, they refuse to hand him over to the police, but keep him in the house. Shotover agrees with Hesione that Ellie should not marry Mangan, but she, being poor, believes that to keep one's soul one must possess a considerable amount of money. Meanwhile, Randall has observed Hector's designs on Ariade and, in love with her himself, warns him to take care. When Ariadne scolds Randall for one thing or another, he breaks down weeping, broken-hearted on realizing she can never love him. In the garden at night-time, Hesione hears a "splendid drumming in the sky", an unidentified impending danger hovering over the house. The party being unconcerned by this, Ariadne and the others discuss English society. She defines two classes: "the equestrian class and the neurotic class", her tyrannical husband being the only one who can save it. The discussion becomes so personal and shameless, in Boss Mangan's view, that he starts to take his clothes off, but is prevented from going farther. When the conversation returns to Ellie's marriage prospects, she says she cannot commit bigamy, to the shock of all the company, only to say she wishes to become the captain's "white wife", considering him as her "soul's captain". The drumming in the sky gets louder. "Batten down the hatches!" the captain orders. Mangan and the robber run to hide in the gravel pit, where Shotover keeps his dynamite, into which a bomb falls, so that both are killed. "Thirty pounds of good dynamite wasted!" the captain exclaims. The nonchalant or indifferent survive the attack from above. Nevertheless, the company expect to be killed next, Hector turning on all the lights and tearing down the curtains to facilitate their end until the drumming stops, to the disappointment of Hesione, Ellie, and Hector, each hoping that the mysterious sound spelling their doom will return the following day.

Sean O'Casey

[edit | edit source]