Exercise as it relates to Disease/Does aerobic exercise improve quality of life in people with multiple sclerosis?

This is a critique of the article "Impact of aerobic training on fitness and quality of life in multiple sclerosis" by Petajan et al., published in 1996.[1]

What is the background to this research?

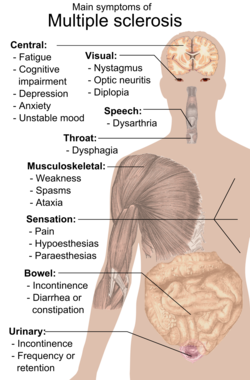

[edit | edit source]Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an incurable autoimmune disease that effects the central nervous system. In MS, the person's immune system attacks their nerves, damaging the myelin sheath (fatty outer layer) of the nerve cells and causing scarring.[2] This causes the nerves to not work properly, resulting in symptoms such as poor motor control, pain, heat dissipation problems, muscle weakness, cognitive issues, and mental health problems.[3] Exercise can improve cognition,[4][5][6] mental health[7] and quality of life[8][9][10][11] in many populations. However, at the time of this study, the safety, and effects of moderate-intensity aerobic exercise in people with MS had not been well researched.[1]

Multiple sclerosis effects more than two million people worldwide.[2] Given that MS is incurable, highly prevalent and can significantly affect quality of life, it is incredibly important to find ways to manage MS symptoms.

Where is the research from?

[edit | edit source]This research was conducted in the USA. The study was supported by a grant from the National Multiple Sclerosis Society. The study also involved two fellowships from the Jimmie Heuga Center,[1] now known as Can Do Multiple Sclerosis.

The article was published in “Annals of Neurology”, which is a high-quality, peer-reviewed journal. Annals of Neurology is ranked 6th out of 378 neurology journals.[12] This ranking is based on the number of citations the journals have and the journal's prestige.

The lead author of this paper, Jack H. Petajan, was a highly regarded neurology researcher, with over 30 years of experience.[13] Petajan has over 100 publications in this field and an h-index of 28, which is considered very good.[14] The other main authors were less established at the time of publication, but also have an interest in MS.[15][16]

What kind of research was this?

[edit | edit source]

This study is level 1 evidence[17] and a randomized control trial (RCT). RCT's involve randomly assigning participants to either a non-intervention, “control” group or an intervention group. After the intervention, the groups are compared to see if the intervention had a significant effect. RCTs are considered the best primary original research method for finding causality.[18]

What did the research involve?

[edit | edit source]The study involved 46 inactive adults with MS. They each had a Kurtzke Expanded Disability Status Scale score of ≤6 (indicating mild-moderate disability) and no other conditions that prevented them from exercising. The participants were randomly assigned to either a control group or an exercise group. The control group did not change their exercise habits during the study. The exercise group completed 15 weeks of supervised, moderate-intensity (60% VO2max) aerobic exercise. The exercise was completed three times per week and went for 40 minutes each session,[1] which is sufficient for producing a training response.[19] Physical, psychosocial and psychological measurements were taken before, during and after the intervention.[1]

Research Strengths

[edit | edit source]- Randomized control trial.

- The neurologist conducting the disability tests did not know participants’ groups, which helps remove bias.[20]

- Objective exercise intensity was adjusted as VO2max improved. This was necessary to maintain relative exercise intensity at 60% of VO2max for the duration of the study, since VO2max can change significantly in a few weeks of training.[21]

- Adherence was excellent.

- The supervised training may have increased adherence and correct exercise performance.[22]

Research Limitations

[edit | edit source]- Non-blinded participants and the use of self-report questionnaires increases the likelihood of bias.[20]

- Different exercise testing protocols were used based upon the participants’ work capacity. The validity, accuracy and comparability of these tests was not determined. This means variation within the results may have occurred due to varying validity and accuracy of testing protocols.

- External MS treatments the participants may have been receiving were not considered. External treatments should have been accounted for between the two groups, to prevent confounding.[23][24]

- The rate of symptom exacerbation was too small to determine whether there were significant differences in symptom exacerbation between the control group and the exercise group.[1]

- The exercise intervention was completed in small groups. Strong social connection is associated with increased mental wellbeing in people with multiple sclerosis.[25][26] This makes it impossible to distinguish whether the psychological benefits observed in this study were due to the social connection the intervention group experienced or the exercise itself.

What were the basic results?

[edit | edit source]Important results from this study include

[edit | edit source]- No significant changes in the Expanded Disability Status Scale or Incapacity Status Scale throughout the intervention.

- VO2max, physical work capacity and strength increased significantly in the exercise group but not the control group.

- Improved depression, anger, fatigue, social interaction, and emotional behavior in exercise group but not the control group.

- Exercise group significantly improved their Sickness Impact Profile score in the physical dimension (i.e. improved ambulation, mobility, and body care and movement).

