Cognition and Instruction/Learning to Read

Reading is a crucial skill as it helps us learn in all academic subjects and is so important for success outside the classroom. Learning to read is a complex, multi-year process of learning to recognize the sounds and meanings of symbols and written words. Reading ability is an important achievement for children because it is their entry point into the world of literacy and learning upon which much of life depends.

This chapter covers several aspects of learning to read, beginning with the cognitive factors of reading including memory and attention. Different types of reading difficulties and disabilities are reviewed, with some implications for teaching. As each child is different, there is no single method that can be used to teach all children with reading difficulties or disabilities. The chapter discusses the three stages of reading, moving from children who do not know how to read or recognize any words all the way to children who have the ability to connect letters and their sounds in order to decode unfamiliar words. Reading instruction today tends to combine and adapt methods derived from different theories to address the needs of individual learners. Finally, we discuss several ways of effectively assessing reading progress.

Cognitive Factors of Reading[edit | edit source]

Success in reading depends on using the cognitive abilities of working and long-term memory, and also focusing attention in order to make meaning of the text. In addition, the reader must have some knowledge about the world around them in order to comprehend the information.

Memory[edit | edit source]

Working and long-term memory are cognitive factors that have to do with children’s success in learning to read. Reading is an act of memory because it depends on world and linguistic knowledge [1]. When a child is learning a word they have to keep that word in their mind long enough to build up the more complex meaning of phrases, sentences, and whole passages [2]. The temporary storage of material that a child has read depends on working memory [3]. The working memory is different from the other forms of memory due to the fact that it reflects both processing and storage [4]. Working memory is often studied when learning about children’s reading development, and Baddeley's model is often used to describe the relation between working memory and reading development [5]. This model involves two basic aspects: the phonological loop and the visual sketchpad [6]. The processing of phonological information has an inner rehearsal aspect, called the articulatory loop, which allows the phonological information needed for word decoding and reading comprehension to be retained longer in memory [7]. When children are not able to, or have problems decoding words, it is then associated with difficulties in phonological awareness [8]. Children with these difficulties are unable to understand or have access to the sound structure of spoken language [9]. When children are young their working memory capacity is restricted due to the fact that they lack the well-developed skills needed for encoding and rehearsal [10]. In order to make reading meaningful both working and long term memory are needed [11]. Thus, when children learn new information, the information must be kept fresh in their working memory while they retrieve previously learned information from their long-term memory [12]. In order for children to become great readers, they must decode words at a reasonable speed so they don’t have to hold the meaning of the words in their memory for too long when figuring out the meaning of a sentence or paragraph [13]. When poor readers are unable to decode words at a reasonable speed they are required to spend extra time trying to decode, resulting in further stress on their ability to comprehend the text. [14].

Attention[edit | edit source]

When it comes to attention and reading, there is no doubt that attention is crucial to the understanding and overall comprehension of the text being read. Without attention, one cannot read. Teaching young students to read can often be challenging, as some don't have the ability to sit still for prolonged periods of time, or simply are not interested in the material they are supposed to be reading.

In order for a child to read, they must have a book open in front of them, they must be oriented towards the text.[15] Even getting some children to this point can be a great accomplishment, as some children simply do not have the attention span or capacity to focus on tasks such as this for so long.

In addition to having children pay attention to the actual book in front of them, it is necessary for them to make connections while they are reading in order for them to see how smaller pieces of the reading process relate to larger ones. A great deal of attention is needed for this as well, as there are often several instances in which a student can overlook a small point that will play a bigger part in their learning later on. Though older readers do not need to focus a lot of energy on the reading process, young readers must do so, simply because they haven't learned or practiced the process as much. Things such as eye movements and moving their eyes from left to right are included in this type of attention that is needed.[16]

Attention must also move systematically from word to word as they read, as well as making sure the words being read can be connected to the overall message of the text. In addition, attention needs to be shifted from images or illustrations to the text, and back again in order for all elements of the story to make sense.[17]

Reading Disabilities[edit | edit source]

As much as reading requires the child's ability to comprehend letters and words and draw on prior knowledge, the child must be taught these skills. However, some students will find difficulties in the learning process, which can in some cases be attributed to learning disabilities. There are several ways to effectively teach students the necessary means to developing literacy while working with any struggles they may be having.

Diagnosing Reading Difficulties[edit | edit source]

When it comes to disabilities, learning how to read can be a struggle for both teachers and students. A disability in learners can hinder the learning process, meaning teachers and instructors often have to adapt their teaching style to help the student grasp the information. Though the word “disability” can be viewed as a general term to mean a number of different things, each disability is different, and each can effect reading in a different way.

Oftentimes, the most difficult part of determining why a student is having troubles reading lies in diagnosing what the trouble is. In terms of diagnosis, there are three principles used to guide the process. First, an analysis must make a specific as possible diagnosis of the student's reading habits to discover which parts are not functioning properly. Second, the analysis has to be based upon any available and relevant facts. Last, a sense of open-mindedness must be maintained when looking over any data. [18] Though open-mindedness may not seem important in the scientific realm of things, it does make an impact on the diagnosis process, as the point of discovering a reading disability is not to prove or disprove a theory or method, but to find exactly what is troubling the student. In addition, it might be found that a student doesn't fall into the category of one specific learning disability, but perhaps show signs of struggling in more than one aspect. This is a case where open-mindedness plays a large part in the diagnosis and evaluation stages. Part of this is because though a child does have a reading disability, it doesn't necessarily need to fit a specific model or formula for what is considered a disability and what isn't.

Principles of diagnosis aside, there are six general steps in the diagnosis process:

1. "Measuring the reading achievement of the class or school" - Reading tests are administered to students to gauge the level of reading in each class, and deficiencies in scores can be seen.[19]

2. "Selecting the major reading problems for each grade" - Test scores are analyzed and the greatest problem for each grade is determined, and any student below the average needs attention and support.[20]

3. "Selecting pupils deficient in reading" - Students below the average are given attention.[21]

4. "Obtaining additional information about the pupils selected for individual diagnosis" - Information about the student's health, general intelligence and attitude are taken into account. Oftentimes factors such as these can have a large impact on the general leaning abilities of the student. Other factors such as perceptual span, the number and regularity of fixations, dyslexia, vocalization, and breathing habits should also be taken into account.[22]

5. "Determining the types of reading deficiencies" and 6. "Determining the causes of the defects in reading" can be grouped into one larger step, as the four preceding steps will help determine how and why the student is having difficulties learning.[23]

Though these steps can be used as guidelines in determining what a student may be having difficulties with, each case is unique and can be approached in other manners that may apply to that specific instance.

In diagnosing dyslexia, there are five tasks that help to determine if a child is in fact dyslexic or not: oral word and pseudoword reading, oral text reading, oral pseudoword text reading, oral word list reading, and spelling words and pseudowords.[24] In doing these tests, four types of reading speeds and four levels of reading and spelling accuracy are taken into account. If a child lands in the bottom 10th percentile of the scores for each tested task, it is found that they have deficient skills in that area of reading and comprehension. To be completely diagnosed with dyslexia, the child must score in the bottom 10th percentile in a minimum of three of the four accuracy tests, or in three of the four fluency tests, or in two of the accuracy tests and two of the fluency tests.[25]

In the past, learning disabilities were assessed through IQ tests and achievement scores on reading tests. If their IQ was found to be average but showed a low reading achievement score, the child was diagnosed as having a learning disability.[26] Known as the discrepancy model based procedure, this process of diagnosis was used in many schools, placing students in classrooms that could provide them with the assistance they need.

Today, the Component Model of Reading is used more often to help understand and diagnose reading and learning disabilities. There are three domains of the Component Model of Reading (CMR): cognitive, which includes the two components of word recognition and comprehension, psychological, which includes the components of motivation and interest, locus of control, learning styles and gender differences, and ecological, which includes the components of home and classroom environment and culture, parental involvement and dialect. [27] One thing to note is that the components of the cognitive domain can satisfy the condition of independence in a student, but the psychological and ecological domains do not do this as well.[28]

In a 2005 study regarding the effectiveness of the Component Model of Reading, it was found that IQ tests previously used to determine reading disabilities can only predict about 25% of variability in reading comprehension, whereas with the Component Model of Reading, 38-41% of variability can be found.[29]

Overall, the diagnosis of reading and learning disabilities is a process that has evolved over time, and is becoming more and more precise. Though there are multiple types of reading disabilities, each one should be approached with a sense of open mindedness, as well as a conscious awareness that each child and disability will be different. In terms of ways of diagnosis, the steps included in this section have proven to work, though they are subject to change in the future as educators learn more about intervention and how disabilities progress or change.

