European History/Challenges to Spiritual Authority

During this period of European history, the Catholic Church, which had become rich and powerful, came under scrutiny. For over a thousand years the Christian religion had bound European states together despite differences in language and customs. Its all-pervading power affected everyone from king to commoner. One of the main Christian tenets is that wealth should be used to alleviate suffering and poverty and that the monetary funds of the church are there specifically for that reason. The central authority of the church had been in Rome for over a thousand years and this concentration of power and money led many to question whether this tenet was being met. In many respects, the northern European countries felt as though the Papal power was now a Papal business. However it must be noted that the Catholic church has always been the dominant institution in southern European countries and in that respect the Reformation can be described as the rise of a uniquely northern European form of Christianity. Whether its aim was to return the church to Christ's message or simply a politically motivated and regional response to the concentration of Papal wealth and power is still a question that divides people.

Causes of the Protestant Reformation

[edit | edit source]Accusations Of Corruption

[edit | edit source]The purchase of church offices (benefices) and the holding of multiple offices (pluralism) had become common during this period. As was the selling of indulgences, or forgiveness from God. To some Christians this was proof that the church had become corrupt. Popes and bishops were accused of being preoccupied with acquiring wealth rather than tending to ecclesiastical matters. The legal exemptions from taxes and criminal charges that they enjoyed led many to believe that they could exploit their position for their own benefit. Clergy were accused of ignoring the church's message on priestly celibacy and poverty therefore weakening the church's moral authority. These accusations eventually turned into a "protest" against Papal power and clerical abuses.

Reactions to Church Corruption

[edit | edit source]These allegations of abuse of authority led some to call for a change. Some clergy and monarchs resented the tithes (a proportion of the sum collected by the church) that they paid to the central Catholic Church in Italy. The Catholic Church had become a major landowner all over Europe and this ownership of extensive areas of land by religious orders, churches, monasteries and cathedrals had not gone unnoticed. With land comes political power, and for any king or lord whose own clergy deferred to a foreign authority the issue was now political rather than religious. The issue also arose about the use of the Latin Bible. It was standard practice for masses to be conducted in Latin though by this period Latin had achieved the archaic nature of a dead language. Though Latin was still the language of scholarly publications, its use in the mass was questioned on evangelist grounds. Christ's message would be better served using the language of the congregation. The invention of the printing press, the decline in Latin and the need to allow the congregation to hear mass in the vernacular led to a break with Christian tradition. John Wycliff initiated the first English translation of the Bible and this is cited by many as the precursor to the Protestant Reformation.

Key Persons of the Reformation

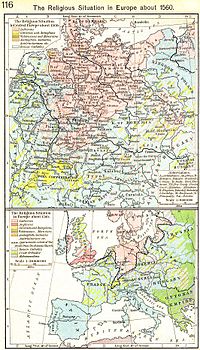

[edit | edit source]From 1521 to 1555, Protestantism spread across Europe. The Reformation started as a religious movement, but became political, and as a result had economic and social impacts.

Martin Luther (1486-1546)

[edit | edit source]Although there were some minor individual outbreaks such as that of John Wycliffe, a young German monk, called Martin Luther was the first to force the issue of the immorality of Church corruption. Disillusioned with the Church, Luther questioned the idea of good works for salvation, including prayers, fasting, and particularly indulgences.

95 Theses

[edit | edit source]In 1517, Luther posted his 95 Theses, though it is debated whether these were nailed to Wittenburg's All Saint's Church, known as Schlosskirche, meaning Castle Church, or his church door. These theses attacked the ideas of salvation through works, the sale of indulgences, and the collection of wealth by the papacy. He formally requested a public debate to settle the issue.

Excommunication

[edit | edit source]Pope Leo X demanded that Luther stop preaching, which Luther refused. He was excommunicated because he did not recant his statements and allegations about indulgences and immoral salvation. He said only scripture can show what the pope has done is ok. He was excommunicated in 1520 and burned the announcement in front of a cheering crowd.

