Fukushima Aftermath: Whither the Indian Point Nuke?/Pressurized water reactor

Pressurized water reactors (PWRs) constitute a majority of all western nuclear power plants and are one of two types of light water reactor (LWR), the other type being boiling water reactors (BWRs). In a PWR the primary coolant (water) is pumped under high pressure to the reactor core where it is heated by the energy generated by the fission of atoms. The heated water then flows to a steam generator where it transfers its thermal energy to a secondary system where steam is generated and flows to turbines which, in turn, spins an electric generator. In contrast to a boiling water reactor, pressure in the primary coolant loop prevents the water from boiling within the reactor. All LWRs use ordinary water as both coolant and neutron moderator.

PWRs were originally designed to serve as nuclear propulsion for nuclear submarines and were used in the original design of the second commercial power plant at Shippingport Atomic Power Station.

PWRs currently operating in the United States are considered Generation II reactors. Russia's VVER reactors are similar to U.S. PWRs. France operates many PWRs to generate the bulk of their electricity.

History

[edit | edit source]

Several hundred PWRs are used for marine propulsion in aircraft carriers, nuclear submarines and ice breakers. In the US, they were originally designed at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory for use as a nuclear submarine power plant. Follow-on work was conducted by Westinghouse Bettis Atomic Power Laboratory.[1] The first commercial nuclear power plant at Shippingport Atomic Power Station was originally designed as a pressurized water reactor, on insistence from Admiral Hyman G. Rickover that a viable commercial plant would include none of the "crazy thermodynamic cycles that everyone else wants to build."[2]

The US Army Nuclear Power Program operated pressurized water reactors from 1954 to 1974.

Three Mile Island Nuclear Generating Station initially operated two pressurized water reactor plants, TMI-1 and TMI-2.[3] The partial meltdown of TMI-2 in 1979 essentially ended the growth in new construction nuclear power plants in the United States.[4]

Design

[edit | edit source]

Nuclear fuel in the reactor vessel is engaged in a fission chain reaction, which produces heat, heating the water in the primary coolant loop by thermal conduction through the fuel cladding. The hot primary coolant is pumped into a heat exchanger called the steam generator, where it flows through hundreds or thousands of tubes (usually 3/4 inch in diameter). Heat is transferred through the walls of these tubes to the lower pressure secondary coolant located on the sheet side of the exchanger where it evaporates to pressurized steam. The transfer of heat is accomplished without mixing the two fluids, which is desirable since the primary coolant might become radioactive. Some common steam generator arrangements are u-tubes or single pass heat exchangers.

In a nuclear power station, the pressurized steam is fed through a steam turbine which drives an electrical generator connected to the electric grid for distribution. After passing through the turbine the secondary coolant (water-steam mixture) is cooled down and condensed in a condenser. The condenser converts the steam to a liquid so that it can be pumped back into the steam generator, and maintains a vacuum at the turbine outlet so that the pressure drop across the turbine, and hence the energy extracted from the steam, is maximized. Before being fed into the steam generator, the condensed steam (referred to as feedwater) is sometimes preheated in order to minimize thermal shock.[5]

The steam generated has other uses besides power generation. In nuclear ships and submarines, the steam is fed through a steam turbine connected to a set of speed reduction gears to a shaft used for propulsion. Direct mechanical action by expansion of the steam can be used for a steam-powered aircraft catapult or similar applications. District heating by the steam is used in some countries and direct heating is applied to internal plant applications.

Two things are characteristic for the pressurized water reactor (PWR) when compared with other reactor types: coolant loop separation from the steam system and pressure inside the primary coolant loop. In a PWR, there are two separate coolant loops (primary and secondary), which are both filled with demineralized/deionized water. A boiling water reactor, by contrast, has only one coolant loop, while more exotic designs such as breeder reactors use substances other than water for coolant and moderator (e.g. sodium in its liquid state as coolant or graphite as a moderator). The pressure in the primary coolant loop is typically 15–16 megapascals (150–160 bar), which is notably higher than in other nuclear reactors, and nearly twice that of a boiling water reactor (BWR). As an effect of this, only localized boiling occurs and steam will recondense promptly in the bulk fluid. By contrast, in a boiling water reactor the primary coolant is designed to boil.[6]

PWR reactor design

[edit | edit source]