Types of Reading Difficulties and Disabilities[edit | edit source]

When discussing reading difficulties and disabilities, it is important to remember that there is a wide array of factors that can affect reading and comprehension, and not all students who experience trouble reading are diagnosed with a "reading disability". Sometimes students are not developmentally ready for leaning to read and struggle with understanding the linguistics of reading, while others come from cultural or linguistic backgrounds that don't match with the type of reading instruction taught in the school.[30] In addition, some students may have difficulty learning to read even with good instruction. This can be attributed to low general ability, meaning they struggle more with comprehension than the reading itself.[31]

Students can also have reading disabilities even if they are of average or above average intelligence, which is different than students who are poor readers. Speech problems are often paired with difficulties in writing and spelling, which in turn would hinder the student's ability to successfully read and comprehend what they're reading.[32]

One common reading difficulty lies in the phonics of a word, specifically when a student is unable to match the sounds of the letter to the visual symbol. In this case, the problem is central rather than sensory.[33] Word blindness, or dyslexia, is another common reading disability in which letters and words are mixed around in the student's brain, causing great difficulty in the comprehension of what is being read.[34]

Dyslexia is a reading deficiency that runs in families. The risk of a child developing dyslexia increases to 40% if a parent or relative also has the disability.[35]

Left handed students often have difficulty learning to read, as reading from left to right is natural for right handed students - they are used to leading away from the centre of the body rather than to it, which is the opposite for left handed students.[36]

Slow, silent reading can be caused by visual defects as well as a narrow span of recognition and dyslexia, while poor reading comprehension of slow reading can be caused by an inability to focus, organize main ideas, or lack of attention.[37] However, though reading comprehension can be hindered by a lack of attention, too much attention or focus on single words can also cause problems. If a student focuses too much on individual words, they can be unable to bring a sentence together as a whole.

In terms of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), it is found that 8% to 20% of students have the disorder, but only 3% to 7% show severe enough symptoms that they are given a clinical diagnosis and are provided with special education intervention and services.[38] Though ADHD does not always mean that a student has a reading disability, it can often coincide with one, in most cases causing students to misinterpret texts, or have general comprehension issues regarding common connections in what is being read.

Implications for Teaching[edit | edit source]

As with any student who is struggling with any subject matter, teachers and learning aids need to make changes in teaching styles and material to help make the material learnable. One approach is the Reading Recovery method, which was developed in New Zealand. This method consists of four steps:

1. "Children are assessed on a variety of literacy tasks, such as their ability to identify letters, read words, write, and do oral reading, as well as on their literacy knowledge and strategies"

2. "A series of 30-minute daily tutorials in which a Reading Recovery teacher works one-on-one with an individual student."

3. "Standardized sessions that provide a systematic set of activities, including having the child practice letters and words, read from short books, and produce short compositions that are cut up and re-read."

4. "A systematic process of staff development in which teachers are trained by Reading Recovery trainers."[39]

This level of scaffolding is both practical and efficient in propelling the learning of students, and provides a high level of support for both students and teachers.

In a 2005 study conducted by Robert Schwartz, the Reading Recovery program was examined in terms of the effectiveness in aiding first grade students. In this study, 47 Reading Recovery teachers in 14 states sent information of 107 students, 53% of which were male and 47% of which were female. The students were paired with a Reading Recovery teacher who led them through the program, which includes daily tutorials that span the length of 30 minutes that are targeted toward structured activities that include practicing letters and words, reading short books, producing small pieces of writing that are later divided up and re-read. At the end of the study, 65% of students “graduated” the program, 16% were recommended for further help, and 16% did not complete the program. This can be compared to the national Reading Recovery data: 56% of students graduated, 15% were recommended for further help, 19% were labelled as incomplete, 5% “moved” and 4% were labelled as “none of the above”.[40]Reading Recovery has proven to be a very successful program in regards to rehabilitation and intervention. One interesting aspect of the Reading Recovery program is that though it's been around since the 80's, the system and process is still effective, and hasn't needed to undergo any major changes. A testament to the success of the program is that is it used internationally in English speaking countries, and has a high success rate.

As with any situation in which a student is struggling, teaching methods and procedures must be adjusted to adapt to the struggle of the child. Intervention of reading disabilities is very important in the stages of learning to read, as a problem developed with learning to read can plague a student throughout their entire lives if not caught soon enough. This is exactly why programs such as Reading Recovery and the help of teachers are so important in the process of learning to read. Though the help of SEA's and other support workers can greatly benefit the students and help take some of the load off of teachers, it is still important to remember that each child does need to have a unique learning plan catered to what they need and don't need assistance with.

Though not all students are diagnosed with a reading disability, it is not uncommon for students to struggle with material taught in class. Sometimes this can be attributed to an undiagnosed disability. In the case of an undiagnosed student, or a student who is not disabled but still faces challenges with learning, intervention and understanding can play a large part in the future development for the child.

Stages of Reading[edit | edit source]

Like learning any other thing in life, learning to read requires steps or stages. When children start to learn to read there are three main stages that they will all go through. Children start off learning to read by not being able to decode any words (pre-alphabetic stage), they then start to use phonic cues and other reading strategies (partial alphabetic stage), and finally get to the point where they are able to distinguish between similar spelt words and are able to learn new words while making connections (full alphabetic stage) [41]. Reading develops in multiple dimensions before individuals reach conventional literacy. Each of these stages is described as young children move from displaying very little literacy-related behaviours to eventually being able to systematically decode language.

Pre-Alphabetic Stage[edit | edit source]

The pre-alphabetic stage consists of children who know quite a bit about literacy but don’t know how to read any words. Children at this stage have no alphabetic knowledge which is why the stage is called pre-alphabetic stage. Children however do know a lot of words, can speak in full sentences, and have conversations with others, but are just not able to read any actual words. However, they may say a word by looking at the symbol associated with it. For example, reading the word ‘McDonald’s’ by looking at the big ‘M’ or saying the word 'dog' by looking at a picture of one. Children have no recognition of the word ‘McDonald’s’ or the word 'dog' nor will they be able to read the word once the picture is taken away. Children are simply responding to their environment and not to the print [42]. Despite children knowing quite a bit of words and being able to say full sentences they are just not able to read the words or any print on their own. Another type of group in this stage try “linking a word’s look with its pronunciation and meaning” [43]. However, the memory demands of reading in this way become very overwhelming and exhausting for children and they soon try relying more on phonetic information while reading [44].

Partial Alphabetic Stage[edit | edit source]

Children enter the partial alphabetic stage when they learn the names or sounds of the alphabet and then use this knowledge to read words [45]. This is the stage where the actual reading starts to occur. Children are no longer just looking at the images and reading the word, they are actually trying to read the print. They now have knowledge of the letters in the alphabet and are using this knowledge to help them read words. Children in this stage generally focus more on the first and last letters of words, for example, the letter s and n to read spoon [46]. When children are asked to write down words they tend to write down the letters whose sound they can hear when pronouncing the word. For example, children might write the word giraffe as jrf [47]. Children's reading at this stage is only partial because they are simply just looking at some of the letters in words and usually only some sound for pronunciation [48].

To better understand the difference of pre-alphabetic stage readers and partial alphabetic stage readers, a study was conducted by Ehri and Wilce in 1985. This study tested kindergartners by separating them into the two different stages mentioned above. Each stage was given several practice trials to learn to read two kinds of spellings. One kind involved visual spellings with varied shapes but no relationship to sounds, so for example, mask spelled uHo. The other kind involved phonetic spelling that had letters represent some sounds in the words, so for example, mask spelled MSK.

The results were that the pre-alphabetic stage readers learned to read visual spellings a lot easier than the phonetic spellings [49]. Ehri explained that this confirmed their idea that pre-alphabetic stage readers depend on visual cues because they lack knowledge of letters. The partial alphabetic stage readers displayed the opposite pattern and were able to use letter-sound cues to remember the words.