Diet of Worms

[edit | edit source]Luther was demanded by the Holy Roman Emperor Charles to appear before the Diet of Worms in 1521; Luther did not back down from his stance, and was declared a heretic. The Edicts of Worms declared Luther an outlaw and heretic, giving anyone permission to kill Luther without recourse. Due to Luther's popularity in Germany, this could not be enforced.

Lutheranism

[edit | edit source]Lutheranism stresses education for all, including females. According to Lutheran doctrine, marriage is important, and gender roles should be enforced: women belong in the home and should control the economy, while men should control the household. Clergy can marry.

Salvation is attained by faith alone, instead of through works. Religious authority is found in the Bible instead of from the Pope; each man can be his own priest. Religious services are held in vernacular instead of Latin. Only two sacraments are followed: Baptism, and the Lord's Supper. Lutheranism teaches neither "transubstantiation" (the Roman Catholic view that the wine and bread change into the body and blood of Christ) nor "consubstantiation" (the view that the body and blood mingle with the bread and wine to become a third substance), but instead teaches that the Lord's Supper is the true body and blood of Jesus Christ, "in, with and under the bread and wine," given to believers to eat and drink. The benefits of receiving the sacrament come not from the physical eating and drinking, but from Jesus' spoken promise and assurance. In this sense, the sacrament is a proclamation of the Gospel. It is God's Word that makes the Lord's Supper a sacrament, and Luther taught that this means of grace is to be received in faith.

Justification by Faith

[edit | edit source]Chief among Luther's doctrines is Justification by Faith. In it, he attacks the Church's view that good works can get a Christian into heaven. For Luther, because humans are inherently flawed, they can only rely on God's grace to get to heaven, not their own works. Therefore only faith in the grace of God was necessary (and sufficient) to obtain entry to heaven.

The Bible as Supreme Authority

[edit | edit source]Luther said, "... when the Word accompanies the water, Baptism is valid, even though faith be lacking."

Luther challenged the role of the Pope as the supreme temporal authority for interpreting God's will. For Luther, the Bible was the supreme authority of God. As an extension of this philosophy, Luther believed that all Christians should be able to interpret the Scripture (in effect, acting as their own priest). This led Luther to place a heavy emphasis on universal literacy among Christians so that they could read the Bible and attain salvation (a doctrinal point which, along with the advent of the printing press barely more than half a century earlier, led to profound implications for Western society). It also led to Luther's translation of the Bible into German, which he did while in hiding from the wrath of the Holy Roman Emperor. This edition of the Bible became massively popular and made Luther's dialect of German the standard to this day. It also had the intended effect of moving Protestant liturgy into the vernacular.

The Sacraments

[edit | edit source]The Catholic Church at the time of Luther had seven sacraments (with little change today):

- Baptism—The dousing of infants with water to induct them into the church.

- The Eucharist (Holy Communion) -- Taking bread and wine in remembrance of the Last Supper.

- Matrimony—Marriage.

- Holy Orders—Becoming a priest.

- Penance—Making contrition for your sins.

- Confirmation—a kind of coming-of-age rite in which young people are indoctrinated to the church's teachings.

- Last Rites of Extreme Unction (Last Rites) -- At that time an anointing with oil to heal the sick, now more commonly a death rite.

Luther considered all but two of those to be unnecessary, and out of the two he accepted (Baptism and Holy Communion) he considered only baptism to be doctrinally sound. The present Roman Catholic view of the Holy Communion (transubstantiation) developed in the scholastic period. According to this understanding of the Eucharist, Roman Catholic priests were primarily responsible for the bread and wine of the Eucharist becoming the body and blood of Christ. Luther did not believe that the bread and wine changed into the flesh and blood of Christ, but rather that the flesh and blood of Christ was invisibly present "in, with, and under" the bread and wine in the ritual. This "Real Presence" is caused by God and not by a priest thus undercutting the Catholic authority over the sacrament.

