History of Western Theatre: 17th Century to Now/Classical

The three main dramatists of the Classic or Neo-Classic period, starting at the death of King Louis XIII in 1643, are Pierre Corneille (1606-1684), Jean Racine (1639-1699), and Molière (1622-1673). In the entire corpus, several plays include adaptations of previous work. The study of adaptations is useful for detecting shifts of moods in a period or from one period to the next. “It is thanks precisely to the recurrence of identical themes in the course of several generations of playwrights that the student of literature can detect, in at least one form, the evolution of attitudes, ideals and customs. The comparison is in fact facilitated by the similarities of basic situation, for contrasts and variations between original play and its later adaptation are the more discernable for having sprung from the same set of premises” (Collins, 1966 p 22).

"The plot of the classical French drama is simpler than that of the modern romantic drama, but more complex than the ancient classical plot. The plots of Corneille and Racine hold a position intermediate between the simplicity of Aeschylus and Alfieri and the intricacy of Shakespeare and Hugo. The interest of the French classical plot lies rather in its intensity than in its complication. There is a disposition to emphasize only one supreme moment, or crisis, the action moving on unswervingly and impressively towards one grand climax, and then descending with directness and concentration to its inevitable catastro phe, more or less clearly foreseen from the first. On the whole, however, unlike the Greek and the earlier French drama, which foretells the dénouement from the beginning, the French classical drama prefers uncertainty and curiosity as to the outcome. By this means compression and economy, both of attention and of interest, are secured. This limiting of the story to one great crisis presents the exhibition of the whole of a life history or era, discourages the development of character, and excludes minor actions, irrelevant episodes, sub-plots, and parallel actions. As a result of this compression the dramatist avoids the leisurely movement of the epic and divests his action of everything that is irrelevant, digressive, or merely accessory" (Bruner, 1908 p 331).

"As the action of the Greek tragedies is always carried on in open places surrounded by the abode or symbols of majesty, so the French poets have modified their mythological materials, from a consideration of the scene, to the manners of modern courts. In a princely palace no strong emotion, no breach of social etiquette is allowable, and as in a tragedy affairs cannot always proceed with pure courtesy, every bolder deed, therefore, every act of violence, everything startling and calculated strongly to impress the senses is transacted behind the scenes, and related merely by confidants or other messengers" (Schlegel, 1846 p 256). "Their whole system of expositions, both in tragedy and in high comedy,is exceedingly erroneous. Nothing can be more ill-judged than to begin at once to instruct us without any dramatic movement. At the first drawing up of the curtain, the spectator’s attention is almost unavoidably distracted by external circumstances, his interest has not yet been excited; and this is precisely the time chosen by the poet to exact from him an earnest of undivided attention to a dry explanation,- a demand which he can hardly be supposed ready to meet...How admirable again are the expositions of Shakespeare and Calderon! At the very outset they lay hold of the imagination and when they have once gained the spectator's interest and sympathy they then bring forward the information necessary for the full understanding of the implied transactions. This means is, it is true, denied to the French tragic poets, who, if at all, are only very sparingly allowed the use of any thing calculated to make an impression on the senses, any thing like corporeal action and who, therefore, for the sake of a gradual heightening of the impression, are obliged to reserve to the last acts the little which is within their power" (Schlegel, 1846 pp 272-273).

Pierre Corneille

[edit | edit source]

After 1643, Corneille continued the strong work from the previous reign with "Rodogune" (1644).

"Rodogune" "if it did not quite reach the level of Polyeucte, was an exquisite tragedy, abounding in dramatic effect, and characterized by a greater regard for the play of intrigue than the author had previously shown. The character of Cléopatre, Queen of Syria, is one of the most terrible ever created for the stage" (Hawkins, 1884 vol 2 p 151). Although Lockert (1958) complained that Rodogune’s proposal of matricide “is entirely out of character” (p 65), this opinion comes from wanting an admirable main character to remain admirable throughout.

The play "is certainly, by virtue of the enormity of the characters, the violence of the passions, the vastness of its crimes, the most romantic of his tragedies; it is constructed with the most skilful industry; from scene to scene the emotion is intensified and heightened until the great fifth act is reached; but if by incomparable audacity the dramatist attains the ideal, it is an ideal of horror” (Dowden, 1904 p 168). “Cleopatra seizes the cup in desperation and drinks. The poison works and she is led away to die. Here is one of the few stage pictures in French classical tragedy and more action than usual on the stage. The power of the scene is undeniable. In its way it is the most striking fifth act of the century; but it helped to make Corneille exaggerate the importance of incidents and complex situations” (Stuart, 1960 p 408).

"Corneille gives full vent to his love of invention, manipulation, and theatricality. From the unorthodox exposition to the harrowing ‘coup de théâtre’ with which the play closes, Corneille assaults his spectator with shocking demands, upsetting threats, and surprising revelations...Seleucus champions an ideal whose concrete expression takes the form of non-action...Antiochus possesses the sureness of temper his brother achieves only by stages...It is he who acts constantly as a restraining force on his more tempestuous twin...He relies on entreaties and tears...When we first meet [Rodogune], she is a noble figure filled with disquiet and foreboding...At times Rodogune seems as ambitious for the crown...as Cleopatra...Rodogune is as wily as Cleopatra, but not really immoral...In demanding the twins to kill their mother, Rodogune seems to be acknowledging that circumstances force us to the choice of a non-value over a value...Circumstances will not disappoint this hope...Never once does Cleopatra express doubts as to any technique to maintain power...She is the most self-reliant of Corneille’s heroes to date, as her refusal to keep even Laonice in her confidence indicates, and she is also the most self-possessed, as the shifting developments of the last act reveal...She is an undoer of ‘natural knots’ as much as she is a weaver of ‘secret knots’...She dies unilluminated because...there are no higher powers than those of Cleopatra” (Nelson, 1963 pp 139-161).

"Rodogune"

[edit | edit source]

Time: Antiquity. Place: Syria.

Text at https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.123600

The twin brothers, Antiochus and Seleucus, are waiting for their mother, Cleopatra, queen of Syria, to reveal at last which of the two is the eldest and thereby destined to claim the throne. She has always kept this information secret to reign alone. Both brothers love Rodogune, princess of Parthia, kept a prisoner in Syria. Nevertheless, it is agreed that the elder will not only become king but also win her hand in marriage. Cleopatra hates Rodogune for having married her husband while he was imprisoned in Parthia and who had almost seized the crown from her until she killed him. Antiochus is ready to yield the crown for Rodogune's hand, but, to his grief, so is Seleucus. "She must marry, not you, not me," Antiochus concludes, "but me or you, whoever will be king." Both affirm that they are content to see their mother reign in their place, which gladdens Cleopatra, but yet she expects more from them, proclaiming that the crown belongs to whoever kills Rodogune. The brothers are astonished and silently grieve at this decision. She in turn is astonished at their silence. "Will you marry one to have her flout me," she cries,"to submit my destiny at the hands of my slave?" The brothers agree to visit the princess in prison, where Antiochus asks her to reveal the man she loves, but she refuses. "The choice you offer me belongs to the queen," she says. Seleucus warns her of the queen's hate, to be countered by choosing a husband, but she fears by choosing one to create two enemies instead of one. At last, pressed on both sides, she says she will give her hand to the man who avenges their father's murder. However, alone with Antiochus, she admits she loves him more and no longer wants to become "the prize of crime" but rather will wait to see who the queen announces as the rightful king. Antiochus reveals to his mother that they both love Rodogune. Feigning to weaken at these news, Cleopatra says: "Rodogune is yours together with the empire." But yet, alone with Seleucus, she reveals he is the eldest after all and yet might lose all. Despite his mother's wrongs against him, he answers as she wishes. "Hope to see in me but friendly feelings towards my brother and zeal for my king," he declares. Nevertheless, to continue her reign alone, she has her son killed and pretends to join Antiochus and Rodogune for the marriage ceremony. She gives Antiochus the nuptial cup, a poisoned one, but before he can put it to his lips, he receives news of his brother's murder, for which Cleopatra blames Rodogune and she Cleopatra. Antiochus hesitates about what to do, except to press the ceremony forward. As he reaches for the cup, Rodogune, suspecting poison, prevents him and asks for a servant to swallow it. Feeling caught in her own trap, Cleopatra reaches for the cup herself, drinks it, and dies. A grieving Antiochus commands that "the nuptial pomp be changed to funeral designs".