Full Alphabetic Stage[edit | edit source]

When children are able to learn sight words by forming complete connection between letters in spelling and phonemes in pronunciations, they have moved onto the full alphabetic stage [50]. In the partial alphabetic stage children will write down words with only the letters they can clearly hear when pronouncing the word. However, in the full alphabetic stage children are now able to decode unfamiliar words when reading, they can invent spellings that represent all the phonemes, and are able to remember the spelling of words a lot better [51].

To show the difference in the phases of reading a study was conducted by Ehri and Wilce in 1987. This study was done to show the differences in sight word learning between full and partial stage readers [52]. For this study, kindergartners who were already in the partial alphabetic stage were randomly selected. They then were randomly assigned to a treatment or a control group. The treatment group then received training to become full alphabetic stage readers by having them practice reading similarly spelled words. This required processing all the grapheme-phoneme relations in the words to read them correctly. The control grouped received no training what so ever and remained as partial stage readers. Following this, both groups of kindergartners got practice learning to read a set of fifteen words over several trials. All the words in the list had similar spellings which made it harder for children to learn by remembering partial cues. The list of words included words such as spin, stab, stamp, or stand. Before the study none of the children could read more than two of these words prior to training.

The results of the study showed huge differences between the two groups of kindergartners. Full-alphabetic stage readers learned to read most of the words in the list in three trials but the partial alphabetic stage readers never even reached this level of learning [53]. The study did say that the reason for difficulty for the partial alphabetic stage readers is due to them confusing similarly spelled words. Which goes to show the advantage readers get when they can form full connections to retain sight words in memory [54].

It is important to note how just being one stage behind in reading can cause such a huge difference in the results. Just by being at the full alphabetic stage the kindergartners were able to read the similarly spelled words in three trials whereas the partial alphabetic stage kindergartners had so much trouble doing so. It goes to show the importance of each reading stage and how important it is for teachers to make sure students are ready to go onto the next stage. Teachers need to be sure that students have learnt everything they need in the previous stage to help them pass the next one.

Consolidated Stage[edit | edit source]

Children get to this final stage of reading when they have retained more sight words in their memory and are familiar with letter patterns [55]. Children are now familiar with letter patterns that appear repeatedly in different words and the grapheme-phoneme connections begin to get consolidated into larger units [56]. For example, words such as printing is learned more easily now because fewer connections are required to secure the word in memory and the word is no longer being processed as many separate letter-sound connections but as two syllable sized chunks [57].

Implications for Teaching[edit | edit source]

The English language is not perfect and therefore it can have one letter represent one sound, two or more letters represent that one sound, a silent final vowel can change the sound of the medial vowel, and many words contain letters that have no sound [58]. When teachers are starting to teach their students how to read they should be aware of the interconnection between letters and sounds and know the different stages children go through when they are developing their literacy skills. Throughout the three alphabetic stages, teachers should focus on decoding and vocabulary as the mastery as these dimensions are vital to successful reading [59]. Children need to be able to decode words or in other words be able to think about letter and sound relationships and correctly pronounce written words. Games can be used to teach children the correct pronunciation of letters and their sounds. Having children hear the different sounds of letters with the letter in front of them will help them understand better. Since beginner readers are visual learners, pictures might help them understand the relationship between letters and the sound. For example, a teacher may put up a picture of bat and write on the board the word bat but skipping the first letter. Now the teacher can ask the students what the first letter might be by repeatedly saying the word bat and helping the students sound it out. It is important for children to decode and fluently read words, but it is also vital that children understand the meaning of specific contextual words [60]. When children can read and understand the meaning of the words they are able to truly comprehend a text [61]. Teachers should help children in discovering the meaning of words found in a text by having them place words connected to each other in specific categories, create connected categories of words, pointing out relationships between words, using dictionaries or thesauruses to extend word meaning, and having students self-select words for vocabulary study and stating specific reasons for choosing these words [62].

Teaching to Read[edit | edit source]

There is often great importance placed on literacy and the skill of reading, and so teachers may feel pressured to find the best approaches or methods for teaching their students how to read. Deciding which areas to focus on can be challenging when teaching beginning readers. Ideally, reading instruction should touch on each of the foundations of language, as well as the benefits of learning to read. Over the course of the history of reading instruction, there have been numerous controversies about which methods are the best to teach children to read[63]. In 1967, Jeanne Chall grouped reading methods into two categories that are still useful in understanding the divide on reading instruction: code-emphasis methods and meaning-emphasis methods. Code-emphasis methods focus on decoding and learning letters and sounds, while meaning-emphasis methods focus on making meanings and using one’s general knowledge store[64]. The following approaches to teaching reading are separated by their methodology, but today, models of reading strive for a balance between the two types of reading methods because they are both recognized as essential for learning to read. Reading and literacy development have many different dimensions, but we also must not forget the importance of teaching children that reading can be enjoyable.

Phonics-Based Approach[edit | edit source]

A phonics-based approach to teaching reading is a type of code-emphasis method. Primary goals include making sure children can: understand letter-sound correspondences, automatically recognize familiar words, and decode unfamiliar words[65]. Researchers advocating for a more phonics-based approach believe that phonemic awareness is a requirement for learning to connect alphabetic symbols to their sounds, and that these letter-sound connections are required for learning to identify individual words and learning to read in general[66]. From a logical standpoint, learning letter-sound correspondences may seem the most salient for beginning readers, especially since words are made up of combinations of letter-sound correspondences. Within a phonics-based approach, there are two types of instruction: an explicit phonics approach and an implicit phonics approach. In an explicit phonics approach, sounds are associated with the letters by themselves, and then are blended together to form words[67]. In the classroom, a teacher might directly tell students the sound represented by an individual letter. Once students have learned a few letter-sound correspondences, they begin to learn to read by blending the sounds together[68]. The main strategy used for identifying words in an explicit phonics approach is based on the student’s knowledge of letter-sound correspondences[69]. When a student encounters an unfamiliar word, they are encouraged to sound it out and they are not directed to the context of the word until after the word has been identified[70]. In this case, context is only a metacognitive strategy used to understand the text as a whole[71]. In an implicit phonics approach, sounds of letters are identified in the context of whole words rather than letters in isolation[72]. During instruction, the teacher might write the word hand on the board, and underline the letter h. Then, the teacher would have the students say “hand” to elicit from them that h makes the sound /h/[73]. In addition, the context of the word and picture clues may be used to sound out unfamiliar words. A common problem that has been identified in using context to teach letter-sound correspondences is that some students fail to learn these correspondences because they are unable to split words into their individual sounds, since they lack the skills needed to infer sounds from a whole word[74]. Evidence from research indicates that a large majority of poor readers are deficient in alphabetic coding and phonemic awareness [75]. As stated earlier, ideal reading instruction should involve both code-emphasis methods and meaning-emphasis methods. As such, more people are against over-emphasis of phonics and prescriptive teaching methods than there are people against phonics instruction itself[76].

A study by Maddox and Feng (2013) compared the efficacy of whole language reading instruction versus phonics instruction for improving students’ reading fluency and spelling accuracy. The researchers hypothesized that explicit phonics instruction would have a more positive effect on students’ reading fluency and spelling accuracy than whole language instruction, and that the students receiving explicit phonics instruction would show greater gains in reading fluency and spelling accuracy than students receiving whole language instruction. Twenty-two first graders from one classroom were randomly assigned to either the experimental group or the control group. The experimental group became the phonics group and received explicit phonics instruction, while the control group became the whole language group and did not receive explicit phonics instruction. With the experimental group, the teacher taught phonics patterns and the group practiced segmenting, coding, blending and working with these patterns, but did not read any stories. With the control group, the teacher read the students fourteen stories from the Raz-kids reading program; the words in the stories contained the same phonics patterns as those taught in the phonics group and the students focused on picture walks, story predictions, and meaning of vocabulary. Both groups met with their teacher (who was also one of the experimenters) for twenty minutes, five days a week, over a span of four weeks. Before the training sessions began, students’ pretest scores were gathered using the Aimsweb Reading Curriculum Based Measure (RCBM) and the Aimsweb Spelling Curriculum Based Measure (SCBM). After the four weeks of training, the same tests were administered to the students again to calculate posttest scores to measure changes in reading fluency and spelling accuracy. The results indicated no statistically significant differences in reading fluency or spelling accuracy of either group. The phonics group had higher reading scores on average and increased their reading fluency by 8.00 points compared to the whole language group, who increased their reading fluency by 4.09 points. Data for spelling accuracy showed the phonics group had positive results with an increase in 1.00 point while the whole language group regressed with a decrease of -0.27 points. A direct comparison indicates the phonics group made greater gains in both reading fluency and spelling accuracy.[77]

Phonemic Awareness[edit | edit source]

How does phonemic awareness affect learning to read? Phonemic awareness is described as the ability to focus on and manipulate phonemes in spoken words. Phonemes are the smallest units that make up spoken language, and are combined to form syllables and words,[78] thus, phonemic awareness is a code-emphasis method. Research has posited that sight-reading words from memory requires phoneme segmentation skills, and that phonemic awareness is thought to help children write words by enabling them to invent letter-sound spellings or retrieve spellings from memory[79].

