History of video games/Print version/Fourth Generation of Video Game Consoles

| This is the print version of History of video games You won't see this message or any elements not part of the book's content when you print or preview this page. |

- Fourth generation of video game consoles

Trends

[edit | edit source]Improved hardware

[edit | edit source]

During this generation pixel art in games becomes more much more advanced, often adopting the pointillism art style to the medium to great effect.[1][2] Sprite based 2D graphics were essentially a solved problem by this generation, which lead to companies to look for ways to differentiate their graphics.

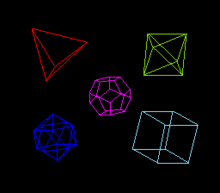

Game consoles also began using pre-rendered 3D Graphics and graphical techniques to give the impression of real 3D graphics running on hardware.[3] Games using simple real time 3D polygons became popular, though they often required enhancement chips to draw just a few hundred polygons a second.[4][5]

This generation audio improved drastically, with much more advanced audio systems.[6][7]

CD capable consoles

[edit | edit source]

This generation some companies attempted to release high end consoles with built in CD support, while others tried to launch CD add ons. Both strategies saw lukewarm adoption at best. CD-ROM technology was appealing because they could be used to add recorded video to games, recorded soundtracks, and other features. Furthermore, a high capacity CD-ROM was much cheaper to make ($2 for disk and packaging in 1993) compared to cartridges which held far less and cost far more.[8] As a result CD based games saved significant amounts of money for developers. The high lead times and cost of cartridges also lead to financial issues for companies who overproduced games they were unable to sell, further enhancing the appeal of CD-ROMs as a format to some developers.[9]

Yet CD-ROMs in consoles were not a fully ready technology this generation. Game Developers often used the extra space for enhanced graphics or audio, but often did not use the extra space to further gameplay in a way that could not be done on a cartridge. CD-ROM drives were still quite expensive, despite rapidly declining prices. They were also quite slow compared to cartridges, with long loading times compared to the near instant access allowed by a cartridge.

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ Irwin, Jon. "As SNES turns 25, devs discuss its 7 greatest graphics innovations". www.gamasutra.com. Retrieved 11 December 2020.

- ↑ "Pixel Art: Deconstructing Visuals of Videogames". 80.lv. 23 October 2015. Retrieved 11 December 2020.

- ↑ "Sega Genesis Games That Pushed The Limits of Graphics & Sound". RetroGaming with Racketboy. 3 July 2007. Retrieved 11 December 2020.

- ↑ "Games That Pushed The Limits of the Super Nintendo (SNES)". RetroGaming with Racketboy. 8 February 2011. Retrieved 11 December 2020.

- ↑ "Sega-16 – Sega's SVP Chip: The Road Not Taken?". Retrieved 11 December 2020.

- ↑ "MDFourier Project Seeks The Genesis Of SEGA 16-bit Sound". Hackaday. 2 August 2019. Retrieved 11 December 2020.

- ↑ "The Mysterious Legacy of the SNES Soundchip". Fatnick Industries. 19 August 2016. Retrieved 11 December 2020.

- ↑ "Sales of CD-ROMs Soared at the End of 1993 : Technology: Falling prices for computers, CD-ROM drives drove holiday software sales". Los Angeles Times. 29 March 1994. Retrieved 11 December 2020.

- ↑ McFerran, Damien (24 February 2022). "Retro: How A Remarkable Street Fighter Port Soured The Relationship Between Capcom And Nintendo". Nintendo Life. https://www.nintendolife.com/news/2022/02/retro-how-a-remarkable-street-fighter-port-soured-the-relationship-between-capcom-and-nintendo.

-

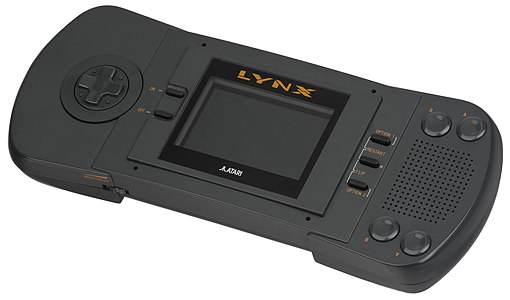

The Atari Lynx handheld game console.

-

The later Atari Lynx II revision.

History

[edit | edit source]

Development

[edit | edit source]The Lynx was originally developed by a company called Epyx in August 1987 as the Handy Project, with some members of the design team having previously worked on the Amiga series of computers.[1] The system later piqued the interest of Atari,[2] which acquired it and applied it's big cat naming scheme to the device.

Launch

[edit | edit source]The Atari Lynx was launched in fall of 1989.[3][4] The launch price of the Lynx was $179.99 US Dollars.[5][2] The Lynx received a positive reception, but struggled on the market due to issues Atari faced getting retailers to carry the console.[2]A redesigned Lynx was launched in 1991 with a reduced price of $99,[5] which made it much more price competitive with the Game Boy.