Jean Racine

[edit | edit source]

While Corneille wrote a myriad of comedies and tragedies, Racine wrote only tragedies except for "The litigants" (1668). Among Racine's most admired tragedies are "Britannicus" (1669) based on the son (41 AD- 55 AD) of Roman emperor Claudius in histories of Ancient Rome, mainly that of Tacitus (58-120 AD), “Mithridate” (Mithridates, 1673), more particularly Mithridates VI or Mithridates the Great (162-63 BC), the king of Bosphorus in Asia Minor, "Phèdre" (Phaedra, 1677), adapted from the "Hippolytus" of Euripides (480-406 BC) and the "Phaedra" of Seneca (12-65 AD), and "Athalie" (Athaliah, 1691), based on a Biblical source, 2:11 Kings. Contrary to Grein's opinion (1905, p 282), it is false that Racine is "a great orator rather than a great playwright". Among many other factors, what makes his plays intensely dramatic is the element of surprise: the characters are often startled by turn of events and each other's behavior, creating great fear and worry. A second recurrent theme is sibling rivalry, often leading to murder.

Clark (1939) pointed out that the style of "Britannicus" is of a Tacitean terseness. The character studies are striking. Indeed, Agrippina "is shown not merely as the ambitious plotter but as the mother who resents the loss of her influence over her son, not merely as the clever dialectician but as the woman liable to imprudent fits of temper...Burrhus’ virtue is mitigated by certain prudential considerations. Narcissus is a villain of a subtlety and psychological insight never before seen in drama outside of Shakespeare...Narcissus arrives with the news that preparations are complete for the poisoning of Bntannicus. Note the cool cynicism of his first speech, his quick utilization of Nero’s revised decision to enforce still more strongly his own point of view, and the short, sharp struggle with Nero’s conscience which he brings to triumphant issue by his poisonous allusion to Agrippina’s boastings" (pp 154-162). “As a single instance among many of Racine’s consummate craftsmanship in this play, we may note the scene in which Nero, concealed behind a curtain, listens to Britannicus and Junia. For tension, for terror, for sheer force and effectiveness, it can hardly be matched by any similar situation in all the dramas of the world...Derived largely from Tacitus, [the play] seems to catch something of its terse power...[Racine] meant to portray Britannicus as a high-spirited and pathetic youth; he did portray him as a little master who is at times unmanly and affected. Junia, on the other hand, is a lovely creation- of all Racine’s women the least sophisticated and, unless perhaps Monime, the most appealing- with the simplicity, the directness, the sweet dignity and the fresh charm of young girlhood...[Agrippina is more impressive as a character than Nero], for she surpasses the emperor in force of personality, intelligence, energy, and courage...The conception of the emperor...is in the main the traditional one, but not all its phases are equally stressed; that of the virtuoso, which was perhaps dominant in him, is clearly revealed only once...though at a crucial point...a young man fundamentally cruel, vain, and vicious, whose predisposition to evil at length causes him to break from restraints hitherto imposed by his weakness and timidity” (Lockert, 1958 pp 305-307). Like many others, this critic’s opinion of the portrayal of Britannicus is biased by his dislike of the courtly type, too gallant for his taste. "Nero...is portrayed with a vigour which the author often missed in his treatment of male personages, and anything more winsome and pathetic than Junie...it would not be easy to conceive. Every other important character in the play, too, is finely drawn and contrasted the fierce Agrippine...the virtuous Burrhus...the rascally Narcisse...and the generous and ingenuous Britannicus...No want of sensibility or dramatic skill was betrayed, and the diction was by far the most refined yet heard in a French tragedy" (Hawkins, 1884 vol 2 p 31). But other critics criticize the portrayal of Agrippina relative to Tacitus' portrayal. "The woman who poisoned the aged emperor, her husband, who encouraged her son in the wildest excesses of his passion, and stood not aghast at incest of the strangest sort, if so she might secure that ascendency which was slipping from her grasp, stands alone in the lurid light of a fiendish age. An imperious and dominating spirit, she formed a fitting subject for the tragedian's art. But Racine was all too weak for such an argument. His gentle and sensitive spirit shrank from the crude atrocities of his subject, and, while striving to render to the full the overweening ambition of Agrippina and the jealous haughtiness of Nero, he left in the background, or at least mitigated as much as possible, the more revolting traits" (Hallard, 1895 p 63).

The main character in “Mithridates", "with his sanguinary greatness and violent passions, more nearly accords with the conception of a tragic hero held by Shakespeare and his fellow Elizabethans than does any other protagonist of Racine...Menace lurks in his smoothest words...His indefatigable, undismayed resilience in defeat, his grandiose plans and overweening hopes of success against mighty Rome are revealed with a virile eloquence...Monime is generally considered the most attractive of Racine’s heroines, gentle and innocent though she is, she displays self-respecting pride, a quiet courage, strength of will, and devotion to duty which makes her Corneillian in Racine’s own, very different way” (Lockert, 1967 pp 356-361). "Mithridate is the tragedy of a man who feigns death to save his life, and, in an ultimate reversal, thereby loses the last little part of his life over which he has dominion. The loss is not only for one man. Neither the death of Mithridate nor the survival of Monime and Xiphares changes the tragic nature of existences that from the beginning are a kind of death in life" (Campbell, 1997 p 597). "The king treats his sons as circumspectly and defensively as he treats Monime. Despite some feeble efforts to the contrary, Mithridate displays little paternal affection for Pharnace whom he rightly suspects of treason. He usually refers to his son as 'prince', a term whose connotations are pejorative since he always calls his beloved son, Xiphares, 'my son'. Initially Mithridate shows great respect for Xiphares, but at the basis of his affection are the same considerations which prompted his anger at Monime and Pharnace: Xiphares, unlike his brother and the queen, has proven himself consistently loyal" (Cloonan, 1976 p 516). "I think that our dramatist has scarcely written anything grander than the speech of Mithridates in which he expounds his policy to his sons” (Van Laun, 1883 vol 2 p 290). "Of the four principals, Monime, who shares qualities with many of Racine's heroines, causes the least difficulty. She is a queen in name only, a prisoner of her father's promise to Mithridate, and thus resembles Andromaque. A tender victim, she is not unlike Iphigenie; a lover willing to renounce her beloved forever, she resembles Berenice...Monime is willing to do herself violence in order to fulfill her duty, and will not drop the pose of the dutiful daughter and obedient intended...Once tricked into admitting her love for Xi- phares, Monime refuses to marry Mithridate and remains unaffected by his pleas or threats...In giving up Xiphares, she consciously mutilates herself in order to carry out a duty which remains foreign to her innermost being. Her resignation is sad, not glorious" (Kuizenga, 1976 pp 281-282). “The heroine of ‘Mithridates’, the noble daughter of Ephesus, Monime, queen and slave, is an ideal of womanly love, chastity, fidelity, sacrifice, gentle, submissive, and yet capable of lofty courage. The play unites the passions of romance with a study of large political interests hardly surpassed by Corneille” (Dowden, 1904 p 213).