A study by Castle, Riach and Nicholson (1994) was done with the aim of determining whether training in phonemic awareness would get children off to a better start in reading and spelling, even if they were already being instructed within a whole language program. The experiment was done with children in New Zealand during their first few months of school, during the time they were just learning to read and write. Thirty 5-year-olds from three different schools were divided and matched into one experimental group and one control group. The experimental group had 20-minute training sessions twice a week for 10 weeks, totalling 6.7 hours in overall training time. The topics covered during these sessions were chosen with the purpose of increasing phonemic awareness, including phoneme segmentation, phoneme substitution, phoneme deletion, and rhyme. The control group had the same amount of instructional time, but the children were involved in process writing activities as part of the whole language approach in New Zealand schools, in which children wrote their own stories and invented their own spellings of words. A series of pretests were administered before the training sessions began, including: Roper’s measure of phonemic awareness, a Wide Range Achievement of Spelling test, an experimental spelling test, and a diction test. These same tests were also administered as posttests after the training sessions were completed. The results from the study showed significant gains for both groups in phonemic awareness, but there was a considerable difference between the experimental and control groups that indicates that the training program used in the study was effective in improving phonemic awareness skills. There was also a significant difference between the groups on two of the spelling tests (Wide Range Achievement of Spelling test and experimental spelling test), showing that improvement in phonemic awareness skills leads to better spelling skills. In conclusion, the findings of the study suggest that the ability to link letters and their sounds is associated with spelling progress, and that phonemic awareness promotes spelling acquisition[80].

It is important to note that the impact of phonemic awareness instruction is greatest in the preschool and kindergarten years, and may become smaller beyond first grade[81]. As students move beyond first grade, phonemic awareness skills becomes less important than the need to learn spelling patterns[82]. Explicit instruction in phonemic awareness may not be as effective for older students, however; it may be effective for children who have not made normal reading progress and students with reading disabilities, thus, phonemic awareness skill instruction can help with these students’ reading and spelling difficulties[83].

Whole Language Approach[edit | edit source]

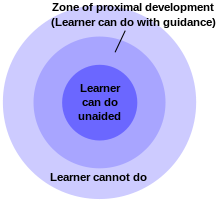

In a whole language approach, literacy is viewed as a top-down process[84]. The whole language approach is a philosophy that emphasizes reading words and sentences are of greater importance than learning the sounds and phonemes that make up words. Letter sound-correspondences are not taught independently of reading, and so it is a type of meaning-emphasis method. Students are engaged with language as a whole, rather than separating out the parts and practicing each one on its own[85]. Reading is meant to occur naturally, as when children first learned to speak: with very little direct instruction and lots of encouragement[86]. By experiencing the wholeness of reading, only then do students learn the subparts of words[87]. A whole language approach is very much a context-driven process, and words are not presented out of context[88]. In order to make sense of the text at hand, students are meant to use their store of accumulated knowledge, illustrations, phonetic strategies and prior experiences to make sense of the text and any unfamiliar words[89]. Teachers who support a whole language approach often use “real books” rather than basal readers (often seen in code-emphasis methods) because they promote reading fluency and making meanings[90]. Furthermore, it is stressed in a whole language approach that the process of learning is not always smooth and certain, and that students must take ownership and responsibility for their learning goals[91]. The whole language approach is often looked at from a Vygotskian perspective: teachers are mediators who make learners’ transactions with the world possible[92]. According to Vygotsky, learning is a social interaction, and children need to converse with others in order to exchange and form meanings [93]. As such, the whole language approach to reading instruction flourishes through all kinds of social interaction because learners can more effectively solve problems when they are collaborating on the same problems and developing the same skills[94]. When students work together, their discussion can often lead to not only solving the problem at hand, but also forming new meanings and accumulating new knowledge from information derived from collaboration. Vygotsky also stated that literacy experiences should be structured so that they are necessary for something, that is, there is a purpose for learning how to read and write[95]. Using examples in class that are relatable or have a parallel comparison to students’ experiences outside the classroom can increase reading motivation[96]. One other Vygotskian model for reading instruction using a whole language approach is to work within a student’s zone of proximal development, which is a person's area of learning between what they can do alone and what they can do with help. During reading, asking students questions about the language or for clarification can build on skills they already posses[97]. Asking students questions about the material and fostering meaning making can have a positive effect on reading comprehension. Research suggests that when real reading is considered the main element of whole-language reading instruction, the approach is beneficial to reading comprehension tests[98]. After all, reading comprehension is a main goal of reading instruction.

Manning and Kamii’s study (2000) on reading and writing tasks in kindergarten students compared the effectiveness of whole language versus isolated phonics instruction. Thirty-eight children from two kindergarten classes at one school in the United States were examined. The teacher of one class identified as a whole language teacher, and the other as a phonics teacher. In the phonics classroom, the students had daily phonics worksheets and oral-sound training, and often used flashcards to practice sight words and letter-sound correspondences. There were posters that displayed various phonics rules, marked with symbols to indicate long or short vowel sounds. In the whole language classroom, children did a lot of shared reading and writing, such as independent journal writing and also group writing activities. Books were read aloud by the teacher for over an hour each day, spread out over the day. All the children were interviewed individually five times throughout the year, where they were asked to write eight words and then read two to four sentences. The researchers then scored the students according to their level of writing and ability to identify a word in a given sentence. Results showed that although the whole language group started out the year at a lower level, many more children ended the year at a higher level than the phonics group. In the phonics group, there were more instances of regression, and overall advanced less and became more confused during their kindergarten year[99].

Schema Theory[edit | edit source]

Schema theory is an explanation of how readers use their prior knowledge to comprehend text[100]. The term schema (plural: schemata) was first introduced in psychology to describe a mental framework that organizes a person’s knowledge, and was then later used in reading instruction to describe the role that students’ prior knowledge plays in reading comprehension[101]. According to schema theory, people organize everything they know into schemata[102]. Everyone’s schemata are individualized, and the more elaborated a person’s schema is for any specific topic, the more easily they will be able to learn new information in that topic area[103]. A person’s existing knowledge structures are malleable and constantly changing[104]; when a person learns new information, their pre-existing schema may need to adjust to accommodate this new information. In regards to reading, the main idea of schema theory is that written text does not carry meaning alone; rather, the text provides guidance for how readers should retrieve or construct meaning from previously existing knowledge structures[105]. In addition to having schemata for content, learners also have schemata for reading processes and different kinds of text structures[106]. Understanding the text is a reciprocal and interactive process between the reader’s prior knowledge and the actual text because effective comprehension requires the ability to relate prior knowledge to the text[107]. Schema theory has two kinds of processing during reading comprehension: bottom-up processing is schema activation (when textual stimuli signal recall of relevant schemata) through specific information in the text, while top-down processing starts with general knowledge and moves down towards more specific details, and as more stimuli are presented, the reader’s specific schemata pertaining to the text can be activated[108]. These two types of processing occur simultaneously and interactively in order to comprehend text[109].

Research suggests that when readers activate prior knowledge by previewing the text, they use schemata immediately when they start reading and focus instead on new information, with the aim of building connections between old and new information[110]. Without existing schema regarding the structure or content of the text, reading comprehension will not occur[111]. Due to the importance of pre-existing knowledge, teachers can build on and activate students’ schema prior to reading[112]. Previewing the text can include brainstorming or group discussions, or even reviewing strategies and skills for reading the text. It is also important to note that differences and students’ schemata relate in differences in reading comprehension, but previewing text also allows a reader to realize in advance that they have knowledge of the subject, increasing the student’s self-efficacy for that reading task[113].