Ulrich Zwingli (1484-1531), Zwinglianism

[edit | edit source]Zwinglianism originated in Switzerland, introduced by Ulrich Zwingli. Zwinglism believed in the two sacraments of baptism and communion. The religion advocated most of the key Protestant beliefs. It believed that the Church is the ultimate authority, and it rejected rituals such as fasting and the elaborate ceremonies of Catholicism. Finally, it advocated reform through education.

John Calvin (1504-1564), Calvinism

[edit | edit source]John Calvin founded Calvinism in Geneva, Switzerland; Calvinism later spread to Germany. Calvin was the leading reformer of the second generation of the Reformation, succeeding Martin Luther at the forefront of theological debate and discussion. His most important work was Institutes of the Christian Religion, published in 1541 at the age of 26. At the time, it had a tremendous impact, and many considered Calvin to be a Protestant equivalent of Thomas Aquinas. In it, Calvin outlined the central premises of the religious doctrine which was to bear his name.

Predestination

[edit | edit source]Foremost among these is Calvin's assertion of Double Predestination (often simply referred to as predestination). Single predestination was the doctrine held by most orthodox theologians, including Luther. It said, in essence, that the elect were predestined for heaven. However, they pointed out that those who went to hell went there on their own free will. Calvin objected to this, saying that because all mankind was born in sin, and God had chosen a specific few to go to Heaven through His grace, he must have also chosen an elect who are doomed to damnation. This assertion is based on the commonly accepted view of God as: Omnipotent, Omniscient, Omnipresent, and All-Loving. From these premises, Calvin concluded that not only is there an elect destined for Heaven, but also an elect destined for Hell, and that no one could know with certainty their destination.

The Sacraments

[edit | edit source]Like Martin Luther, Calvin believed that there were only two sacraments in the church: the Eucharist (Holy Communion) and Baptism. With regard to the Eucharist (Holy Communion), Calvin tried to eke out a middle path between the positions which had led to the schism of the Marburg Colloquy. While Luther insisted that the body and blood of Christ were made materially present in the bread and wine of the communion, and Zwingli insisted that the communion was merely a symbol of communion, Calvin said that participating in The Eucharist raised the heart and mind of the believer to feast with Christ in heaven. Calvin's view never took root within the Reformation and it was eventually overshadowed by Luther's and Zwingli's views.

Huguenots

[edit | edit source]French Calvinists that were persecuted because of their religion. The Edict of Nantes gave them the freedom of worship, however during the reign of Louis XIV, the Edict of Fountainbleu was passed. The Edict of Fountainbleu revoked the rights given to the Huguenots.

Chart of Key Religions

[edit | edit source]The below chart offers a simple summary of key details of the major Protestant religions that came to formation, as well as Catholicism.

Religion

|

Key Beliefs/Documents

|

Sacraments

|

Key People and Locations

|

Church/State Relationship

|

| Lutheranism |

|

Two:

|

|

The state is more important than the church |

| Calvinism (aka Presbyterians, Puritans, Huguenots) |

|

Two:

|

|

The church is more important than the state |

| Catholicism |

|

Seven:

|

Throughout Europe, especially in France, Bavaria, the Iberian countries, Austria, Poland and Italy | The church is more important than the state |

The Counter-Reformation

[edit | edit source]The Catholics began their reform movement, which gained momentum in Italy during the 1530s and 1540s. The Catholic Church worked to reform, reaffirm their key beliefs, and then defend their ideology. It is important to recognize that they changed nothing about their core beliefs.

Council of Trent (1545-1563)

[edit | edit source]Pope Paul III and Charles V Hapsburg of Austria convened a general church council at Trent that met sporadically between 1545 and 1563. The Council reasserted the supremacy of clerics over the laity. It did, however, establish seminaries in each diocese to train priests. They reformed indulgences, though the process was continued. They did, however, eliminate pluralism, nepotism, simony, and other similar problems from the church. They reaffirmed their belief of transubstantiation that during the Eucharist, the bread and wine become Christ's body. The Council showed that the schism between Protestants and Catholics had become so severe that all hopes of reconciliation were gone.