In "Phaedra", Racine "will closely follow Euripides in the scene where Phaedra confesses her secret to the nurse. Then he will borrow from Seneca the false rumor of Theseus’ death, for this will make Phaedra’s love for Hippolytus seem somewhat less criminal and thereby make her relax her watch over herself slightly. Besides, by putting Hippolytus in a position of power as his father’s successor, it will give an excuse for Phaedra to seek an interview with him in order to assure his protection to her own son. Finally, it will provide a sensational ‘péripétie’ in itself and pave the way for a still more striking one when Theseus returns. Then, when Phaedra has her interview with Hippolytus, he will introduce Seneca’s idea of having her blurt out a declaration of love to the latter...[The most important change in dramatic character was in Hippolytus from Euripides' chaste misogynist to a lover, which drives Phaedra's passion as it becomes] exasperated by jealousy...Phaedra takes her place with a very select few: Antigone, Lear, Faust- in the gallery of the world’s tragic portraiture" (Clark, 1939 pp 201-207). “Euripides was his chief source...He followed Seneca, however, in making Phaedra herself declare her love of Hippolytus and in making the nurse originate the slander against him...In destroying Hippolytus, [the Greek and French Phaedra] are actuated by the desire to protect their good repute and thereby their children. The Phaedra of Euripides combines this motive with resentment at the young man’s excessive abuse of her and at his failure to comprehend the agonized struggle which she has made to preserve her purity; the Phaedra of Racine, when in a revulsion of feeling she is ready to save Hippolytus at any cost, is checked by the discovery that he loves Aricia, which fills her with jealous madness and then, in consequence, with utter horror at herself and with such confusion of soul that she is paralyzed, as it were, and incapable of action until too late...The Greek Phaedra is less...the frenetic and morbid prey of her passions...[relative to] the [great] self-loathing of Racine’s Phaedra...Hippolytus must express himself like a young gentleman, with all the customary phrases of gallantry...Between what is said of Hippolytus and all that he himself says there is a hopeless incongruity...To set himself up as a judge of his father’s legitimacy and to undertake to use the power and prestige which he has gained as Theseus’ supposedly faithful son to frustrate his father’s will and despoil his father’s heir in favor of an hereditary enemy as soon as the hero-king and not unloving sire (he believed) is helpless in death, is an ugly combination of complacent self-righteousness and disloyalty...The only reason...he has for silence is that it would be unbecoming of him to offend his father’s ear with the shameful truth; and this consideration seals his lips though at the risk of his life and though his beloved Aricia, as well as he, would gain by his speaking out. But when he goes into exile, he plans to enlist friends at Argos and Sparta and make war on his country to regain his rights and Aricia’s!” (Lockert, 1958 pp 388-395). Lockert’s opinion of the portrayal of Hippolytus is biased by his dislike of the gentleman rather than the huntsman, as if the two cannot be combined in the same man. It is also a common bias for a critic to expect that a tragic victim possess no fault except the one he dies for. Hippolytus’ silence is not motivated solely to avoid offending his father’s ear but to preserve his father’s marriage and the stability of his reign. But as an exile, the right motion of a princely character is to regain what he has unjustly lost. According to Schlegel (1846), "the poet who selects an ancient mythological fable, that is, a fable connected by hallowing tradition with the religious belief of the Greeks, should transport both himself and his spectators into the spirit of antiquity; he should keep ever before our minds the simple manners of the heroic ages, with which alone such violent passions and actions arc consistent and credible; his personages should preserve that near resemblance to the gods which, from their descent, and the frequency of their immediate intercourse with them, the ancients believed them to possess; the marvellous in the Greek religion should not be purposely avoided or understated, but the imagination of the spectators should be required to surrender itself fully to the belief of it. Instead of this, however, the French poets have given to their mythological heroes and heroines the refinement of the fashionable world, and the court manners of the present day; they have, because those heroes were princes ("shepherds of the people', Homer calls them), accounted for their situations and views by the motives, of a calculating policy, and violated, in every point, not merely archaeological costume but all the costume of character. In 'Phaedra the princess is, upon the supposed death of Theseus, to be declared regent during the minority of her son. How was this compatible with the relations of the Grecian women of that day? It brings us down to the times of a Cleopatra" (p 260). “The return of Theseus radicalizes the division between extreme passion and rational duty. Phaedra denounces Hippolytus, who will not reveal the truth to his father. In Euripides, Hippolytus does not speak because he has sworn an oath of silence and does not expect to be believed in any case. In Racine, duty towards his father commends silence...Condemning him, Phaedra has acted as if Hippolytus himself stood at a passionate extreme, ready to reveal an offense to his chastity; her passion has blinded her to his moderate reasonableness” (Calarco, 1969 p 132). "In the first act of 'Phaedra', we have the scene of the avowal of her criminal love for Hippolyte, and in the fourth act the astonishing recoil of her nature on the confidante Oenone, who has dared to call in the example of the gods to palliate Phèdre's evil desires. The suggestion has gone too far, and the weak confidante has but hastened Phèdre's self-destruction" (Jourdain, 1912 p 158). "Racine represents [Phaedra] as a woman struggling with all the energy of a high and noble nature against the illicit yearnings instilled into her by Aphrodite, as loathing herself with increasing intensity as she sinks lower and lower into the abyss of guilt, as refusing to accuse Hippolyte until she has been craftily goaded to frenzy by the nurse, and finally as a prey to bitter though unavailing remorse. It was a great original conception, worked out with all the force that could be imparted to it by analytic insight, imaginative art, and beauty of diction" (Hawkins, 1884 vol 2 p 121). "One could hardly refrain from expatiating upon the delicacy and firmness of drawing in the characterization of the heroine, 'daughter of Minos and Pasiphae', the subtlety with which from the first she insinuates herself, with all the morbid fascination of her moral distemper and personal disorder, into the blood and senses of the audience. The debut of all Racine's heroines is tremendously effective- Monime's is a good instance; but Phèdre's is, in especial, insidious...Nor would a critic at large be likely to overlook the knowingness of Hippolyte's 'psychology' or the propriety of his preferences- only a novice in love would have had eyes for Aricie when Phèdre was by- nor would begrudge a word or two for Aricie herself, 'la belle ‘raisonneuse' of the salons, who takes love to be some kind of syllogism...Phèdre is not merely a sufferer and a patient; hers is the debility of innate depravity, and invalided and graceless as she is, her hapless soul is the prey of the whole passionate intrigue to which she is exposed" (Frye, 1922 pp 223-225). “The added circumstance of Hippolyte’s love for Aricie is necessary to bring out the complete conception of the character of Phèdre. This motive is not a mere sub-plot. It gives the reason for Phèdre’s silence when she knows Hippolyte is going to his doom. A passionate woman would have saved him even at the price of confessing her guilt, but a jealous woman would act as she does” (Stuart, 1960 pp 413-414). IN the description of Hippolytus' death, “Theramenes appears to deliver the messenger speech...Therames’ narrative is so vivid that we may imagine we have watched him at the moment of death. The speech is a masterpiece of dramatic narrative, morbid, powerful, self-contained" (Arnott, 1977 p 94)."The use of mythological allusion and imagery similarly provides Racine with a wealth of poetry of which few poets not even Virgil, Milton, or Keats- have availed themselves with such effective economy. Erechtheus, Minos, Pasiphae, the Cretan labyrinth and the Minotaur conjure up the atmosphere of an heroic age, when gods and men lived in closer contact, when monsters were challenged by mortals and women ravished by the gods. A new and greater dimension is afforded the play by such allusions to the myths which seventeenth-century audiences revered from their early training in classical lore" (Peyre, 1974 p 97).