A study of Iranian students examined whether schema activation through pre-reading activities has an effect on reading comprehension of culturally based texts. The subjects consisted of seventy-six English as a Foreign Language (EFL) students either majoring in English Literature, or majoring in Teaching English as a Foreign Language (TEFL). All the participants were sophomore students in their fourth semester at the Islamic Azad University of Kerman in Iran. To make sure all students were of the same English proficiency, they were categorized from a basic to upper-intermediate level of English based on their results on the Oxford Placement Test. Participants were then separated into two groups: one experimental group and one control group. The researchers tested two null hypotheses: the first, that there would be no significant difference between the mean pretest and mean posttest scores of the experimental group after schema activation; and the second, that there is no relationship between the pretest and posttest scores of the experimental group when the students’ schemas are activated through pre-reading activities. During the procedure, both the experimental and control groups were administered a reading comprehension test about the origins and customs of Halloween as a pretest. The topic was chosen because the holiday is culturally loaded, and so students from another country may have difficulties understanding it. Then, the experimental group had two training sessions of schema activation with a researcher– these sessions included pre-reading activities, previewing, pre-teaching vocabulary, and looking at pictures to make the students more familiar with Halloween customs. The group was then asked to talk about what they knew about Halloween, and this served as a basis for group discussion. During the training sessions, the researcher asked the group questions about new vocabulary word, and provided synonyms and definitions when necessary. The experimental group was then given the same reading comprehension test as a posttest two weeks later. The control group was only administered the initial pretest, and did not have any training sessions or a posttest. The results showed that both null hypotheses were rejected, and that both groups scored about the same on the pretest – the experimental group with a mean score of 16.42 and the control group with a mean score of 16.57 – but after the experimental group’s training sessions, their posttest mean score increased to 18.70. The researchers also found a significant relationship between the pretest and posttest scores of the experimental group. In conclusion, as the experimental group received more background knowledge, reading comprehension was enhanced, and the researchers strongly believe that the results and implications of the study are applicable to other less culturally bound materials. Teacher guidance is crucial for helping students connect new information to existing schemas, and spending time on schema activation activities leads to better student performance[114].

Assessing Reading Progress[edit | edit source]

When children start school, one of the very first things they start to learn is reading. Formally learning to read starts in kindergarten and continues throughout our lifetime. When children are learning to read it is important to give them feedback and assess them along the way to see how they are doing. In order to gauge the success and improvement of a student's reading skills, there are some frequently assessed markers to determine one's reading progress: phonemic awareness, letter knowledge, and oral reading fluency [115]. Before children learn to print, they need to be aware of how the sounds of the letters in words work. Phonemic awareness is basically assessing just that, children need to have the ability to notice, think about, and manipulate the phonemic segments of spoken words [116]. If children are not aware of the sound structure of language they will be not be able to attend to the separate sounds in spoken words and thus will not be able to establish letter-sound correspondences [117]. It is believed that this letter-sound link is a foundational skill in decoding, and are important early skills in literacy [118]. Letter knowledge is measured by children’s ability to name upper and lower case letters and know the sounds of each of the letters in the alphabet [119]. This is key for children to know because it is only when they understand the letters and their sounds that they can start to read. While reading, children have to know how to sound out words, decode them, and pronounce them and this is only possible if they have mastered the letters and their sounds. The third type of assessment used to measure early reading progress is known as reading fluency. This is basically trying to measure children’s ability to read quickly, accurately, and with expression [120]. This type of assessment is controversial for some people because they don’t believe that by reading quickly children have progressed. Reading quickly and accurately isn’t the real purpose of reading, it's understanding and recalling what you have read that is important [121].

Effective assessment should be an ongoing process and shouldn’t just stop after children can quickly read a text and understand it. Which is why there are some authentic assessment measures that teachers are able to use to determine students’ skills and learning and to inform present and future instruction [122]. Teachers are able to use assessments such as oral and written story retellings which will informally measure students’ reading comprehension, literacy portfolios can be used to showcase student’s oral and written processes, products, and skills, and checklists can be used to help the teacher’s observations of students and to determine students’ literacy needs and growth [123].

Assessing the reading progress of students’ is important and makes teachers aware of what stage their students’ are at. This will help teachers to better assist their students’ needs. Assessing students has a lot of benefits to it but teachers should always be aware that assessing isn’t everything and not all students can be assessed at the same time or in the same way.

Glossary[edit | edit source]

Bottom-up processing: An approach to information processing that involves piecing together smaller pieces of information and building up to bigger concepts.

Code-emphasis methods: Approaches to reading that stress the importance of decoding letters and words, and letter-sound correspondences.

Discourse: Structured, coherent sequences of language in which sentences are combined into higher order units, such as paragraphs, narratives, and expository texts, i.e., conversations [124].

Explicit phonics approach: Reading instruction in which the sounds associated with letters (letter-sound correspondences) are identified first independently, then are later blended together to form words.

Full Alphabetic Stage: Readers who, as they conclude the early stages of reading, can identify the separate sounds in words and understand that spellings correspond to pronunciation [125].

Implicit phonics approach: Reading instruction in which the sounds of letters are identified within the whole word rather than independently.

Meaning-emphasis methods: Approaches to reading that focus more on making meanings from the words and using one's general knowledge store.

Partial Alphabetic Stage: Readers who, in the early stages of reading, read by associating some but not all of words’ letters with sounds [126].

Phoneme: The smallest unit of sound that makes up a word.

Phonemic Awareness: The ability to identify and manipulate the individual phonemes in a word.

Pragmatics: The meanings, messages, and uses of language [127].

Pre-Alphabetic Stage: It is the stage when children know quite a bit of literacy but do not know how to read any words.

Schema:The idea of a mental framework that helps us organize knowledge and the relationships between these pieces of information.

Schema activation:The process by which textual stimuli signal the recall of relevant schemata from memory for the present reading task.

Semantics: The study of words and their meanings [128].

Syntax: Ways words in a language are grouped into larger units, such as in phrases, clauses, and sentences [129].

Top-down processing: An approach to information processing that involves using general knowledge to fill in what is known and working down towards smaller details.

Zone of proximal development: A concept created by Vygotsky that describes the area of learning between what a student is capable of doing by themselves, and what they can do with help, i.e., from a teacher, parents, or caregiver.

Recommended Readings[edit | edit source]

Bukowiecki, E. M. (2007). Teaching children how to read. Kappa Delta Pi Record, 43(2), 58-65. doi: 10.1080/00228958.2007.10516463

Ehri, L. C. (2005). Learning to read words: Theory, findings, and issues. Scientific Studies of Reading, 9(2), 167-188. doi: 10.1207/s1532799xssr0902_4

Hempestall, K. (2005). The whole language‐phonics controversy: A historical perspective. Australian Journal of Learning Disabilities, 10(3-4), 19-33. doi: 10.1080/19404150509546797

Tracey, D.H., & Morrow, L.M. (2012). Lenses on Reading, Second Edition : An Introduction to Theories and Models. Guilford Press.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Bruning, R.H., Schraw, G.J., & Norby, M.M. (2011). Cognitive Psychology and Instruction (5th ed). Pearson.

- ↑ Bruning, R.H., Schraw, G.J., & Norby, M.M. (2011). Cognitive Psychology and Instruction (5th ed). Pearson.

- ↑ Swanson, H. L., & Ashbaker, M. H. (2000). Working memory, short-term memory, speech rate, word recognition and reading comprehension in learning disabled readers: Does the executive system have a role? Intelligence, 28(1), 1-30. doi:10.1016/S0160-2896(99)00025-2

- ↑ Swanson, H. L., & Ashbaker, M. H. (2000). Working memory, short-term memory, speech rate, word recognition and reading comprehension in learning disabled readers: Does the executive system have a role? Intelligence, 28(1), 1-30. doi:10.1016/S0160-2896(99)00025-2

- ↑ Verhoevan, L., Reitsma, P., & Siegel, L. S. (2011). Cognitive and linguistic factors in reading acquisition. Reading and Writing, 24(4), 387-394. doi:10.1007/s11145-010-9232-4

- ↑ Verhoevan, L., Reitsma, P., & Siegel, L. S. (2011). Cognitive and linguistic factors in reading acquisition. Reading and Writing, 24(4), 387-394. doi:10.1007/s11145-010-9232-4

- ↑ Verhoevan, L., Reitsma, P., & Siegel, L. S. (2011). Cognitive and linguistic factors in reading acquisition. Reading and Writing, 24(4), 387-394. doi:10.1007/s11145-010-9232-4

- ↑ Verhoevan, L., Reitsma, P., & Siegel, L. S. (2011). Cognitive and linguistic factors in reading acquisition. Reading and Writing, 24(4), 387-394. doi:10.1007/s11145-010-9232-4

- ↑ Verhoevan, L., Reitsma, P., & Siegel, L. S. (2011). Cognitive and linguistic factors in reading acquisition. Reading and Writing, 24(4), 387-394. doi:10.1007/s11145-010-9232-4

- ↑ Bruning, R.H., Schraw, G.J., & Norby, M.M. (2011). Cognitive Psychology and Instruction (5th ed). Pearson.