- Positive correlations were found between changes in VO2max and improved physical and psychological scores in several assessments.[1]

The implications of these results were slightly overstated, given the limitations of this study. However, each of the implications proposed by the researchers is supported by the data they collected, so there is moderate evidence for their conclusions.

What conclusions can we take from this research?

[edit | edit source]Overall, this study provides modest evidence that moderate-intensity aerobic exercise, performed in small groups can benefit the physical, social and psychological health of people with mild-to-moderate MS. These findings are supported by more recent research.[27][28][29][30] Exercising at an intensity that improves aerobic fitness may be particularly beneficial, considering the association between maximum oxygen uptake increases and psychological improvements. However, further investigation is needed to understand this relationship better. It also remains unclear how much influence the exercise group's social interaction had on the results. However, newer research suggests exercise improves quality of life in people with MS, even when social support is accounted for.[31] This study suggests that moderate-intensity exercise is probably a safe treatment for managing MS symptoms in most people. However, whether exercise increases the risk of symptom exacerbation was unclear. Recent research has confirmed the low risk of symptom exacerbation from aerobic exercise in people with MS.[32]

Practical advice

[edit | edit source]People with MS should be encouraged to regularly engage in moderate-intensity, aerobic exercise. Exercising three times per week, for 40 minutes each session is sufficient to improve physical, psychological and social wellbeing in this population. Guidelines for exercising with MS are available from the National Center on Health, Physical Activity and Disability. Exercise programming for people with MS should consider the individual's symptoms (e.g. motor control and heat dissipation) to keep the exercise safe and enjoyable. Individuals with MS should consult a doctor or exercise physiologist before starting a new exercise regime.

Further information/resources

[edit | edit source]For further information please visit the websites below:

- Exercising with MS information, guidance and barriers: https://www.msaustralia.org.au/living-with-ms/expert-blog/exercise-and-ms

- Exercising with MS tips, activities and demonstration videos: https://www.nationalmssociety.org/Living-Well-With-MS/Diet-Exercise-Healthy-Behaviors/Exercise

- Guidelines for exercising with MS: https://www.nchpad.org/70/520/Multiple~Sclerosis

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ a b c d e f g JH. Petajan, E Gappmaier, AT. White, MK. Spencer, L Mino, and RW. Hicks. Impact of Aerobic Training on Fitness and Quality of Life in Multiple Sclerosis. Published 1996. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/ana.410390405?sid=nlm%3Apubmed

- ↑ a b Brain Foundation. Multiple Sclerosis. Reviewed 2018. Available from: https://brainfoundation.org.au/disorders/multiple-sclerosis/

- ↑ MS Australia. Symptoms. Published n.d. Available from: https://www.msaustralia.org.au/about-ms/symptoms

- ↑ YK Chang, JD Labban, JI Gapin, JL Etnier. The effects of acute exercise on cognitive performance: A meta-analysis. Published 2012. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2012.02.068

- ↑ H Cai, G Li, S Hua, Y Liu, L Chen. Effect of exercise on cognitive function in chronic disease patients: a meta-analysis and systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Published 2017. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5436795/

- ↑ JM Northey, N Cherbuin, KL Pumpa, DJ Smee, B Rattray. Exercise interventions for cognitive function in adults older than 50: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Published 2017. Available from: https://bjsm.bmj.com/content/52/3/154

- ↑ S Rosenbaum, A Tiedemann, C Sherrington, J Curtis, PB Ward. Physical Activity Interventions for People With Mental Illness: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Published 2014. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24813261/

- ↑ M Dauwan, MJH. Begemann, MIE. Slot, EHM. Lee, P Scheltens, IEC. Sommer. Physical exercise improves quality of life, depressive symptoms, and cognition across chronic brain disorders: a transdiagnostic systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Published 2019. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00415-019-09493-9

- ↑ MD Chen, JH Rimmer. Effects of Exercise on Quality of Life in Stroke Survivors. Published 2011. Available from: https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.607747

- ↑ LM.Buffartab, J Kaltera, MG.Sweegers, KS Courney, RU Newton, NK Aaronson, PB Jacobsen, AN May, DA Galvão, MJ Chinapaw, K Steindorf, ML Irwin, MM Stuiver, S Hayes, KA Griffith, A Lucia, I Mesters, E Weert, H Knoop, MM Goedendorp, N Mutrie, AJ Daley, A McConnachie, M Bohus, L Thorsen, K Schulzy, CE Short, EL James, RC Plotnikoff, G Arbane, ME Schmidt, K Potthoff, M Beurden, HS Oldenburg, GS Sonke, WH Hartene, R Garrod, KH Schmitz, KM Winters-Stone, MJ Velthuis, DR Taaffe, W Mechelen, M Kersten, F Nollet, J Wenzel, J Wiskemann, IM Verdonck-de Leeuw, J Brug. Effects and moderators of exercise on quality of life and physical function in patients with cancer: An individual patient data meta-analysis of 34 RCTs. Published 2017. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0305737216301359