"Athaliah" “is perfect in versification, finished in character-sketches, well conceived, marvelously executed, and enriched with such choruses, that though we miss the sensuous passion of his first successful play, the religious feeling so percolates the whole, without becoming obtrusive or overpowering, that I have no hesitation in calling it the most perfect of all French scriptural tragedies. It is, I imagine, also the only French tragedy, which is full of bustle and action” (Van Laun, 1883 vol 2 p 297). The play "is not only his most finished work, but I have no hesitation in declaring it to lie, of all French tragedies the one which, free from all mannerism, approaches the nearest to the grand style of the Greeks. The chorus is conceived fully in the ancient sense, though introduced in a different manner in order to suit our music, and the different arrangement of our theatre. The scene, has all the majesty of a public action, expectation, emotion, and keen agitation succeed each other, and continually rise with the progress of the drama: with a severe abstinence from all foreign matter, there is still a display of the richest variety, sometimes of sweetness, but more frequently of majesty and grandeur. The inspiration of the prophet elevates the fancy to flights of more than usual boldness. Its import is exactly what that of a religious drama ought to be: on earth, the struggle between good and evil; and in heaven the wakeful eye of providence beaming, from unapproachable glory, rays of constancy and resolution. All is animated by one breath- the poet's pious enthusiasm, of whose sincerity neither his life nor the work itself allow us a moment to doubt" (Schlegel, 1846 p 293). Racine "celebrated the salvation of the race by showing how the seed of David was preserved in the person of Joas. While the latter gives, as he should, merely the impression of a boy brought up in an ecclesiastical sanctuary, the two leading characters, Joad and Athalie, are most effective, one a Hebrew prophet, inspired to save his people and turned aside from his purpose by neither considerations of personal safety, honesty, nor the social code of manners the other, an old queen, seeking desperately to retain the power she had won by murdering her own grandchildren, vengeful and able, momentarily touched by the sight of the mysterious child she has found in the temple. To these Racine added Mathan, traitor to his religion and his race, l±e Hitler’s honorary Aryans, and Abner, the military leader who appreciates his duty to the queen, but is won over by Joad to more vital obligations. These characters, the profoundly religious inspiration of the play, the Hebraic note, mastered by Racine as by no one in France since d’Aubigné, the lyrical element in the choruses and in Joad’s prophecy, the spectacle of the temple, and the admirable structure have made many regard Athalie as Racine’s finest play, though it lacks the intense inner struggles of several of his earlier tragedies” (Lancaster, 1942 p 92). "The powerful characterization of the guilt-laden queen and of the sweet-tempered lad, the effective dialogue, and the magnificent lyrics of this tragedy create an impression of rare majesty. If some of us must find its labors academic, it is difficult to withhold one's admiration for Racine’s virtuosity or deny this work the right to be considered the greatest of all biblical plays (Gassner, 1954a p 279). "The dramatic characters are "portrayed with a sureness of touch that reveals the matured master...Abner is a very subtle study of the temporizer...Mathan makes a fine Biblical pendant to the profane Narcisse in 'Britannicus'. But the two crowning glories of the cast are, of course, the old Athalie, half queen, half witch, and her mortal foe, the priest Joad, that thundering, foaming cataract of divine fury" (Clark, 1939 pp 267-268). “The great protagonist is the Divine Being; Providence replaces the fate of the ancient drama. A child (for Racine was still an innovator in the French theatre) was the centre of the action; the interests were political or rather national, in the highest sense; the events were, formerly, the developments of inward character; but events and characters were under the presiding care of God” (Dowden, 1904 pp 216-217). “The second act...containing...the queen’s dream, her interview with the child in which with diabolical cunning she besets him with all her wiles yet is baffled at every turn by his simple innocence, her sudden outburst of fury at Jehosheba when she feels herself balked, and her marvellous revelation of her inmost heart...is the finest act that Racine every wrote...The other characters...the gentle, anxious Jehosheba, the worthy but commonplace Abner, and Mattan the arch-villain [are] delineated with sure and delicate strokes...The real protagonist...is God himself, who after suffering this blood-stained, impious woman to live long in her iniquity, at last majestically avenges the moral law upon her...It is not merely just retribution...The little Joash is the last surviving descendant of David in unbroken male succession, and it is from David’s line of kings that the promised Messiah...is to be born” (Lockert, 1958 pp 407-411). In Athaliah’s interview of the boy, “although her very life is involved, her reaction...is surprisingly tender...obviously due to the cry of blood...We begin to realize Athaliah’s tragic position. She has safety within her grasp, but her instinctive tenderness is indeed a kind of fatal blow since it prevents her from taking Mattan’s advice and have the boy killed as a precautionary measure...Athaliah, in not being able to recognize Joash until it is too late, is...a helpless victim of an inescapable superhuman persecution” (Cherpack, 1958 pp 82-84). “In his study of Athalie herself, perhaps the most unflinching portrait of moral disintegration that he ever drew, his hand had lost nothing of its cunning, and his vision had gained a new dimension of apocalyptic power“ (Speaight, 1960 p 119).

“Great art in constructing a plot; exact calculation in its arrangement; slow and successive development rather than force of conception, simple and fertile; which acts simultaneously as if by process of crystallisation around several centres in brains that are naturally dramatic; presence of mind in the remarkable skill in winding only one thread at a time; skill also in pruning and cutting down rather than power to be concise; ingenious knowledge of how to introduce and how to dismiss his personages, sometimes a crucial situation eluded either by a magniloquent speech or by the necessary absence of an embarrassing witness; in the characters nothing divergent or eccentric; all inconvenient accessory parts and antecedents suppressed; nothing, however, too bare or too monotonous, but only two or three harmonising tints on a simple background; then, in the midst of all this, passion that we have not seen born, the flood of which comes swelling on, softly foaming, and bearing you away, as it were, upon the whitened current of a beauteous river: that is Racine’s drama“ (Sainte-Beuve, 1909 edition pp 301-302).

"Britannicus"

[edit | edit source]

Time: 1st century AD. Place: Rome.

Text at http://www.archive.org/details/worksofcorneille00corn https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.186696 https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.94842

Agrippina worries over her waning influence over her son, Nero, the young emperor. She does not understand why he abducted Junie, the intended of Britannicus, his half-brother. "I would soon fear him, should he no more fear me," she admits. Nero startles a courtier, Narcissus, by declaring that he loves Junie, seeing in her a woman "beautiful without ornament, in the simple attire of a beauty torn away from sleep". In the first meeting with his captive, Nero astonishes her by declaring that he wishes to marry her, despite already being married to Octavia. Suspecting Junie's love of Britannicus, the emperor commands her to refuse him while he observes their meeting hidden behind a curtain. When Britannicus arrives, she behaves reservedly towards him, much to his distress, and Nero's, too, the first because of her apparent coldness, the second because he senses the latent fires of her love. After learning of Nero's intention to repudiate Octavia, Agrippina is incensed, and more worried than ever about her declining position. In their next meeting, as Junie explains her fake conduct to the reassured Britannicus, Nero suddenly emerges and angrily separates them, murmuring: "thus their fires are redoubled". When Agrippina at last is allowed in Nero's presence, she reminds him that he owes his position entirely to her, who, only for his sake, cast away Britannicus as ruler of the Roman empire, being the son of the previous emperor, Claudius. Assailed thus by his mother, Nero hypocritically promises to yield Junie to his rival, but when Burrhus, his tutor and a valiant soldier, enters rejoicing, he reveals his real sentiments. "I embrace my rival only to choke him," he confesses. Hearing Burrhus' pleadings for Britannicus and then Narcissus' pleadings against him, but seeking mostly freedom from his mother's influence, Nero is still uncertain about what to do. Just as Agrippina congratulates herself on her ability to restrain Nero, Burrhus runs in with the horrible news that Britannicus has been poisoned, falling "on his bed without warmth and without life". Horrified by this deed, she expects her son will live out a dire and troublesome reign. An attendant then enters to announce that Junie, renouncing the world as a vestal virgin, was restrained on her way from the world by Narcissus, at which time the people, angry at his interference, stabbed him with a "thousand blows" to the extent that "his blood besprinkled Junie". At this news, the emperor retires alone in his apartment in "fierce silence".