- ↑ Bruning, R.H., Schraw, G.J., & Norby, M.M. (2011). Cognitive Psychology and Instruction (5th ed). Pearson.

- ↑ Bruning, R.H., Schraw, G.J., & Norby, M.M. (2011). Cognitive Psychology and Instruction (5th ed). Pearson.

- ↑ Bruning, R.H., Schraw, G.J., & Norby, M.M. (2011). Cognitive Psychology and Instruction (5th ed). Pearson.

- ↑ Bruning, R.H., Schraw, G.J., & Norby, M.M. (2011). Cognitive Psychology and Instruction (5th ed). Pearson.

- ↑ Bruning, R.H., Schraw, G.J., & Norby, M.M. (2011). Cognitive Psychology and Instruction (5th ed). Pearson

- ↑ Bruning, R.H., Schraw, G.J., & Norby, M.M. (2011). Cognitive Psychology and Instruction (5th ed). Pearson.

- ↑ Bruning, R.H., Schraw, G.J., & Norby, M.M. (2011). Cognitive Psychology and Instruction (5th ed). Pearson.

- ↑ Brooks, F. D. (1926). How to diagnose reading deficiencies. In , The applied psychology of reading: With exercises and directions for improving silent and oral reading (pp. 168-185). New York, NY, US: D Appleton & Company. doi:10.1037/14870-012

- ↑ Brooks, F. D. (1926). How to diagnose reading deficiencies. In , The applied psychology of reading: With exercises and directions for improving silent and oral reading (pp. 168-185). New York, NY, US: D Appleton & Company. doi:10.1037/14870-012

- ↑ Brooks, F. D. (1926). How to diagnose reading deficiencies. In , The applied psychology of reading: With exercises and directions for improving silent and oral reading (pp. 168-185). New York, NY, US: D Appleton & Company. doi:10.1037/14870-012

- ↑ Brooks, F. D. (1926). How to diagnose reading deficiencies. In , The applied psychology of reading: With exercises and directions for improving silent and oral reading (pp. 168-185). New York, NY, US: D Appleton & Company. doi:10.1037/14870-012

- ↑ Brooks, F. D. (1926). How to diagnose reading deficiencies. In , The applied psychology of reading: With exercises and directions for improving silent and oral reading (pp. 168-185). New York, NY, US: D Appleton & Company. doi:10.1037/14870-012

- ↑ Brooks, F. D. (1926). How to diagnose reading deficiencies. In , The applied psychology of reading: With exercises and directions for improving silent and oral reading (pp. 168-185). New York, NY, US: D Appleton & Company. doi:10.1037/14870-012

- ↑ Eklund, K. M., Torppa, M., & Lyytinen, H. (2013). Predicting reading disability: Early cognitive risk and protective factors. Dyslexia: An International Journal Of Research And Practice, 19(1), 1-10. doi:10.1002/dys.1447

- ↑ Eklund, K. M., Torppa, M., & Lyytinen, H. (2013). Predicting reading disability: Early cognitive risk and protective factors. Dyslexia: An International Journal Of Research And Practice, 19(1), 1-10. doi:10.1002/dys.1447

- ↑ Aaron, P. G., Joshi, R. M., Gooden, R., & Bentum, K. E. (2008). Diagnosis and treatment of reading disabilities based on the component model of reading: An alternative to the discrepancy model of LD. Journal Of Learning Disabilities, 41(1), 67-84. doi:10.1177/0022219407310838

- ↑ Aaron, P. G., Joshi, R. M., Gooden, R., & Bentum, K. E. (2008). Diagnosis and treatment of reading disabilities based on the component model of reading: An alternative to the discrepancy model of LD. Journal Of Learning Disabilities, 41(1), 67-84. doi:10.1177/0022219407310838

- ↑ Aaron, P. G., Joshi, R. M., Gooden, R., & Bentum, K. E. (2008). Diagnosis and treatment of reading disabilities based on the component model of reading: An alternative to the discrepancy model of LD. Journal Of Learning Disabilities, 41(1), 67-84. doi:10.1177/0022219407310838

- ↑ Aaron, P. G., Joshi, R. M., Gooden, R., & Bentum, K. E. (2008). Diagnosis and treatment of reading disabilities based on the component model of reading: An alternative to the discrepancy model of LD. Journal Of Learning Disabilities, 41(1), 67-84. doi:10.1177/0022219407310838

- ↑ Bruning, R.H., Schraw, G.J., & Norby, M.M. (2011). Cognitive Psychology and Instruction (5th ed). Pearson.

- ↑ Bruning, R.H., Schraw, G.J., & Norby, M.M. (2011). Cognitive Psychology and Instruction (5th ed). Pearson.

- ↑ Bruning, R.H., Schraw, G.J., & Norby, M.M. (2011). Cognitive Psychology and Instruction (5th ed). Pearson.

- ↑ Hoillingworth, L. S. (1923). Reading. In , Special talents and defects: Their significance for education (pp. 57-97). New York, NY, US: MacMillan Co. doi:10.1037/13549-004

- ↑ Hoillingworth, L. S. (1923). Reading. In , Special talents and defects: Their significance for education (pp. 57-97). New York, NY, US: MacMillan Co. doi:10.1037/13549-004

- ↑ Eklund, K. M., Torppa, M., & Lyytinen, H. (2013). Predicting reading disability: Early cognitive risk and protective factors. Dyslexia: An International Journal Of Research And Practice, 19(1), 1-10. doi:10.1002/dys.1447

- ↑ Dearborn, W. F. (1932). Difficulties in learning. In W. V. Bingham, W. V. Bingham (Eds.) , Psychology today: Lectures and study manual (pp. 186-194). Chicago, IL, US: University of Chicago Press. doi:10.1037/13342-021

- ↑ Brooks, F. D. (1926). How to diagnose reading deficiencies. In , The applied psychology of reading: With exercises and directions for improving silent and oral reading (pp. 168-185). New York, NY, US: D Appleton & Company. doi:10.1037/14870-012

- ↑ Zentall, S. S., & Lee, J. (2012). A reading motivation intervention with differential outcomes for students at risk for reading disabilities, ADHD, and typical comparisons: 'Clever is and clever does'. Learning Disability Quarterly, 35(4), 248-259. doi:10.1177/0731948712438556

- ↑ Bruning, R.H., Schraw, G.J., & Norby, M.M. (2011). Cognitive Psychology and Instruction (5th ed). Pearson.

- ↑ Schwartz, R. M. (2005). Literacy Learning of At-Risk First-Grade Students in the Reading Recovery Early Intervention. Journal Of Educational Psychology, 97(2), 257-267. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.97.2.257

- ↑ Bruning, R.H., Schraw, G.J., & Norby, M.M. (2011). Cognitive Psychology and Instruction (5th ed). Pearson.

- ↑ Bruning, R.H., Schraw, G.J., & Norby, M.M. (2011). Cognitive Psychology and Instruction (5th ed). Pearson.

- ↑ Bruning, R.H., Schraw, G.J., & Norby, M.M. (2011). Cognitive Psychology and Instruction (5th ed). Pearson.

- ↑ Bruning, R.H., Schraw, G.J., & Norby, M.M. (2011). Cognitive Psychology and Instruction (5th ed). Pearson.

- ↑ Ehri, L. C. (2005). Learning to read words: Theory, findings, and issues. Scientific Studies of Reading, 9(2), 167-188, doi: 10.1207/s1532799xssr0902_4

- ↑ Ehri, L. C. (2005). Learning to read words: Theory, findings, and issues. Scientific Studies of Reading, 9(2), 167-188, doi: 10.1207/s1532799xssr0902_4

- ↑ Bruning, R.H., Schraw, G.J., & Norby, M.M. (2011). Cognitive Psychology and Instruction (5th ed). Pearson.

