Adventist Youth Honors Answer Book/Recreation/Abseiling

| Abseiling | ||

|---|---|---|

| Recreation South Pacific Division See also Abseiling - Advanced |

Skill Level Unknown |

|

| Year of Introduction: Unknown | ||

Safety

[edit | edit source]1. a. List and explain the safety rules

[edit | edit source]1. b. Explain the “dangers of falling” chart.

[edit | edit source]2. Explain the uses of the following knots:

[edit | edit source]a. Tape

[edit | edit source]b. Alpine butterfly

[edit | edit source]c. Figure of eight loop

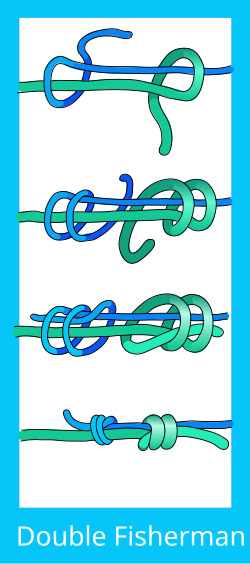

[edit | edit source]d. Double fishermans

[edit | edit source]e. Prussik

[edit | edit source]f. Bowline

[edit | edit source]

Setup

[edit | edit source]3. Draw the diagrams for the setting up of the following abseil descents:

[edit | edit source]a. Single rope technique

[edit | edit source]b. Canyoning setup

[edit | edit source]4. Know the ways to identify safe anchors in various circumstances, e.g. trees, boulders, bollards. Belaying

[edit | edit source]5. Explain the various verbal calls.

[edit | edit source]6. Explain the principle of belaying and the three methods used, and give the advantages and disadvantages of each method:

[edit | edit source]a. Body belay

[edit | edit source]b. Mechanical belay

[edit | edit source]c. Base belay

[edit | edit source]Care of Equipment

[edit | edit source]7. List the rules for care of ropes.

[edit | edit source]How To Coil a Climbing Rope

If you are storing your rope for a while or stuffing it away in a back pack, coiling a climbing rope is worth the effort and will save you lots of time untangling knots that have mysteriously tied themselves in the middle of it.

Coiling a Climbing Rope

Step 1

Hold the middle of your rope in one hand and loop both strands over your shoulders. Some ropes have a convenient middle marker to make this easy. If yours doesn't, find both ends and hold them together. Then shuffle both the strands of rope through your hands until you get to the middle point.

Step 2

Reach across and grab the rope below your other hand.

Step 3

Pull your hand along the rope, creating enough space to flick the next two strands over your head, so they rest on your shoulders with the first two. Repeat this with your other hand in the opposite direction.

Step 4

Keep draping the rope over your shoulders until there is about four meters left. Use both hands to take the rope off your shoulders, and drape the middle of the loops over your arm.

Step 5

Wrap the two ends of the rope tightly around all the coils near the top. Do this three or four times. It's best to go from the bottom upwards.

Step 6

Push a loop of each end through the top of the main coils as shown.

Step 7

Pass the two ends of the rope through these loops. Pull it all tight and your rope is coiled!

Step 8

If the tails of rope are long enough (at least 1 meter), you can tie the rope on your back. Pull the tails over your shoulders, cross them over your chest, then wrap them in opposite directions around your back. Bring the ends in front of you and tie them together around your waist.

How To Stack a Climbing Rope

Coiling a climbing rope is useful when you need to carry it or pack it away neatly, but you'll need to 'stack' the rope so that it will feed out without tangles while you're climbing. Beginning at one end, simply feed the rope into a pile on top of your rope bag, or a clean area of the ground. Tying the ends of the rope into the straps of your rope bag makes it easier to find them. When preparing to lead climb, the leader will tie into the top end of the rope.

8. Explain the difference between dynamic and static rope.

[edit | edit source]Dynamic rope is usually used for climbing activities where stretch to absorb the shock from a leader fall while on belay or climbing while roped with a team is expected. The dynamic function decreases deceleration injury and preserves the rope. After hard falls ropes may need to be retired from leader use.

Static ropes are built with little or no stretch. They are best suited for caving, Abseiling and static safety tied ropes.

9. Know the right type of equipment needed for abseiling.

[edit | edit source]Personal Protective Equipment (PPE)

A helmet will protect your head from falling rocks or other impacts. Here is what you should look for. Light weight Well ventilated Fits comfortably on your head and you can forget you’re even wearing soon after you put it on. Always wear a helmet.