“Mithridates”

[edit | edit source]

Time: 63 BC. Place: Nymphaeum, Pontus.

Text at https://archive.org/details/dli.bengal.10689.15304

A short while ago, Mithridates, king of the Bosphorus and Rome’s great opponent, fell in love with Monime and offered her to be his queen in place of his wife, mother of their son, Xiphares. To avenge Mithridates’ treachery and advance Xiphares’ fortunes, the rejected woman struck a deal with Pompey the Great to overthrow the Pontine region, but was defeated by her son, whose will refuses to yield to the Roman yoke. Meantime, Xiphares has learned of Mithridates’ death, a cause of grief but also of relief, because now the way lies open to declare his own love to Monime, although now the rival of his step-brother, Pharnaces. Aware of Pharnaces’ love but unaware of Xiphares’ and unwilling to accede to it, Monime begs Xiphares to protect her. He accepts, but to her surprise, immediately declares his love for her. “Defend me from Pharnaces’ furies,” she pleads. “To make me consent, my lord, to see you afterwards, you will not need an unjust power.” Pharnaces enters to offer his own help, but Monime refuses it, because her father was killed by the Romans and she will never marry their friend. Pharnaces guesses that Xiphares has declared himself and the two step-brothers are ready to contend when, to their astonishment, the news of Mithridates’ death is proven false. The king arrives to take his wife away, but quickly discovers that she is only ready to obey, not love, supposing that she loves Pharnaces instead. To prevent Pharnaces’ plans, he commands Xiphares to protect Monime while he prepares to war against the Romans one more time. Paradoxically left together, she assures Xiphares that she in no way approves of Pharnaces’ love but his alone, “a too perfect union by fate belied!” She begs him to disobey his father only by avoiding her. To his two sons, the king reveals a bold plan: attacking Rome at their very gate, accompanied by armies from nations along the way. To add Parthia in his armies, he commands Pharnaces to marry the daughter of their king. Instead, Pharnaces proposes to appease Rome, but is interrupted by his indignant step-brother. “Burn the Capitol and turn Rome into cinders,” he cries to his father. “But it is enough for you to open the way. Deliver the fire to younger hands and, while Asia occupies Pharnaces, with that other enterprise honor my boldness.” The king approves his son’s design, except that he will accompany him, while his other son refuses his role and is arrested. On his way to a tower, he reveals that Xiphares also loves Monime. Mithridates assures Xiphares that he does not believe it, but yet he doubts. To test his future wife, the king pretends to consider himself too old and hands her over to Xiphares. After a minimal delay, she accepts, too easily in the king’s view. By the king’s behavior in disposing of the troops, Xiphares recognizes that he knows Monime’s secret. He meets Monime to say that she should save herself by marrying his father. Instead, Monime tells the king that she is unable to. Before the king can exact the widest revenge on her and his two sons, he receives news that Pharnaces has succeeded in convincing the soldiery of the futility of Mithridates’ plan against Rome, that Xiphares has joined the rebels, and that a Roman army has invaded their territory. Mithridates orders that poison be delivered to Monime. Having heard a false rumor of her lover’s death, she gladly takes it up until the king’s confidante informs her of a counter-order. After bravely fighting against the rebels and the Romans, Mithridates, surrounded by a battalion, stabbed himself with his sword, too late to be saved by Xiphares who fought “a glorious way” to his side, chasing the enemies to their vessels. Thankful of his son’s deeds, he hands Monime over to him with his dying breath. “Ah, madam, let us unite our pains,” Xiphares proposes. “And throughout the universe, let us find avengers.”

"Phaedra"

[edit | edit source]

Time: Antiquity. Place: Trezene, Peloponnesus, Greece.

Text at http://www.bartleby.com/26/3/ http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Phaedra_(Racine) http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/1977 https://archive.org/details/phaedraaclassic00racigoog https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.186696 https://archive.org/details/dli.bengal.10689.15304

Hippolytus, conscious of the presumed hate of Phaedra, his stepmother, and seeking to escape the amorous attentions of Aricia, disapproved of by his father, Theseus, intends to leave Troezen. On seeing Phaedra, he escapes immediately, while Phaedra, seeing him go, sinks under her woes, saying: "How these vain ornaments and veils press me down!" and seems to be slowly dying. Her confidente, Oenone, is unable to lift her spirits, not knowing the cause of such suffering. At last Phaedra reveals that not only does she not hate Hippolytus, but, though her stepson, she loves him all too well and culpably, for on seeing him a little after her marriage she "recognized Venus and her fires". News arrive that her husband, Theseus, has died, so that, according to Oenone, Phaedra now has all the more reason to live, since the husband's death "has cut the knots that made all the crime and horror of your fires", at which Phaedra agrees to follow her advice and live. Now that his father is presumed dead, the way is free for Hippolytus to divulge his love to Aricia, whose response is discretely favorable. As Hippolytus prepares to subdue Athens for her sake, Phaedra asks him to protect her young son. In Hippolytus she seems to see her husband once more. He is ashamed of such attentions. Despairing of her quest to make him love her, Phaedra takes away his sword and threatens to kill herself, but Hippolytus does nothing. Oenone takes the unhappy Phaedra away. Meanwhile, Athens has declared in favor of Phaedra's son as her rightful king. Despite her sufferings, Phaedra still hopes to obtain Hippolytus. She decides to yield the crown of Athens to Hippolytus. "I place under his power both son and mother," she says to Oenone. But, before speaking with Hippolytus, Oenone advises her to abandon her quest. "You must choke off the thought of such vain love," Oenone pleads, because Theseus is alive, at which Phaedra sinks into even deeper woes, expecting Hippolytus to reveal her adulterous love, or else perhaps herself will do so inadvertently. Oenone proposes that she accuse Hippolytus of incest. When Theseus enters, Phaedra suspiciously retires with her stepson's sword, saying she is "unworthy of pleasing or approaching" him. Too long inactive, Hippolytus proposes to leave and build a name for himself, worthy of his father's. Theseus is dismayed at his wife's behaviour and seeks her to find out who has played the traitor in his absence. Thinking to benefit her mistress, Oenone tells Theseus that Hippolytus is guilty of an incestuous attempt. The father curses his son by threatening to use Neptune, the sea-god, as his violent avenger. Guilt-stricken at Oenone's proceeding, Phaedra returns, but loses any scruple after learning from Theseus that Hippolytus loves Aricia. When Aricia encounters Hippolytus, she pleads that he return to his father to assure him of his innocence, but Hippolytus considers this useless, being particularly unwilling to reveal to his father Phaedra's guilt. Nevertheless, Hippolytus proposes to marry Aricia and leave for Mycaena, which she agrees to do. Theseus wants to learn more on his wife's conduct from Oenone, but is told that she has drowned herself and Phaedra is in a state of "mortal despair". As Theseus fears the worse, he learns of Hyppolytus' death: affrighted by a "formidable voice" and a "humid mountain" from which "vomited" "a furious monster" the horses of his chariot plunged forward out of control and tore the unfortunate passenger to pieces, where "dripping brambles bear the bloody remains of his hair". While Theseus grieves and prepares to accuse Phaedra, she admits her guilt under the effects of a deadly poison, whereby her husband concludes: "May so dark a deed expire with her memory."