- ↑ Bruning, R.H., Schraw, G.J., & Norby, M.M. (2011). Cognitive Psychology and Instruction (5th ed). Pearson.

- ↑ Ehri, L. C. (2005). Learning to read words: Theory, findings, and issues. Scientific Studies of Reading, 9(2), 167-188, doi: 10.1207/s1532799xssr0902_4

- ↑ Ehri, L. C. (2005). Learning to read words: Theory, findings, and issues. Scientific Studies of Reading, 9(2), 167-188, doi: 10.1207/s1532799xssr0902_4

- ↑ Ehri, L. C. (2005). Learning to read words: Theory, findings, and issues. Scientific Studies of Reading, 9(2), 167-188, doi: 10.1207/s1532799xssr0902_4

- ↑ Ehri, L. C. (2005). Learning to read words: Theory, findings, and issues. Scientific Studies of Reading, 9(2), 167-188, doi: 10.1207/s1532799xssr0902_4

- ↑ Ehri, L. C. (2005). Learning to read words: Theory, findings, and issues. Scientific Studies of Reading, 9(2), 167-188, doi: 10.1207/s1532799xssr0902_4

- ↑ Ehri, L. C. (2005). Learning to read words: Theory, findings, and issues. Scientific Studies of Reading, 9(2), 167-188, doi: 10.1207/s1532799xssr0902_4

- ↑ Ehri, L. C. (2005). Learning to read words: Theory, findings, and issues. Scientific Studies of Reading, 9(2), 167-188, doi: 10.1207/s1532799xssr0902_4

- ↑ Ehri, L. C. (2005). Learning to read words: Theory, findings, and issues. Scientific Studies of Reading, 9(2), 167-188, doi: 10.1207/s1532799xssr0902_4

- ↑ Bruning, R.H., Schraw, G.J., & Norby, M.M. (2011). Cognitive Psychology and Instruction (5th ed). Pearson.

- ↑ Bukowiecki, E. M. (2007). Teaching children how to read. Kappa Delta Pi Record, 43(2), 58-65. doi: 10.1080/00228958.2007.10516463

- ↑ Bruning, R.H., Schraw, G.J., & Norby, M.M. (2011). Cognitive Psychology and Instruction (5th ed). Pearson.

- ↑ Bukowiecki, E. M. (2007). Teaching children how to read. Kappa Delta Pi Record, 43(2), 58-65. doi: 10.1080/00228958.2007.10516463

- ↑ Bukowiecki, E. M. (2007). Teaching children how to read. Kappa Delta Pi Record, 43(2), 58-65. doi: 10.1080/00228958.2007.10516463

- ↑ Bukowiecki, E. M. (2007). Teaching children how to read. Kappa Delta Pi Record, 43(2), 58-65. doi: 10.1080/00228958.2007.10516463

- ↑ Bruning, R.H., Schraw, G.J., & Norby, M.M. (2011). Cognitive Psychology and Instruction (5th ed). Pearson.

- ↑ Bruning, R.H., Schraw, G.J., & Norby, M.M. (2011). Cognitive Psychology and Instruction (5th ed). Pearson.

- ↑ Bruning, R.H., Schraw, G.J., & Norby, M.M. (2011). Cognitive Psychology and Instruction (5th ed). Pearson.

- ↑ Vellutino, F.R. (1991). Introduction to three studies on reading acquisition: Convergent findings on theoretical foundations of code-oriented versus whole-language approaches to reading instruction. Journal of Educational Psychology, 83(4). 437-443. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.83.4.437

- ↑ Stein, M., Johnson, B., & Gutlohn, L., (1999). Analyzing Beginning Reading Programs: The Relationship Between Decoding Instruction and Text. Remedial and Special Education, 20(5), 275-287. doi:10.1177/074193259902000503

- ↑ Stein, M., Johnson, B., & Gutlohn, L., (1999). Analyzing Beginning Reading Programs: The Relationship Between Decoding Instruction and Text. Remedial and Special Education, 20(5), 275-287. doi:10.1177/074193259902000503

- ↑ Stein, M., Johnson, B., & Gutlohn, L., (1999). Analyzing Beginning Reading Programs: The Relationship Between Decoding Instruction and Text. Remedial and Special Education, 20(5), 275-287. doi:10.1177/074193259902000503

- ↑ Stein, M., Johnson, B., & Gutlohn, L., (1999). Analyzing Beginning Reading Programs: The Relationship Between Decoding Instruction and Text. Remedial and Special Education, 20(5), 275-287. doi:10.1177/074193259902000503

- ↑ Stein, M., Johnson, B., & Gutlohn, L., (1999). Analyzing Beginning Reading Programs: The Relationship Between Decoding Instruction and Text. Remedial and Special Education, 20(5), 275-287. doi:10.1177/074193259902000503

- ↑ Stein, M., Johnson, B., & Gutlohn, L., (1999). Analyzing Beginning Reading Programs: The Relationship Between Decoding Instruction and Text. Remedial and Special Education, 20(5), 275-287. doi:10.1177/074193259902000503

- ↑ Stein, M., Johnson, B., & Gutlohn, L., (1999). Analyzing Beginning Reading Programs: The Relationship Between Decoding Instruction and Text. Remedial and Special Education, 20(5), 275-287. doi:10.1177/074193259902000503

- ↑ Stein, M., Johnson, B., & Gutlohn, L., (1999). Analyzing Beginning Reading Programs: The Relationship Between Decoding Instruction and Text. Remedial and Special Education, 20(5), 275-287. doi:10.1177/074193259902000503

- ↑ Vellutino, F.R. (1991). Introduction to three studies on reading acquisition: Convergent findings on theoretical foundations of code-oriented versus whole-language approaches to reading instruction. Journal of Educational Psychology, 83(4). 437-443. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.83.4.437

- ↑ Bruning, R.H., Schraw, G.J., & Norby, M.M. (2011). Cognitive Psychology and Instruction (5th ed). Pearson.

- ↑ Maddox, K., & Feng, J. (2013). Whole Language Instruction vs. Phonics Instruction: Effects on Reading Fluency and Spelling Accuracy of First Grade Students. Retrieved from ERIC database. (ED545621)

- ↑ Ehri, L. C., Nunes, S. R., Willows, D. M., Schuster, B. V., Yaghoub-Zadeh, Z., & Shanahan, T.. (2001). Phonemic Awareness Instruction Helps Children Learn to Read: Evidence from the National Reading Panel's Meta-Analysis. Reading Research Quarterly, 36(3), 250–287. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/748111

- ↑ Ehri, L. C., Nunes, S. R., Willows, D. M., Schuster, B. V., Yaghoub-Zadeh, Z., & Shanahan, T.. (2001). Phonemic Awareness Instruction Helps Children Learn to Read: Evidence from the National Reading Panel's Meta-Analysis. Reading Research Quarterly, 36(3), 250–287. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/748111

- ↑ Castle, J.M., Riach, J., & Nicholson, T. (1994). Getting Off to a Better Start in Reading and Spelling: The Effects of Phonemic Awareness Instruction Within a Whole Language Program. Journal of Educational Psychology, 86(3), 350-359. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.86.3.350

- ↑ Ehri, L. C., Nunes, S. R., Willows, D. M., Schuster, B. V., Yaghoub-Zadeh, Z., & Shanahan, T.. (2001). Phonemic Awareness Instruction Helps Children Learn to Read: Evidence from the National Reading Panel's Meta-Analysis. Reading Research Quarterly, 36(3), 250–287. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/748111

- ↑ Ehri, L. C., Nunes, S. R., Willows, D. M., Schuster, B. V., Yaghoub-Zadeh, Z., & Shanahan, T.. (2001). Phonemic Awareness Instruction Helps Children Learn to Read: Evidence from the National Reading Panel's Meta-Analysis. Reading Research Quarterly, 36(3), 250–287. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/748111

- ↑ Ehri, L. C., Nunes, S. R., Willows, D. M., Schuster, B. V., Yaghoub-Zadeh, Z., & Shanahan, T.. (2001). Phonemic Awareness Instruction Helps Children Learn to Read: Evidence from the National Reading Panel's Meta-Analysis. Reading Research Quarterly, 36(3), 250–287. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/748111

- ↑ McCaslin, M. M.. (1989). Whole Language: Theory, Instruction, and Future Implementation. The Elementary School Journal, 90(2), 223–229. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org.proxy.lib.sfu.ca/stable/1002031