A harness. A wide padded waist belt harness with loops for carrying gear is good. Tape harnesses are ample but not very comfortable. The harness must be fitted correctly...it should be fitted firmly above the hips around the waist first, then leg loops should be adjusted firmly. There should be no pressure spots, wedging or chaffing from quality harness.

Gloves. Novices such as school groups who do abseiling only while on an instructors safety belay will usually use gloves. Their hands are soft and easily blistered and as a beginner they tend to get rope burn by letting the rope loose then grasping it in fear or excitement. Choose gloves that fit your hand size, and not the one size fits all type garden variety. The perfect glove is a mitten type with padded palms and exposed fingers.

Footwear. Climbing shoes are not necessary but sturdy footwear is recommended.

Ropes...

Belay devices...

10. Know the best way to store your ropes, e.g. coiling and chaining.

[edit | edit source]Be aware that moisture, extreme temperatures Ultraviolet light, chemicals, abrasion and dirt can all damage ropes. Keeping them clean, dry and protected is mission critical to a full lifespan of the rope.

Descenders

[edit | edit source]11 a. Know which descending device to use in different abseils.

[edit | edit source]11 b. Give reasons why you chose that device, e.g. on/off time, security, heat, versatility, etc.

[edit | edit source]First Aid

[edit | edit source]12. Know about how to treat a patient for the following injuries:

[edit | edit source]a. Sprains

[edit | edit source]Adventist Youth Honors Answer Book/First aid/Sprains

b. Concussion

[edit | edit source]Adventist Youth Honors Answer Book/First aid/Concussion

c. Hypothermia

[edit | edit source]Hypothermia is caused by continued exposure to low or rapidly falling temperatures, cold moisture, snow, or ice. Those exposed to low temperatures for extended periods may suffer ill effects, even if they are well protected by clothing, because cold affects the body systems slowly, almost without notice. As the body cools, there are several stages of progressive discomfort and disability. The first symptom is shivering, which is an attempt to generate heat by repeated contractions of surface muscles. This is followed by a feeling of listlessness, indifference, and drowsiness. Unconsciousness can follow quickly. Shock becomes evident as the victim’s eyes assume a glassy stare, respiration becomes slow and shallow, and the pulse is weak or absent. As the body temperature drops even lower, peripheral circulation decreases and the extremities become susceptible to freezing. Finally, death results as the core temperature of the body approaches 80 °F (27 °C). The steps for treatment of hypothermia are as follows:

- Carefully observe respiratory effort and heart beat; CPR may be required while the warming process is underway.

- Rewarm the victim as soon as possible. It may be necessary to treat other injuries before the victim can be moved to a warmer place. Severe bleeding must be controlled and fractures splinted over clothing before the victim is moved.

- Replace wet or frozen clothing and remove anything that constricts the victim’s arms, legs, or fingers, interfering with circulation.

- If the victim is inside a warm place and is conscious, the most effective method of warming is immersion in a tub of warm (100° to 105 °F or 38° to 41 °C) water. The water should be warm to the elbow - never hot. Observe closely for signs of respiratory failure and cardiac arrest (rewarming shock). Rewarming shock can be minimized by warming the body trunk before the limbs to prevent vasodilation in the extremities with subsequent shock due to blood volume shifts.

- If a tub is not available, apply external heat to both sides of the victim. Natural body heat (skin to skin) from two rescuers is the best method. This is called “buddy warming.” If this is not practical, use hot water bottles or an electric rewarming blanket. Do not place the blanket or bottles next to bare skin, however, and be careful to monitor the temperature of the artificial heat source, since the victim is very susceptible to burn injury. Because the victim is unable to generate adequate body heat, placement under a blanket or in a sleeping bag is not sufficient treatment.

- If the victim is conscious, give warm liquids to drink. Never give alcoholic beverages or allow the victim to smoke.

- Dry the victim thoroughly if water is used for rewarming.

- As soon as possible, transfer the victim to a definitive care facility. Be alert for the signs of respiratory and cardiac arrest during transfer, and keep the victim warm.

d. Broken bone

[edit | edit source]Splints An essential part of the first-aid treatment is immobilizing the injured part with splints so that the sharp ends of broken bones won’t move around and cause further damage to nerves, blood vessels, or vital organs. Splints are also used to immobilize severely injured joints or muscles and to prevent the enlargement of extensive wounds.