Catholic Attempts to Re-convert Protestants and Extend the Faith

[edit | edit source]The Catholic Church used Baroque art to show dramatic biblical scenes and large canvasses. This art was primarily spectator-oriented and was used to make religion more enjoyable to the lay person. In Spain and Rome, Inquisitions, or institutions within the Roman Catholic Church charged with the eradication of heresy, were used to root out heretics. In addition, the Church established the Index of Prohibited Books, which banned books they considered heretical. Finally, the Church sent missionaries around the globe to spread its beliefs and faith.

Jesuits

[edit | edit source]The Society of Jesus, or Jesuits as it was known (founded on August 15, 1534 in France), was a new religious order that arose as a result of the Counter-Reformation. It was founded by former Spanish soldier and priest, St. Ignatius of Loyola (1491–1556), to convert Protestants and non-Christians to Catholicism and add lands to Christendom. The Jesuits vigorously defended the papal authority and the authority of the Catholic Church, thus their title as the "footmen of the Pope".

Missionaries

[edit | edit source]Missionaries visited other distant nations to spread the ideals of Catholicism.

Major Figures

[edit | edit source]The three most Catholic nations in Europe at the time were the Holy Roman Empire, Spain, and France. Important leaders of the Counter-Reformation included:

- Paul III, the pope that called together the Council of Trent

- Charles V Hapsburg, leader of Austria and the most vigorous defender of the Catholic Church at the time in Europe

- Philip II Hapsburg, leader of Spain and Catholic son of Charles V; he married Mary Tudor of England

- "Bloody" Mary Tudor, Catholic daughter of Henry VIII Tudor, she married Philip II

- Catherine de Medici of Florence, regent of France

- Ferdinand II

Prominent Protestant opponents of the Counter-Reformation included:

- Elizabeth Tudor, the leader of England and half-sister of Mary Tudor

- William of Orange, the leader of the Netherlands

- Protestant Princes in the Holy Roman Empire and France

- Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden

The Spanish Reconquista of 1492

[edit | edit source]As a response to the reformation and in an attempt to preserve Catholicism in Spain, Ferdinand and Isabella forcibly expelled Jews and Muslims. Jews who either voluntarily or forced became Christians became known as conversos. Some of them were crypto-Jews who kept practicing Judaism. Eventually all Jews were forced to leave Spain in 1492 by Ferdinand and Isabella. Their converso descendants became victims of the Spanish Inquisition.

Religious Qualms in England

[edit | edit source]In 1547, 10 year old Edward VI, son of Henry VIII and Jane Seymour, took the throne. He was cold, serious, and cruel, and although he was incredibly intelligent and exceptionally capable for his age, he was represented by a regent who controlled the nation. From 1547 until 1549, the regent was Edward Seymour. From 1549 to 1553, the regent was John Dudley. Before Edward's death in 1553, he signed a will leaving the throne to Lady Jane Grey out of fear that his sister Mary would convert England back to Catholicism.

Lady Jane Grey ruled for nine days, but she and Dudley were soon arrested because Mary Tudor began to gain support since she was the rightful heir to the throne upon Edward's death.

"Bloody" Mary Tudor thus took the throne in 1553 and ruled until 1558. She was proud, stubborn, vain, vulnerable to flattery, but most of all, she was highly Catholic. In 1554, she converted England back to Catholicism and burnt hundreds of Protestants at the stake, thus earning her nickname "Bloody" Mary. She married Philip II of Spain. However, as a result of her illness from ovarian cancer, she was forced to recognize her Protestant sister Elizabeth as the heir.

European History

01. Background •

02. Middle Ages •

03. Renaissance •

04. Exploration •

05. Reformation

06. Religious War •

07. Absolutism •

08. Enlightenment •

09. French Revolution •

10. Napoleon

11. Age of Revolutions •

12. Imperialism •

13. World War I •

14. 1918 to 1945 •

15. 1945 to Present

Glossary •

Outline •

Authors •

Bibliography