Coolant

[edit | edit source]Light water is used as the primary coolant in a PWR. It enters the bottom of the reactor core at about 275 °C (530 °F) and is heated as it flows upwards through the reactor core to a temperature of about 315 °C (600 °F). The water remains liquid despite the high temperature due to the high pressure in the primary coolant loop, usually around 155 bar (15.5 MPa 153 atm, 2,250 psig). In water, the critical point occurs at around 647 K (374 °C or 705 °F) and 22.064 MPa (3200 PSIA or 218 atm.[7]

Pressure in the primary circuit is maintained by a pressurizer, a separate vessel that is connected to the primary circuit and partially filled with water which is heated to the saturation temperature (boiling point) for the desired pressure by submerged electrical heaters. To achieve a pressure of 155 bar, the pressurizer temperature is maintained at 345 °C, which gives a subcooling margin (the difference between the pressurizer temperature and the highest temperature in the reactor core) of 30 °C. Thermal transients in the reactor coolant system result in large swings in pressurizer liquid volume, total pressurizer volume is designed around absorbing these transients without uncovering the heaters or emptying the pressurizer. Pressure transients in the primary coolant system manifest as temperature transients in the pressurizer and are controlled through the use of automatic heaters and water spray, which raise and lower pressurizer temperature, respectively.[8]

To achieve maximum heat transfer, the primary circuit temperature, pressure and flow rate are arranged such that subcooled nucleate boiling takes place as the coolant passes over the nuclear fuel rods.

The coolant is pumped around the primary circuit by powerful pumps, which can consume up to 6 MW each.[9] After picking up heat as it passes through the reactor core, the primary coolant transfers heat in a steam generator to water in a lower pressure secondary circuit, evaporating the secondary coolant to saturated steam — in most designs 6.2 MPa (60 atm, 900 psia), 275 °C (530 °F) — for use in the steam turbine. The cooled primary coolant is then returned to the reactor vessel to be heated again.

Moderator

[edit | edit source]Pressurized water reactors, like all thermal reactor designs, require the fast fission neutrons to be slowed down (a process called moderation or thermalization) in order to interact with the nuclear fuel and sustain the chain reaction. In PWRs the coolant water is used as a moderator by letting the neutrons undergo multiple collisions with light hydrogen atoms in the water, losing speed in the process. This "moderating" of neutrons will happen more often when the water is denser (more collisions will occur). The use of water as a moderator is an important safety feature of PWRs, as an increase in temperature may cause the water to turn to steam - thereby reducing the extent to which neutrons are slowed down and hence reducing the reactivity in the reactor. Therefore, if reactivity increases beyond normal, the reduced moderation of neutrons will cause the chain reaction to slow down, producing less heat. This property, known as the negative temperature coefficient of reactivity, makes PWR reactors very stable.

In contrast, the RBMK reactor design used at Chernobyl, which uses graphite instead of water as the moderator and uses boiling water as the coolant, has a large positive thermal coefficient of reactivity, that increases heat generation when coolant water temperatures increase. This makes the RBMK design less stable than pressurized water reactors. In addition to its property of slowing down neutrons when serving as a moderator, water also has a property of absorbing neutrons, albeit to a lesser degree. When the coolant water temperature increases, the boiling increases, which creates voids. Thus there is less water to absorb thermal neutrons that have already been slowed down by the graphite moderator, causing an increase in reactivity. This property is called the void coefficient of reactivity, and in an RBMK reactor like Chernobyl, the void coefficient is positive, and fairly large, causing rapid transients. This design characteristic of the RBMK reactor is generally seen as one of several causes of the Chernobyl accident.[10]

Heavy water has very low neutron absorption, so heavy water reactors such as CANDU reactors also have a positive void coefficient, though it is not as large as that of an RBMK like Chernobyl; these reactors are designed with a number of safety systems not found in the original RBMK design, which are designed to handle or react to this as needed.

PWRs are designed to be maintained in an undermoderated state, meaning that there is room for increased water volume or density to further increase moderation, because if moderation were near saturation, then a reduction in density of the moderator/coolant could reduce neutron absorption significantly while reducing moderation only slightly, making the void coefficient positive. Also, light water is actually a somewhat stronger moderator of neutrons than heavy water, though heavy water's neutron absorption is much lower. Because of these two facts, light water reactors have a relatively small moderator volume and therefore have compact cores. One next generation design, the supercritical water reactor, is even less moderated. A less moderated neutron energy spectrum does worsen the capture/fission ratio for 235U and especially 239Pu, meaning that more fissile nuclei fail to fission on neutron absorption and instead capture the neutron to become a heavier nonfissile isotope, wasting one or more neutrons and increasing accumulation of heavy transuranic actinides, some of which have long half-lives.