"Athaliah"

[edit | edit source]

Time: Antiquity. Place: Jerusalem.

Text at http://www.archive.org/details/greatplaysfrenc00mattgoog https://archive.org/stream/greatplaysfrench00corn#page/n23/mode/2up https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.186696 https://archive.org/details/dli.bengal.10689.15304 http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/21967

After murdering several little children of Athaliah's son in her quest to become sole reigning sovereign, unbeknown to her, one of them, Joash, is saved by Jehoshaba, his aunt, and Jehoiada, a high priest, who nurture him to become the future king. One of the main officers of the kings of Juda, Abner, expresses to Jehoiada great fear that Athaliah will seek further revenges. But Jehoiada at this time or at any other time never loses confidence in his God. Athaliah describes a dream which deeply perturbs her, in which her mother, Jezebel, appeared, "as on the day of her death pompously arrayed", warning her to tremble that "the cruel God of the Jews does not defeat you as well". Moreover, Athaliah sees in her dream a boy plunging a sword into her breast, the very child she just saw when she was awake, in a ceremony conducted by the high priest. She demands to see that boy. When interrogated, Athaliah is charmed by Joash's manner, to the extent of offering him to live in her palace, but he refuses that honor. She consults Baal's priest, Mattan, who recommends, to Abner's horror, that they kill the boy. Mattan first speaks to Jehoshaba, then to Jehoiada, who both refuse to hand the boy over to Athaliah. Instead, Jehoiada announces to the Levites and the priests Joash's true identity as king of the Jews, and they prepare to resist Athaliah's army. Unaware of what is prepared against her, Athaliah enters the temple where she is surrounded. "Unpitying God, you alone conducted this," she cries out in despair. She is murdered along with her priest.

Molière

[edit | edit source]

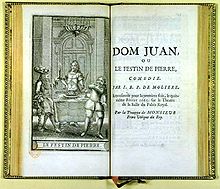

Among the universally admired comedies of Molière are "Tartuffe" (1664), "Dom Juan" (Don Juan, 1665), "Le misanthrope" (The misanthropist, 1666), "Les Femmes savantes" (The learned women, 1672), and "Le malade imaginaire" (The imaginary invalid, 1673), all characterized by sparkling wit and profound psychology.