Before you can use a splint, you need to have a general understanding of the use of splints. In an emergency, almost any firm object or material can be used as a splint. Such things as umbrellas, canes, tent pegs, sticks, oars, paddles, spars, wire, leather, boards, pillows, heavy clothing, corrugated cardboard, and folded newspapers can be used as splints. A fractured leg may sometimes be splinted by fastening it securely to the uninjured leg. Splints, whether ready-made or improvised, must meet the following requirements:

- Be light in weight, but still be strong and fairly rigid.

- Be long enough to reach the joints above and below the fracture.

- Be wide enough so the bandages used to hold them in place won’t pinch the injured part.

- Be well padded on the sides that touch the body. If they’re not properly padded, they won’t fit well and won’t adequately immobilize the injured part.

- To improvise the padding for a splint, use articles of clothing, bandages, cotton, blankets, or any other soft material.

- If the victim is wearing heavy clothes, apply the splint on the outside, allowing the clothing to serve as at least part of the required padding.

Although splints should be applied snugly, never apply them tight enough to interfere with the circulation of the blood. When applying splints to an arm or a leg, try to leave the fingers or toes exposed. If the tips of the fingers or toes become blue or cold, you will know that the splints or bandages are too tight. You should examine a splinted part approximately every half-hour, and loosen the fastenings if circulation appears to be cut off. Remember that any injured part is likely to swell, and splints or bandages that are all right when applied may be too tight later.

To secure the limb to the splint, belts, neckerchiefs, rope, or any suitable material may be used. If possible, tie the limb at two places above and two places below the break. Leave the treatment of other types of fractures, such as jaw, ribs, and spine, to medical personnel. Never try to move a person who might have a fractured spine or neck. Moving such a person could cause permanent paralysis. Don’t attempt to reset bones.

Forearm

There are two long bones in the forearm, the radius and the ulna. When both are broken, the arm usually appears to be deformed. When only one is broken, the other acts as a splint and the arm retains a more or less natural appearance. Any fracture of the forearm is likely to result in pain, tenderness, inability to use the forearm, and a kind of wobbly motion at the point of injury. If the fracture is open, a bone will show through. If the fracture is open, stop the bleeding and treat the wound. Apply a sterile dressing over the wound. Carefully straighten the forearm. (Remember that rough handling of a closed fracture may turn it into an open fracture.) Apply two well-padded splints to the forearm, one on the top and one on the bottom. Be sure that the splints are long enough to extend from the elbow to the wrist. Use bandages to hold the splints in place. Put the forearm across the chest. The palm of the hand should be turned in, with the thumb pointing upward. Support the forearm in this position by means of a wide sling and a cravat bandage (see illustration). The hand should be raised about 4 inches above the level of the elbow. Treat the victim for shock and evacuate as soon as possible.

Upper Arm

The signs of fracture of the upper arm include pain, tenderness, swelling, and a wobbly motion at the point of fracture. If the fracture is near the elbow, the arm is likely to be straight with no bend at the elbow. If the fracture is open, stop the bleeding and treat the wound before attempting to treat the fracture.

- NOTE

- Treatment of the fracture depends partly upon the location of the break.

If the fracture is in the upper part of the arm near the shoulder, place a pad or folded towel in the armpit, bandage the arm securely to the body, and support the forearm in a narrow sling.

If the fracture is in the middle of the upper arm, you can use one well-padded splint on the outside of the arm. The splint should extend from the shoulder to the elbow. Fasten the splinted arm firmly to the body and support the forearm in a narrow sling, as illustrated.

Another way of treating a fracture in the middle of the upper arm is to fasten two wide splints (or four narrow ones) about the arm and then support the forearm in a narrow sling. If you use a splint between the arm and the body, be very careful that it does not extend too far up into the armpit; a splint in this position can cause a dangerous compression of the blood vessels and nerves and may be extremely painful to the victim. If the fracture is at or near the elbow, the arm may be either bent or straight. No matter in what position you find the arm, DO NOT ATTEMPT TO STRAIGHTEN IT OR MOVE IT IN ANY WAY. Splint the arm as carefully as possible in the position in which you find it. This will prevent further nerve and blood vessel damage. The only exception to this is if there is no pulse on the other side of the fracture (relative to the heart), in which case gentle traction is applied and then the arm is splinted. Treat the victim for shock and get him under the care of a medical professional as soon as possible.