Legacy

[edit | edit source]Two to three million Lynx consoles were sold.[6][4] The discontinuation date of the Lynx is disputed, with discontinuation years given of 1992,[7] 1994,[8] or 1995.[5]

The Atari Lynx gained a dedicated fanbase, and saw multiple homebrew titles released as recently as 2019.[9]

Technology

[edit | edit source]

Compared to its rivals, the Lynx had a powerful mobile computer. The handheld is powered by the Mikey CPU, a version of the 8-bit WDC 65SC02 CPU clocked at 4 megahertz and the Suzy GPU clocked at 16 megahertz.[10] Games for the Lynx could leverage a powerful graphics system, supporting hundreds of sprites, and a software defined framerate.[1] The Lynx has 64 kilobytes of RAM.[11] Lynx game cartridges could store as much as 2 megabytes of ROM.[1]

The Lynx had a color display, which was backlit,[12] permitting handheld gaming in the dark. The screen can display 4,096 colors and has a resolution of 160 pixels by 102 pixels.[1] Both a color screen and night time visibility were not universal at the time, which was a significant advantage for the Lynx.

The superior features of the Lynx required a very high power draw, and so the handheld used 6 AA batteries,[11] a significant disadvantage compared to more efficient competitors such as the Game Boy. Battery life typically lasted under 4 hours,[7] though the system could be powered by an AC adapter when near an outlet.[1] At the time, most AA batteries were non rechargeable, making operating the console a significant expense. In contrast to other handhelds of the time which were typically constrained by processor power or their display, the power consumption of the Lynx its biggest technological Achilles' Heel.

The Atari Lynx has an ambidextrous design,[4] a fairly unique choice among handheld game consoles. This made the system equally suitable for left handed or right handed gamers, though labeling does appear designed for right hand use.

Retail games for the system were packaged in cardboard boxes.[5]

Notable games

[edit | edit source]Wikipedia has a list of Atari Lynx games.

Gallery

[edit | edit source]Atari Lynx I

[edit | edit source]Atari Lynx II

[edit | edit source]Accessories

[edit | edit source]Lynx I Internals

[edit | edit source]Lynx II Internals

[edit | edit source]Developers

[edit | edit source]-

R J Mical playing a Lynx, the system he co-designed.

-

Dave Needle, one of the co-designers of the Lynx.

External Resources

[edit | edit source]- iFixit - Atari Lynx page.

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ a b c d e "Lynx Creators - The Atari Times". web.archive.org. 16 September 2014. https://web.archive.org/web/20140916114505/http://ataritimes.com/index.php?ArticleIDX=370.

- ↑ a b c "Jack Tramiel and Family - Six Years with Atari". Day in Tech History. 17 October 2013. https://dayintechhistory.com/news/jack-tramiel-family-years-atari/.

- ↑ Parish, Jeremy (4 July 2014). "Too Powerful for Its Own Good, Atari's Lynx Remains a Favorite 25 Years Later" (in en). USgamer. https://www.usgamer.net/articles/too-good-for-its-day-ataris-lynx-remains-a-fan-favorite-25-years-later. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- ↑ a b c "Handheld video game console:Atari Lynx Handheld Console with Case - Atari, Inc". Google Arts & Culture. Retrieved 15 November 2020.

- ↑ a b c d "Collecting The Obscure: A Look At Atari's Failed Handheld Video Game System Antiques & Auction News". antiquesandauctionnews.net. Retrieved 18 January 2021.

- ↑ "History Lesson: The consoles that 'failed'". VGC. 28 December 2019. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- ↑ a b "Atari Lynx II (Rygar Box) - Game Console - Computing History". www.computinghistory.org.uk. Retrieved 18 January 2021.

- ↑ "Welcome to The Atari Times". www.ataritimes.com. Retrieved 18 January 2021.

- ↑ Kromin, Igor. "In 2019 we have eleven new games for the Atari Lynx | Atari Gamer" (in en). atarigamer.com. https://atarigamer.com/articles/in-2019-we-have-eleven-new-games-for-the-atari-lynx.

- ↑ "Atari Lynx". Wikipedia. 9 November 2020. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- ↑ a b "OLD-COMPUTERS.COM : The Museum". www.old-computers.com. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- ↑ "The Atari Lynx’s 30th birthday gift is a bunch of new games" (in en). Engadget. https://www.engadget.com/2019-08-30-atari-lynx-30-year-anniversary.html. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

-

Sketch of the Atari Panther

History

[edit | edit source]The design of the Atari Panther was influenced by the Konix Multisystem.