“The mere mention of 'Tartuffe' and its acknowledged position as one of the glories and masterpieces of universal dramatic literature is a sufficient reply, one would think, to all who urge that it is not lawful to treat religion upon the stage. The play and Molière's preface to it remain as a triumphant assertion for all time of the sovereignty of the drama in its own domain. And that domain is the whole of the nature, and heart, and passions, and conduct of men” (Jones, 1895 p 54). “In no previous play had Molière shown so many interesting characters. Orgon, Tartuffe, Elmire, Donne, and Mme Pernelle are admirably presented, while the young lovers and the outbreaking son produce interesting scenes and Cléante served to protect Molière against his critics. He gives an excellent picture of a seventeenth-century household and makes other references to manners. While the structure can be criticized for admitting characters not essential to the plot and for the king’s unprepared intervention, it is admirable in its animated exposition, careful preparation, and excellent use of suspense. The scenes are varied and there are highly comic situations, especially in Acts III and IV. Molière skillfully prevented the play from becoming a drama by such devices as the concealment of Damis in a closet or of Orgon under a table. He brought it closer to life than any of his previous plays” (Lancaster, 1942 p 107). "The major dramatic question, for most of that experience, is why does Orgon worship, flatter, and bribe Tartuffe so?...The obvious answer is that Orgon, an aging man with a domineering mother, grown children, and a younger (second) wife, is seeking a way to preserve control in his household. According to this interpretation, he is obsessed less with piety than with the desire to achieve a kind of absolute power and total autonomy in the realm of his home. The instrument of Orgon’s will or desire, of course, is Tartuffe, but the ludicrous irony here is that, insofar as Tartuffe is invested with superior authority and complete independence by Orgon, the latter sacrifices his own sovereignty" (Cardullo, 2016 pp 129-130). "Orgon has the simplicity to suppose that it is the highest wisdom to devote one’s attention to a spiritual director and to neglect the ordinary affairs of everyday life. He is so blinded by his infatuation for Tartuffe that he opposes the common sense of the other members of his family, the first domestic circle that Molière had used as a dramatic background...The brother-in-law is the spokesman or raisonneur of the piece. Like Clirysalde in The School for Wives, he combats the protagonist in exaggerated terms that border on cynicism; like Ariste in The School for Husbands, he expresses Molière’s ideal philosophy of the golden mean. He oscillates between being a freethinker and a true 'dévot'. In both characters he provides the intellectual opposition to Orgon’s foolish credulity. The maidservant represents the same point of view in a less consciously critical way but with more healthy vividness. Orgon’s wife, like the Queen in Hamlet, is of a sluggish disposition, which fits into her contradictory part as the recipient of Tartuffe’s attentions and the means of his eventual detection. Orgon’s son has a fiery nature, which drives Orgon to disinherit his family in favor of Tartuffe, and his daughter’s docility does nothing to stem the tide of her father’s blind obstinacy. Orgon’s weakness so far delivers him into Tartuffe’s hands that, even when his entire family is united against the intruder, he can do nothing to protect his property and his person, until royal intervention pronounces Tartuffe a notable traitor. Then the villain is routed and the dupe is cured of his folly in a play which is more substantially dramatic than a comedy of manners usually is and which is perhaps the most effective stage piece that Molière ever wrote" (Perry, 1939 pp 167-168). Molière "seizes upon two or three salient qualities in a character and then uses all his art to impress them indelibly upon our minds...Tartuffe... displays three qualities, and three only religious hypocrisy, lasciviousness, and the love of power; and there is not a word that he utters which is not impregnated with one or all of these" (Strachey, 1964 pp 59-60). "Orgon lives in the illusion that God has sent Tartuffe as a sign of his special mercy" (Fischer-Lichte, 2002). Orgon has suffered financial and social failures and, as a result, is all the more vulnerable to be fooled by a man who purports to help him succeed at least in the after-life. "In proportion as the vision of the reader is clearer as to the abominable hypocrisy of Tartuffe, so much the more comic becomes his dupe and foil Orgon. Each subtle victory of Tartuffe, as in the case of the donation, makes the gullibility of Orgon plainer; and the play gains tense interest not merely from the conflict of inclinations in Tartuffe, but from the almost reckless way in which the action swerves and plunges from farce to tragedy and back again. It is a breathless struggle of emotions” (Jourdain, 1912 p 129). The ending of ‘Tartuffe’ has been described as a "deus ex machina" despite being incited by Tartuffe himself. “The infatuated Orgon has made him a donation, a legal engagement disinheriting his son and assigning all his possessions to Tartuffe. In addition, he has entrusted him as his director of conscience with some politically compromising documents left in his keeping by a friend...Hypocrisy is not ridiculous...His hypocrisy would have paid off...if he had not gone one step too far and denounced Orgon to the police, so provoking the royal intervention...The principal object of laughter is the dupe...Obsessive religion leads to pernicious results” (Brereton, 1977 pp 118-120). “The disinheritance of Damis marks an important point of transition from the regular comic obstacle of the tyrannic father blocking the young people’s marriage toward a more wide-reaching disorder...The deed of gift and the coffer is entirely in line with the way in which the hypocrite rides the unpredictable waves of events in the play…it follows the escalating gravity by which Tartuffe’s power spreads outward from the single bourgeois family to society as a whole” (Grene, 1980 pp 157-159). “Tartuffe, who ought to be bound to Orgon by the strongest ties of gratitude, allows the son to be turned out of the house by his father, because the latter will not believe the accusations brought against the hypocrite- tries to seduce his benefactor's wife, to marry his daughter by a first marriage; and finally, after having obtained all his dupe's property, betrays him to the king as a criminal against the state. The conclusion of the play is that Tartuffe himself is led to prison, and that vice is for the nonce punished on the stage as it deserves to be” (Van Laun, 1883 vol 2 p 207). “Orgon...tyrannizes his family but is incapable of dominating his servant. Though quick-tempered, sentimental, and impractical, he emerges from his experience a chastened and loyal husband, father, and citizen. Dorine, a clever servant who has more common sense than her master, is quick to correct mistaken judgments, whether Orgon’s or Madame Pernelle’s. Elmire, always levelheaded and good-hearted, exposes Tartuffe without usurping her husband’s authority. At the end, she does not blame Orgon for their predicament, but dutifully faces their seemingly inevitable demise. Cléante is Molière’s ‘raisonneur’...comments upon the moral of each situation and points out the distinction between a truly religious person and a pretentious imposter” (Grace, 1973 p 22). "Molière is studiously careful not only to make it clear that Tartuffe himself is a villain in disguise, but to supply an antidote to any mischief which the cause of religion might suffer from his villany, by introducing the character of Cléante into the piece. Cléante is good in himself, and he is made the vehicle of some of the noblest sentiments with regard to true religion that are to be found in any dramatic writer...When Orgon discovers the villainy of Tartuffe and rages not only against him, but against all 'gens de bien' [fine people], Cléante interposes with some words of moderation, warns him against confounding, the truly good with the impostors, and ends by telling him that to turn against the zeal because he had been taken in by a false zealot would be the worse fault of the two...The little sketch of Madame Pernelle, Orgon's mother, is excellent, and is probably not overdrawn. Elmire, the wife, is a model of prudence, and one sees in her the family likeness to her brother Cléante. She is perhaps a trifle too prudent on one or two occasions, when she might as well have spoken out more plainly. Damis, the hot-headed young son, is a good character; and the daughter, Mariane, is a capital specimen of a missy young lady. The scene between her and her lover, Valère, when the question of her marrying Tartuffe is under consideration, is one of the most amusing that Molière ever wrote... Doreen...has all the ready wit and the keen sense of the ludicrous which distingish the servants in other plays; but she has, withal, something of a higher tone than most of them, and one looks upon her as almost the good angel of the piece, opposed to the fiendish Tartuffe" (Northcote, 1887 pp 395-400). “Tartuffe, is at once sinister and comic. But it is the comic side that is first presented to us...The contrast between his florid appearance and his profession of saintliness, between his gluttony and his ostentatious piety, Is of the essence of comedy...Even in the scene with Orgon, when Tartuffe's hypocrisy begins to be more apparent, the note of comedy, even of farce, is reintroduced by Tartuffe and Orgon simultaneously plumping down on their knees...Even in the second scene with Elmire, the comic element is sustained by the presence of Orgon under the table...It is not till the last verse of all that Tartuffe becomes terrible and then only for a brief moment, for he has no sooner called upon the officer to arrest Orgon than he is himself arrested, and his power for evil is crushed for ever. But if Tartuffe is a character of comedy, if on the whole he inspires ridicule rather than terror, we must not forget that beneath his mask he is a sinister scoundrel...Orgon abandons all human affections and is wrapped up in the contemplation of heaven. Yet this change has not improved his character. He is rude to his brother-in-Iaw, tyrannical his daughter, insoIent to his wife. He turns his son out of doors and finally disinherits his whole family in favour of Tartuffe...As for Elmire...it is evident that her marriage with a rich widower who had two children was dictated by reason rather than by love. But she is a thoroughly virtuous woman, she is a good wife and stepmother, and she is even respectful and conciliatory to her disagreeable mother-in-law. In character, she is gentle and easy-tempered, kind and compassionate, averse to family jars and disturbances. According to her mother-in-law, she is fond of spending money, especially on her clothes, and though she does not court admiration, she smiles at it indulgently when it comes her way. It is the only possible character that could have fitted in with the part she has to play. Had she been in love with her husband, Tartuffe would never have made his declaration. Had she not been of a placid temperament, she would never have proposed, much less have carried out, the stratagem which at last opens her husband’s eyes” (Tilley, 1921 pp 108-120). "While Orgon and his mother are besotted by the gross pretensions of the hypocrite, while the young people contend for the honest joy of life, the voice of philosophic wisdom is heard through the sagacious Cléante and that of frank good sense through the waiting-maid, Dorine" (Dowden, 1904 pp 202-203). "In a comic repetition of words we generally find two terms: a repressed feeling which goes off like a spring and an idea that delights in repressing the feeling anew. When Dorine is telling Orgon of his wife's illness, and the latter continually interrupts him with inquiries as to the health of Tartuffe, the question: 'And Tartuffe?' repeated every few moments affords us the distinct sensation of a spring being released. This spring Dorine delights in pushing back, each time she resumes her account of Elmire's illness" (Bergson, 1913 pp 73-74). “Instead of concentrating our attention on actions, comedy directs it rather to gestures. By gestures we here mean the attitudes, the movements and even the language by which a mental state expresses itself outwardly without any aim or profit, from no other cause than a kind of inner itching. Gesture, thus defined, is profoundly different from action. Action is intentional or, at any rate, conscious gesture slips out unawares, it is automatic. In action, the entire person is engaged; in gesture, an isolated part of the person is expressed, unknown to, or at least apart from, the whole of the personality. Lastly- and here is the essential point- action is in exact proportion to the feeling that inspires it: the one gradually passes into the other, so that we may allow our sympathy or our aversion to glide along the line running from feeling to action and become increasingly interested. About gesture, however, there is something explosive, which awakes our sensibility when on the point of being lulled to sleep and, by thus rousing us up, prevents our taking matters seriously. Thus, as soon as our attention is fixed on gesture and not on action, we are in the realm of comedy. Did we merely take his actions into account, Tartuffe would belong to drama: it is only when we take his gestures into consideration that we find him comic. You may remember how he comes on to the stage with the words: ‘Laurent, lock up my hairshirt and my scourge’. He knows Dorine is listening to him, but doubtless he would say the same if she were not there. He enters so thoroughly into the role of a hypocrite that he plays it almost sincerely” (Bergson, 1913 pp 143-144).