Kneecap

Carefully straighten the injured limb. Immobilize the fracture by placing a padded board under the injured limb. The board should be at least 4 inches wide and should reach from the but- tock to the heel. Place extra padding under the knee and just above the heel, as shown in the illustration. Use strips of bandage to fasten the leg to the board in four places: (1) just below the knee; (2) just above the knee; (3) at the ankle; and (4) at the thigh. DO NOT COVER THE KNEE ITSELF. Swelling is likely to occur very rapidly, and any bandage or tie fastened over the knee would quickly become too tight. Treat the victim for shock and evacuate as soon as possible.

Ankle

The figure-eight bandage is used for dressings of the ankle, as well as for supporting a sprain. While keeping the foot at a right angle, start a 3-inch bandage around the instep for several turns to anchor it. Carry the bandage upward over the instep and around behind the ankle, forward, and again across the instep and down under the arch, thus completing one figure-eight. Continue the figure-eight turns, overlapping one-third to one-half the width of the bandage and with an occasional turn around the ankle, until the compress is secured or until adequate support is obtained.

e. Shock

[edit | edit source]Shock is a medical condition where the delivery of oxygen and nutrients is insufficient to meet the body's needs. The main carrier of oxygen and nutrients in the body is the blood, so anytime there is a loss of blood, there is a risk of shock.

First aid treatment of shock includes:

- Immediate reassurance and comforting the victim if conscious.

- If alone, go for help. If not, send someone to go for help and someone stay with the victim.

- Ensure that the airway is clear and check for breathing. Place the victim in the recovery position if possible.

- Attempt to stop any obvious bleeding.

- Cover the victim with a blanket or jacket, but not too thick or it may cause a dangerous drop in blood pressure.

- Do not give a drink. Moisten lips if requested.

- Prepare for cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR).

Cliff Rescue

[edit | edit source]13. Explain how to perform the following rescues:

[edit | edit source]a. The pulley system

[edit | edit source]b. The change-over method

[edit | edit source]SECTION TWO-PRACTICAL

[edit | edit source]1. Pass the abseiling exam with a pass mark of 60%. The exam is available from the conference youth ministries office, or through the instructor.

[edit | edit source]Verbal Testing

[edit | edit source]2. Answer the questions on the following topics:

[edit | edit source]a. Uses of the six abseiling knots

[edit | edit source]b. What are, and give the meaning of the standard climbing calls

[edit | edit source]c. Uses of various descenders

[edit | edit source]d. Give seven rules for are of rope

[edit | edit source]e. Give seven rules for safety

[edit | edit source]f. Know about first aid and how to treat patients

[edit | edit source]g. Give five ways to detect faults of ropes

[edit | edit source]Practical Testing

[edit | edit source]3. Perform the following tasks:

[edit | edit source]a. Tie the six knots

[edit | edit source]b. Set up the single rope setup and canyoning setup

[edit | edit source]c. Witness a cliff rescue demonstrated by the instructor

[edit | edit source]d. Coil and chain a rope

[edit | edit source]e. Set up the belay methods

[edit | edit source]Abseiling

[edit | edit source]4. From a minimum height of 10 meters, complete two abseils on each of the following devices, and know how to attach them to the rope:

[edit | edit source]a. Whale tail

[edit | edit source]b. Robot

[edit | edit source]c. Harpoon (easy access)

[edit | edit source]d. Figure of eight

[edit | edit source]e. Piton-brake bar

[edit | edit source]f. Rappel-rack

[edit | edit source]g. Harpoon (conventional)

[edit | edit source]h. Cross karabiner

[edit | edit source]5. Explain how to do the classic abseil, and over the shoulder abseil, for emergency use.

[edit | edit source]6. Be able to prussik a ten-meter cliff.

[edit | edit source]References

[edit | edit source]- Book:Adventist Youth Honors Answer Book/Honors with an Advanced Option

- Book:Adventist Youth Honors Answer Book/Honors

- Book:Adventist Youth Honors Answer Book

- Book:Adventist Youth Honors Answer Book/Skill Level Unknown

- Book:Adventist Youth Honors Answer Book/Honors Introduced in Unknown

- Book:Adventist Youth Honors Answer Book/Recreation

- Book:Adventist Youth Honors Answer Book/South Pacific Division

- Book:Adventist Youth Honors Answer Book/Overlapping requirements