The Atari Panther was supposed to release in 1991, but was ultimately scraped in favor of development on the Atari Jaguar.[1][2] The decision to cancel the console was made just 6 months prior to launch.[3]

A development system for the Atari Panther was produced,[4] which shows significant investment from Atari in the concept.

Technology

[edit | edit source]The primary Panther CPU was a Motorola 68000 clocked at 16 megahertz.[1] The Panther also used a 32-bit graphics processor clocked at 32 megahertz.[4][1][5]

Audio was handled by an Ensoniq ES5505 OTIS sound processor clocked at 8 megahertz and with support for up to 32 channels of PCM audio.[6][7]

Gallery

[edit | edit source]-

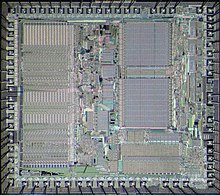

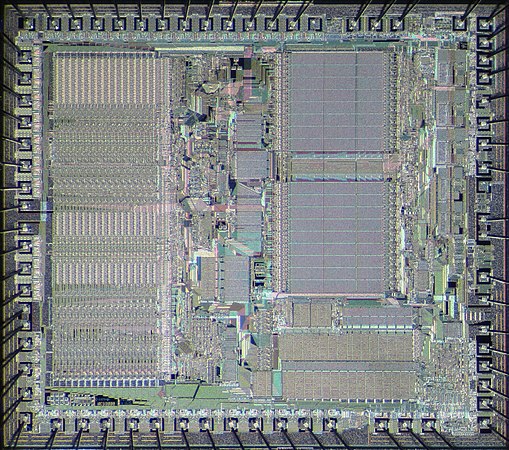

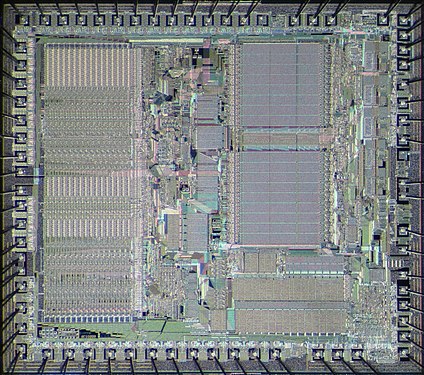

The die of a Motorola 68000.

-

An Ensoniq ES-5506, a similar chip to the ES5505.

External Resources

[edit | edit source]- Atari Museum - Panther page with design documents.

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ a b c "Atari Panther - Ultimate Console Database". ultimateconsoledatabase.com. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- ↑ "AEX - The most comprehensive exploration of Atari online". web.archive.org. 2 December 2003. https://web.archive.org/web/20031202031226/http://www.atari-explorer.com/jaguar-panther.html.

- ↑ "AEX - The most comprehensive exploration of Atari online". web.archive.org. 2 December 2003. https://web.archive.org/web/20031202031226/http://www.atari-explorer.com/jaguar-panther.html.

- ↑ a b "Atari Panther 32-Bit Game Console". www.atarimuseum.com. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- ↑ "Atari Panther: The Extinct Cat | AUSRETROGAMER" (in en-AU). 28 June 2017. https://ausretrogamer.com/atari-panther-the-extinct-cat/.

- ↑ Miazzo, Valentino (7 November 2018). "The Atari Panther - Part 2 - The hardware". Valentino Miazzo. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- ↑ Hawken, Kieren (9 May 2016). "10 Unreleased Video Game Consoles You Never Knew Existed" (in en). WhatCulture.com. https://whatculture.com/gaming/10-unreleased-video-game-consoles-you-never-knew-existed?page=9.

-

A Barcode Battler.

History

[edit | edit source]

The Barcode Battler was released by Epoch in 1991, and was very successful in Japan, but less successful in Europe.[1][2][3]

The system was an early example of a game that attempted to leverage real world data in gameplay, and is notable for doing so in an era before widespread internet access, accurate and cheap public GPS access, or other common systems used in contemporary games that leverage real world conditions.

Technology

[edit | edit source]Little reliable information exists for the technological specifications of the Barcode Battler.

The Barcode Battler is said to be powered by a N2A03 CPU clocked at 1 megahertz.[4]

The system supports a two player mode.[5]

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ Allen, Jennifer (10 July 2019). "Not even Mario and Zelda could make the Barcode Battler any good". Eurogamer. Retrieved 30 October 2020.

- ↑ "THE FORGOTTEN EPIC". The Game Scholar. 10 June 2020. Retrieved 30 October 2020.

- ↑ Shih, Gerry C. (25 June 2009). "Game Changer in Retailing, Bar Code Is 35 (Published 2009)". The New York Times. Retrieved 30 October 2020.

- ↑ "Barcode World (Jpn) - Jamma Play". www.jammaplay.com. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- ↑ "Epoch Barcode Battler [BINARIUM]". binarium.de. Retrieved 20 November 2020.