Fuel

[edit | edit source]

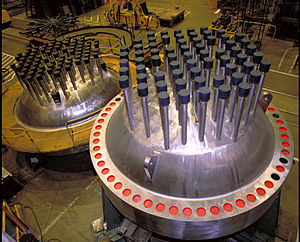

After enrichment the uranium dioxide (UO2) powder is fired in a high-temperature, sintering furnace to create hard, ceramic pellets of enriched uranium dioxide. The cylindrical pellets are then clad in a corrosion-resistant zirconium metal alloy Zircaloy which are backfilled with helium to aid heat conduction and detect leakages. Zircaloy is chosen because of its mechanical properties and its low absorption cross section.[11] The finished fuel rods are grouped in fuel assemblies, called fuel bundles, that are then used to build the core of the reactor. A typical PWR has fuel assemblies of 200 to 300 rods each, and a large reactor would have about 150–250 such assemblies with 80–100 tonnes of uranium in all. Generally, the fuel bundles consist of fuel rods bundled 14 × 14 to 17 × 17. A PWR produces on the order of 900 to 1,500 MWe. PWR fuel bundles are about 4 meters in length.[12]

Refuelings for most commercial PWRs is on an 18–24 month cycle. Approximately one third of the core is replaced each refueling, though some more modern refueling schemes may reduce refuel time to a few days and allow refueling to occur on a shorter periodicity.[13]

Control

[edit | edit source]In PWRs reactor power can be viewed as following steam (turbine) demand due to the reactivity feedback of the temperature change caused by increased or decreased steam flow. Boron and control rods are used to maintain primary system temperature at the desired point. In order to decrease power, the operator throttles shut turbine inlet valves. This would result in less steam being drawn from the steam generators. This results in the primary loop increasing in temperature. The higher temperature causes the reactor to fission less and decrease in power. The operator could then add boric acid and/or insert control rods to decrease temperature to the desired point.

Reactivity adjustment to maintain 100% power as the fuel is burned up in most commercial PWRs is normally achieved by varying the concentration of boric acid dissolved in the primary reactor coolant. Boron readily absorbs neutrons and increasing or decreasing its concentration in the reactor coolant will therefore affect the neutron activity correspondingly. An entire control system involving high pressure pumps (usually called the charging and letdown system) is required to remove water from the high pressure primary loop and re-inject the water back in with differing concentrations of boric acid. The reactor control rods, inserted through the reactor vessel head directly into the fuel bundles, are moved for the following reasons:

- To start up the reactor.

- To shut down the primary nuclear reactions in the reactor.

- To accommodate short term transients such as changes to load on the turbine.

The control rods can also be used:

- To compensate for nuclear poison inventory.

- To compensate for nuclear fuel depletion.

but these effects are more usually accommodated by altering the primary coolant boric acid concentration.

In contrast, BWRs have no boron in the reactor coolant and control the reactor power by adjusting the reactor coolant flow rate

Advantages

[edit | edit source]- PWR reactors are very stable due to their tendency to produce less power as temperatures increase; this makes the reactor easier to operate from a stability standpoint as long as the post shutdown period of 1 to 3 years has pumped cooling.

- PWR turbine cycle loop is separate from the primary loop, so the water in the secondary loop is not contaminated by radioactive materials.

- PWRs can passively scram the reactor in the event that offsite power is lost to immediately stop the primary nuclear reaction. The control rods are held by electromagnets and fall by gravity when current is lost; full insertion safely shuts down the primary nuclear reaction. However, nuclear reactions of the fission products continue to generate decay heat at initially roughly 7% of full power level, which requires 1 to 3 years of water pumped cooling. If cooling fails during this post-shutdown period, the reactor can still overheat and meltdown. Upon loss of coolant the decay heat can raise the rods above 2200 degrees Celsius, where upon the hot Zirconium alloy metal used for casing the nuclear fuel rods spontaneously explodes in contact with the cooling water or steam, which leads to the separation of water in to its constituent elements (hydrogen and oxygen). In this event there is a high danger of hydrogen explosions, threatening structural damage and/or the exposure of highly radioactive stored fuel rods in the vicinity outside the plant in pools (approximately 15 tons of fuel is replenished each year to maintain normal PWR operation).