- ↑ Stone, T. J. (1993). Whole language reading processes from a Vygotskian perspective. Child & Youth Care Forum, 22(5), 361-373. doi:10.1007/BF00760945

- ↑ Stone, T. J. (1993). Whole-language reading processes from a Vygotskian perspective. Child & Youth Care Forum, 22(5), 361-373. doi:10.1007/BF00760945

- ↑ Stone, T. J. (1993). Whole-language reading processes from a Vygotskian perspective. Child & Youth Care Forum, 22(5), 361-373. doi:10.1007/BF00760945

- ↑ Vellutino, F.R. (1991). Introduction to three studies on reading acquisition: Convergent findings on theoretical foundations of code-oriented versus whole-language approaches to reading instruction. Journal of Educational Psychology, 83(4). 437-443. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.83.4.437

- ↑ Stone, T. J. (1993). Whole-language reading processes from a Vygotskian perspective. Child & Youth Care Forum, 22(5), 361-373. doi:10.1007/BF00760945

- ↑ Stone, T. J. (1993). Whole-language reading processes from a Vygotskian perspective. Child & Youth Care Forum, 22(5), 361-373. doi:10.1007/BF00760945

- ↑ McCaslin, M. M.. (1989). Whole Language: Theory, Instruction, and Future Implementation. The Elementary School Journal, 90(2), 223–229. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org.proxy.lib.sfu.ca/stable/1002031

- ↑ Stone, T. J. (1993). Whole-language reading processes from a Vygotskian perspective. Child & Youth Care Forum, 22(5), 361-373. doi:10.1007/BF00760945

- ↑ Stone, T. J. (1993). Whole-language reading processes from a Vygotskian perspective. Child & Youth Care Forum, 22(5), 361-373. doi:10.1007/BF00760945

- ↑ Stone, T. J. (1993). Whole-language reading processes from a Vygotskian perspective. Child & Youth Care Forum, 22(5), 361-373. doi:10.1007/BF00760945

- ↑ Stone, T. J. (1993). Whole-language reading processes from a Vygotskian perspective. Child & Youth Care Forum, 22(5), 361-373. doi:10.1007/BF00760945

- ↑ Stone, T. J. (1993). Whole-language reading processes from a Vygotskian perspective. Child & Youth Care Forum, 22(5), 361-373. doi:10.1007/BF00760945

- ↑ Stone, T. J. (1993). Whole-language reading processes from a Vygotskian perspective. Child & Youth Care Forum, 22(5), 361-373. doi:10.1007/BF00760945

- ↑ Krashen, S.D. (2002). Defending whole language: the limits of phonics instruction and the efficacy of whole language instruction. Reading Improvement, 39(1), 32-42.

- ↑ Manning, M., & Kamii, C. (2000). Whole Language vs. Isolated Phonics Instruction: A Longitudinal Study in Kindergarten With Reading and Writing Tasks, Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 15(1), 53-65. doi: 10.1080/02568540009594775

- ↑ Shuying, A. (2013). Schema Theory in Reading. Theory & Practice in Language Studies, 3(1), 130-134. doi:10.4304/tpls.3.1.130-134

- ↑ Shuying, A. (2013). Schema Theory in Reading. Theory & Practice in Language Studies, 3(1), 130-134. doi:10.4304/tpls.3.1.130-134

- ↑ Tracey, D.H., & Morrow, L.M. (2012). Lenses on Reading, Second Edition : An Introduction to Theories and Models. Guilford Press.

- ↑ Tracey, D.H., & Morrow, L.M. (2012). Lenses on Reading, Second Edition : An Introduction to Theories and Models. Guilford Press.

- ↑ Tracey, D.H., & Morrow, L.M. (2012). Lenses on Reading, Second Edition : An Introduction to Theories and Models. Guilford Press.

- ↑ Shuying, A. (2013). Schema Theory in Reading. Theory & Practice in Language Studies, 3(1), 130-134. doi:10.4304/tpls.3.1.130-134

- ↑ Tracey, D.H., & Morrow, L.M. (2012). Lenses on Reading, Second Edition : An Introduction to Theories and Models. Guilford Press.

- ↑ Shuying, A. (2013). Schema Theory in Reading. Theory & Practice in Language Studies, 3(1), 130-134. doi:10.4304/tpls.3.1.130-134

- ↑ Shuying, A. (2013). Schema Theory in Reading. Theory & Practice in Language Studies, 3(1), 130-134. doi:10.4304/tpls.3.1.130-134

- ↑ Shuying, A. (2013). Schema Theory in Reading. Theory & Practice in Language Studies, 3(1), 130-134. doi:10.4304/tpls.3.1.130-134

- ↑ Al-Faki, I., & Siddiek, A. G. (2013). The role of background knowledge in enhancing reading comprehension. World Journal of English Language, 3(4), 42-n/a. Retrieved from https://www.proquest.com/docview/1525981385

- ↑ Tracey, D.H., & ;Morrow, L.M. (2012). Lenses on Reading, Second Edition : An Introduction to Theories and Models. Guilford Press.

- ↑ Tracey, D.H., & ;Morrow, L.M. (2012). Lenses on Reading, Second Edition : An Introduction to Theories and Models. Guilford Press.

- ↑ Al-Faki, I., & Siddiek, A. G. (2013). The role of background knowledge in enhancing reading comprehension. World Journal of English Language, 3(4), 42-n/a. Retrieved from https://www.proquest.com/docview/1525981385

- ↑ Maghsoudi, Najmeh. (2012). The impact of schema activation on reading comprehension of cultural texts among Iranian EFL learners. Canadian Social Science, 8(5), 196-201. doi:10.3968/j.css.1923669720120805.3131

- ↑ Bruning, R.H., Schraw, G.J., & Norby, M.M. (2011). Cognitive Psychology and Instruction (5th ed). Pearson.

- ↑ Bruning, R.H., Schraw, G.J., & Norby, M.M. (2011). Cognitive Psychology and Instruction (5th ed). Pearson.

- ↑ Walsh, R. (2009). Word games: The importance of defining phonemic awareness for professional discourse. Australian Journal of Language & Literacy, 32(3), 211-225. Retrieved from http://web.a.ebscohost.com.proxy.lib.sfu.ca/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=e203b503-b43d-4f66-b2e9-2534fa1b2905%40sessionmgr4002&vid=13&hid=4104

- ↑ Walsh, R. (2009). Word games: The importance of defining phonemic awareness for professional discourse. Australian Journal of Language & Literacy, 32(3), 211-225. Retrieved from http://web.a.ebscohost.com.proxy.lib.sfu.ca/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=e203b503-b43d-4f66-b2e9-2534fa1b2905%40sessionmgr4002&vid=13&hid=4104

- ↑ Bruning, R.H., Schraw, G.J., & Norby, M.M. (2011). Cognitive Psychology and Instruction (5th ed). Pearson.

- ↑ Bruning, R.H., Schraw, G.J., & Norby, M.M. (2011). Cognitive Psychology and Instruction (5th ed). Pearson.

- ↑ Bruning, R.H., Schraw, G.J., & Norby, M.M. (2011). Cognitive Psychology and Instruction (5th ed). Pearson.

- ↑ Bukowiecki, E. M. (2007). Teaching children how to read. Kappa Delta Pi Record, 43(2), 58-65. doi: 10.1080/00228958.2007.10516463

- ↑ Bukowiecki, E. M. (2007). Teaching children how to read. Kappa Delta Pi Record, 43(2), 58-65. doi: 10.1080/00228958.2007.10516463

- ↑ Bruning, R.H., Schraw, G.J., & Norby, M.M. (2011). Cognitive Psychology and Instruction (5th ed). Pearson.

- ↑ Bruning, R.H., Schraw, G.J., & Norby, M.M. (2011). Cognitive Psychology and Instruction (5th ed). Pearson.

- ↑ Bruning, R.H., Schraw, G.J., & Norby, M.M. (2011). Cognitive Psychology and Instruction (5th ed). Pearson.

- ↑ Bruning, R.H., Schraw, G.J., & Norby, M.M. (2011). Cognitive Psychology and Instruction (5th ed). Pearson.

- ↑ Bruning, R.H., Schraw, G.J., & Norby, M.M. (2011). Cognitive Psychology and Instruction (5th ed). Pearson.