"Don Juan" “has many fine qualities: the portrayal of the protagonist, a seducer, slayer, and atheist, constantly in search of new sensations, the celebrated peasant scenes of the second act, the only one that seems quite finished; the presentation of bourgeois Dimanche, thrifty and obsequious, and the observations of humorous, cowardly, and orthodox Sganarelle, constantly contrasting with his master and commenting comically upon his views and deeds. Mobility, bourgeois, and peasants appear. The re are references to costume, meals, and the monastic system. The supernatural element, reduced to a minimum, adds a touch of spectacle and is given a comic flavor by the valet’s reaction to his master’s death” (Lancaster, 1942 p 108). “The subject...is religion, contemptuously attacked by Don Juan and defended by his servant with conspicuous feebleness...[Juan also criticizes medicine]. As the doctors are frauds when they claim to cure physical ills, so are the priests in the spiritual domain...[Molière] entrusted the defense of religion to a buffoon, whose heart may have been in the right place but whose brain was not...[Juan], a monster of wickedness, defiant to the last, going down to his punishment...in which few audiences could have believed in this primitive spectacular form” (Brereton, 1977 pp 126-130). The latter comment is doubtful, as the view that “the end is comical...because Juan has not engaged our sympathy (Mander, 1973 p 104), which runs counter to the Christian and humanitarian view of Juan's story serving as a terrible example. Likewise, Gassner (1954a) interpreted the ending of "Don Juan" as "comic", mistakenly taking Sganarelle's lack of feeling as a sign of how the reader should respond. Nevertheless, Gassner finely observed that "Don Juan’s cynicism was illuminated with brilliant flashes of wit. In comparison with his clever sallies, his servant's commonplace precepts sound like parodies on conventional morality" (p 296). “At the end of the first act, Don Juan, first by the report of his servant, then by his own words, and finally by his own deeds, is revealed to us as an odious figure, debauched, arrogant, treacherous, and cruel, and without a single quality to relieve the blackness of the picture...In the third act, he appears as a complete disbeliever in everything supernatural...[In scenes 3 and 4, Don Juan at last displays some nobility of character. He has at any rate the physical courage and the sentiment of honour where men are concerned, without which he would not have been a true picture of his class, and which contrast so forcibly with the incomparable cowardice of his conduct to Elvire...In the 5th scene, Don Juan and Sganarelle come upon the commander's tomb, and Don Juan's complete disbelief in the supernatural is symbolised by his refusal to credit the evidence of his senses, when the statue lowers its head in acceptation of the invitation to supper...[In act 4 scene 6], the hardness of his heart is even more clearly revealed in the Sixth Scene, when his deserted wife, Donna Elvire, reappears, and after declaring that her earthly passion for him, and her anger at his desertion have given place to a pure and disinterested tenderness, warns him that the wrath of Heaven is about to fall on his head, and implores him to repent before it is too late…[In act 5 scene 1, Juan] plays the hypocrite with his father and in [scene 2], he expounds the advantages of hypocrisy to Sganarelle...The cup of Don Juan's iniquity is now full, but he receives another supernatural warning in the shape of a spectre. Again he rejects it...Sganarelle, as the minister of his master's pleasures, is in a sort of confidential position, and it is perfectly natural that, disapproving as he does, of his conduct and opinions, he should venture on some timid remonstrances” (Tilley, 1921 pp 137-150). “Don Juan is the embodiment of primitive sexual instinct, selfish, lawless, and corrupting. Advancing civilization has found it needful to control this instinct; and the insatiable seducer has come under the ban of morals and of religion which certifies morality. And therefore Don Juan is moved in his turn to scout religion and to see only hypocrisy in any manifestation of morality. He has shifting caprices and perverted desires, but his ingrained selfishness keeps him cold to the sufferings of his victims, perhaps it even leads him to find a voluptuous satisfaction in their writhings. His amorous egotism, joying in the dexterity of his devices, leads him to be proud of his inconstancy and to hold it as an element of his superiority over the rest of men…The dramatist lent to his frightful yet fascinating hero the finer qualities which belong to the type; and his Don Juan is no mere butterfly wooer of maid, wife, and widow; he is gay and clever, quick-witted and sharp-tongued. Above all he is brave; this much at least must be counted to his credit, that he is devoid of fear. A type of essential energy could not be a coward; and Don Juan has a bravura bravery. He displays an unconquerable courage in the face of death and in the presence of damnation. He has a final impenitence in view of eternity which may lend to him for the moment a likeness to Milton's Satan…Sganarelle…is a cowardly servant endowed with penetrating shrewdness. He has the hard-headed simplicity of Sancho Panza; and it is he who acts as chorus, and serves as the mouthpiece of the author. His duty it is not only to enliven the action by his blunders and by his jests but also to comment on what takes place, and to suggest to the spectators the repugnance which they ought to feel for the externally charming hero, so handsome and so brave, so cruel and so callous. It is Sganarelle who brings out the moral again and again in the course of the action. Rarely has the morality of a play been confided to a character to whom we more willingly listen, for all that he is timorous, mendacious, and servile” (Matthews, 1910b pp 262-264). “In Don Juan, whose valet, Sganarelle, is the faithful critic of his master- the dramatist presented one whose cynical incredulity and scorn of all religion are united with the most complete moral licence; but hypocrisy is the fashion of the day, and Don Juan in sheer effrontery will invest himself for an hour in the robe of a penitent. Atheist and libertine as he is, there is a certain glamour of reckless courage about the figure of his hero, recreated by Molière from a favourite model of Spanish origin” (Dowden, 1904 p 203). "To Molière [Don Juan] stood not so much for the universal lover as he stood to Mozart and Byron as for the libertine of the Regency, for the brother or cousin of Esprit de Modene, of Cyrano de Bergerac, or, with less of intellect and conduct in Don Juan, of Saint-Evremond. But the type is perennial. The baleful super-man who preys on man and woman alike, and whose one redeeming quality, such as it is, is courage that creature belongs to all time" (Marzals, 1906 pp 74-75). Don Juan's "speeches are invariably in the spirit of his actions; he leaves us in no doubt as to the principles by which his conduct is governed; he lays bare the primary anatomy of his soul; he believes nothing, hopes nothing, fears nothing, and insolently proclaims his want of faith in the efficacy of prayer. In...meeting a mendicant who passes his life in prayer, but who is dying of starvation, he tosses him a louis d'or 'for the sake of humanity'. Moreover, he is superbly indifferent to all moral considerations; he is unmoved by the anguish of the too-credulous beings whose lives he has wrecked, and is perpetually on the watch for what he terms fresh conquests...Throughout the play Don Juan is never permitted to enlist our sympathies. His courage, his esprit, his elegant and chivalrous bearing these and other natural or acquired graces- are attributed to him simply to bring his character within the bounds of humanity, to account for the fascinations he exercises over women, and to deepen, by force of contrast, the moral blackness which they appear to relieve. In this portraiture, the most philosophical yet witnessed on the French stage, the genius of Molière probably found its loftiest and most artistic expression"(Bates, 1913 vol 7 French drama pp 190-192). “Elvire is Don Juan’s opposite. She is oriented towards permanence and exclusiveness, while he has given himself over to the moment and to change. Elvire lives in a state of continual discord between strictures (social or religious) and passion (physical or emotional). Juan rejects the one and atomizes the other by dividing his passion” (Mander, 1973 p 109). The scene with the poor man has been found disturbing. ”The special credit of the poor man with heaven which makes his prayers for the charitable a suitable exchange for alms is called in question by his miserable state of necessity. How, says Don Juan ironically, can a man who spends his life praying to heaven be anything but prosperous?...It can be seen...as a rallying cry of humanism against the tyrannies of religion...The whole comic mechanism of the play depends on our delight in Sganarelle’s repeated defeat in argument...Yet finally a direct representative of the heaven, which we have been inclined to see as an unreal menace set up by self-interested parties, does indeed wreak vengeance on the sinner...[to] leave us with an ideological vacuum” (Grene, 1980 pp 179-180). But the notion that hell is “an unreal menace” rounds counter to what the audience sees.