- ↑ SR Cramer, DC Nieman, JW Lee. The effects of moderate exercise training on psychological well-being and mood state in women. Published 1990. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/002239999190039Q

- ↑ Scimago Journal and Country Rank. Neurology Journal Rankings. Published 2019. Available from: https://www.scimagojr.com/journalrank.php?category=2728

- ↑ The University of Utah. Internationally regarded U of U Neurologist, Jack H Petajan, dies of cancer. Published 2005. Available from: https://healthcare.utah.edu/publicaffairs/news/archive/2005/news_21.php#:~:text=6%3A00%20PM-,Jack,Petajan%2C%20M.D.%2C%20Ph.&text=Petajan%20came%20to%20the%20University,teacher%20throughout%20his%20long%20career.

- ↑ Semantic Scholar. J. Petajan. Published n.d. Available from: https://www.semanticscholar.org/author/J.-Petajan/3510711

- ↑ ResearchGate. Eduard Gappmaier. Published n.d. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Eduard_Gappmaier

- ↑ University of Utah. Andrew T White, PHD. Published n.d. Available from: https://faculty.utah.edu/u0029740-ANDREA_T_WHITE,_PhD/hm/index.hml

- ↑ PB Burns, RJ Rohrich, KC Chung. The Levels of Evidence and their role in Evidence-Based Medicine. Published 2012. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3124652/

- ↑ E Hariton, JJ Locascio. Randomised controlled trials—the gold standard for effectiveness research. Published 2018. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.15199

- ↑ HJA Foulds, SSD Bredin, SA Charlesworth, AC Ivey, DER Warburton. Exercise volume and intensity: a dose–response relationship with health benefits. Published 2014. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00421-014-2887-9

- ↑ a b SJ Day, DG Altman. Blinding in clinical trials and other studies. Published 2000. Available from: https://www.bmj.com/content/321/7259/504

- ↑ AA Delextrat, S Warner, S Graham, E Neupert. An 8-Week Exercise Intervention Based on Zumba Improves Aerobic Fitness and Psychological Well-Being in Healthy Women. Published 2016. Available from: https://journals.humankinetics.com/view/journals/jpah/13/2/article-p131.xml

- ↑ C Fennell, K Peroutky, EL Glickman. Effects of Supervised Training Compared to Unsupervised Training on Physical Activity, Muscular Endurance, and Cardiovascular Parameters. Published 2016. Available from: http://medcraveonline.com/MOJOR/MOJOR-05-00184.pdf

- ↑ PM Spieth, AS Kubasch, AI Penzlin, BM Illigens, K Barlinn, T Siepmann. Randomized controlled trials – a matter of design. Published 2016. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4910682/

- ↑ O Kargiotis, A Paschali, L Messinis, P Papathanasopoulos. Quality of life in multiple sclerosis: Effects of current treatment options. Published 2010. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.3109/09540261003589521

- ↑ JRH Wakefield, S Bickley, F Sani. The effects of identification with a support group on the mental health of people with multiple sclerosis. Published 2013. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2013.02.002

- ↑ JD Crawford, GP McIvor. Group psychotherapy: Benefits in multiple sclerosis. Published 1985. Available from: https://www.archives-pmr.org/article/0003-9993(85)90233-3/abstract

- ↑ E Tarakci, I Yeldan, BE Huseyinsinoglu, Y Zenginler, M Eraksoy. Group exercise training for balance, functional status, spasticity, fatigue and quality of life in multiple sclerosis: a randomized controlled trial. Published 2013. Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/0269215513481047

- ↑ RW Motl, JL Gosney. Effect of exercise training on quality of life in multiple sclerosis: a meta-analysis. Published 2008. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458507080464

- ↑ ME Platta, I Ensari, RW Motl, LA Pilutti. Effect of Exercise Training on Fitness in Multiple Sclerosis: A Meta-Analysis. Published 2016. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2016.01.023

- ↑ EM Snook, RW Motl. Effect of Exercise Training on Walking Mobility in Multiple Sclerosis: A Meta-Analysis. Published 2008. Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1545968308320641

- ↑ RW Motl, E McAuley, EM Snook. Physical activity and quality of life in multiple sclerosis: Possible roles of social support, self-efficacy, and functional limitations. Published 2007. Available from: http://dx.doi.org.ezproxy.canberra.edu.au/10.1037/0090-5550.52.2.143

- ↑ LA Pilutti, ME Platta, RW Motl, AE Latimer-Cheung. The safety of exercise training in multiple sclerosis: A systematic review. Published 2014. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jns.2014.05.016