Disadvantages

[edit | edit source]- The coolant water must be highly pressurized to remain liquid at high temperatures. This requires high strength piping and a heavy pressure vessel and hence increases construction costs. The higher pressure can increase the consequences of a loss-of-coolant accident.[14] The reactor pressure vessel is manufactured from ductile steel but, as the plant is operated, neutron flux from the reactor causes this steel to become less ductile. Eventually the ductility of the steel will reach limits determined by the applicable boiler and pressure vessel standards, and the pressure vessel must be repaired or replaced. This might not be practical or economic, and so determines the life of the plant.

- Additional high pressure components such as reactor coolant pumps, pressurizer, steam generators, etc. are also needed. This also increases the capital cost and complexity of a PWR power plant.

- The high temperature water coolant with boric acid dissolved in it is corrosive to carbon steel (but not stainless steel); this can cause radioactive corrosion products to circulate in the primary coolant loop. This not only limits the lifetime of the reactor, but the systems that filter out the corrosion products and adjust the boric acid concentration add significantly to the overall cost of the reactor and to radiation exposure. Occasionally, this has resulted in severe corrosion to control rod drive mechanisms when the boric acid solution leaked through the seal between the mechanism itself and the primary system.[15][16]

- Natural uranium is only 0.7% uranium-235, the isotope necessary for thermal reactors. This makes it necessary to enrich the uranium fuel, which increases the costs of fuel production. If heavy water is used, it is possible to operate the reactor with natural uranium, but the production of heavy water requires large amounts of energy and is hence expensive.

- Because water acts as a neutron moderator, it is not possible to build a fast neutron reactor with a PWR design. A reduced moderation water reactor may however achieve a breeding ratio greater than unity, though this reactor design has disadvantages of its own.[17]

Notes

[edit | edit source]- ↑ "Rickover: Setting the Nuclear Navy's Course". ORNL Review. Oak Ridge National Laboratory, United States Department of Energy. Retrieved 2008-05-21.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help) - ↑ Rockwell, Theodore (1992). The Rickover Effect. Naval Institute Press. p. 162. ISBN 1557507023.

- ↑ Mosey 1990, pp.69–71

- ↑ "50 Years of Nuclear Energy" (PDF). IAEA. Retrieved 2008-12-29.

- ↑ Glasstone & Senonske 1994, pp. 769

- ↑ Duderstadt & Hamilton 1976, pp. 91–92

- ↑ International Association for the Properties of Water and Steam, 2007.

- ↑ Glasstone & Senonske 1994, pp. 767

- ↑ Tong 1988, pp. 175

- ↑ Mosey 1990, pp. 92–94

- ↑ Forty, C.B.A. "Uses of Zirconium Alloys in Fusion Applications" (PDF). EURATOM/UKAEA Fusion Association, Culham Science Centre. Retrieved 2008-05-21.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ↑ Glasstone & Sesonske 1994, pp. 21

- ↑ Duderstadt & Hamilton 1976, pp. 598

- ↑ Tong 1988, pp. 216–217

- ↑ "Davis-Besse: The Reactor with a Hole in its Head" (PDF). UCS -- Aging Nuclear Plants. Union of Concerned Scientists. http://www.ucsusa.org/assets/documents/nuclear_power/acfnx8tzc.pdf. Retrieved 2008-07-01.

- ↑ Wald, Matthew (May 1, 2003). "Extraordinary Reactor Leak Gets the Industry's Attention". New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2003/05/01/us/extraordinary-reactor-leak-gets-the-industry-s-attention.html. Retrieved 2009-09-10.

- ↑ Duderstadt & Hamilton 1976, pp. 86

References

[edit | edit source]- Duderstadt, James J. (1976). Nuclear Reactor Analysis. Wiley. ISBN 0471223638.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Glasstone, Samuel (1994). Nuclear Reactor Engineering. Chapman and Hall. ISBN 0412985217.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Mosey, David (1990). Reactor Accidents. Nuclear Engineering International Special Publications. pp. 92–94. ISBN 0408061987.

- Tong, L.S. (1988). Principles of Design Improvement for Light Water Reactors. Hemisphere. ISBN 0891164162.

External links

[edit | edit source]- Nuclear Science and Engineering at MIT OpenCourseWare.

- Document archives at the website of the United States Nuclear Regulatory Commission.

- Operating Principles of a Pressurized Water Reactor (YouTube video).