History

[edit | edit source]

The Capcom Power System Changer was essentially an attempt by Capcom to mimic the success of the NEO•GEO home console produced by SNK.[2]

The Capcom Power System Changer saw a limited Japanese release near the end of 1994, with a launch price of 39,800 yen.[2][3] The system was on the market for a short time, and was only supported until 1995.[3]

Technology

[edit | edit source]Compute

[edit | edit source]Games for the Capcom Power System Changer were based on CPS1 arcade boards, which are essentially self contained in cartridges.[3][4]

The Capcom Power System Changer itself only includes a processor based on the Motorola 68000 clocked at 10 megahertz and a Sony CXA1645 chip to handle converting JAMMA arcade standards into home friendly IO.[3][4]

Hardware

[edit | edit source]The system uses Super Famicom compatible controllers.[3]

Games

[edit | edit source]11 games were released for the Capcom Power System Changer.[3][5]

Gallery

[edit | edit source]-

The CPU used on the CPS1 arcade board.

-

A Motorola 6800 CPU die, similar to what would have been used in the Capcom Power System Changer.

External Resources

[edit | edit source]- Video Game Console Library - Capcom Power System Changer page.

- Video Game Kraken - Capcom Power System Changer page.

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ "CAPCOM History". www.capcom.co.jp. Retrieved 20 January 2021.

- ↑ a b "CPS Changer by Capcom – The Video Game Kraken". Retrieved 20 January 2021.

- ↑ a b c d e f "Feature: Say Hello To The CPS Changer, Capcom's First And Only Attempt At A Home Console". Nintendo Life. 25 February 2015. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- ↑ a b "Capcom CPS Changer". Video Game Console Library. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- ↑ "The Capcom Power System Changer: the next-gen of yesteryear". Retrieved 25 November 2020.

-

A Philips CD-i 220 with a controller attached.

-

A Phillips CD-i 400 with a controller attached.

History

[edit | edit source]

Pre-launch

[edit | edit source]As early as December 1987 the CD-i and the ambitious concept behind it was highly anticipated by some media outlets.[2]

Launch

[edit | edit source]The CD-i was launched in 1991.[3] The platform was not marketed well early on, though a 1991 partnership with Nintendo on developing a CD-based add-on for the Super Nintendo gave Phillips the right to produce several games based on existing Nintendo game series.[4]

From October 25th, 1995 to sometime around 2000, the CD-i could access an online service known as CD-Online.[4][5]

Legacy

[edit | edit source]System

[edit | edit source]Phillips stopped active development of the CD-i in 1996 and the system was discontinued in 1998, with between 570,000 and one million CD-i consoles sold worldwide.[3][4][6]

Games

[edit | edit source]

| “ | I don't know that those really fit in the Zelda franchise. | ” |

—Eiji Aonuma - 2013, MTV Interview regarding the Hyrule Historia.[7] | ||

Mention of the CD-i Zelda games would often be omitted from official Nintendo retrospectives.[8]

Technology

[edit | edit source]Computation

[edit | edit source]The CD-i was powered by a Motorola 68000 processor clocked at 15.5 MHz.[9][10] This was a very common processor for this generation of consoles.

The CD-i had one megabyte of RAM.[10] A digital video add-on cartridge added an additional 1.5 megabytes of RAM, as well as allowing the CD-i to decode MPEG-1 video.[4] Finally the CD-i had eight kilobytes of persistent storage based on RAM, powered by a lithium battery, which is prone to failure from age.[4]

At the time of release, the CD-i was seen as a low performance system with a design that was relatively easy to develop for.[9]

Hardware

[edit | edit source]The CD-i could read CD-ROM Green Book disks at 170 kilobits per second.[4]

The CD-i runs a custom version of Microware OS9, a real-time operating system called CD-RTOS.[9][11] The CD-i supported the CD-Online service, which required the use of an adapter cable, software disk, and a 14.4K dial-up modem.[5]

Notable games

[edit | edit source]1993

[edit | edit source]Zelda: The Wand of Gamelon

[edit | edit source]An early counterpart game to Link: The Faces of Evil with a female protagonist, departing from Zelda-series norms to feature the titular Princess Zelda as the protagonist.

Read more about Zelda: The Wand of Gamelon on Wikipedia.

Link: The Faces of Evil

[edit | edit source]A counterpart game to Zelda: The Wand of Gamelon.

The game attracted widespread internet notoriety again in early 2021, when an artist redrew the character Morshu using hyper realistic 3D Graphic techniques.[12][13][14]

Read more about Link: The Faces of Evil on Wikipedia.

1994

[edit | edit source]Zelda's Adventure

[edit | edit source]The lesser known of the three Zelda games for the CD-i, it features live action cutscenes, perhaps the only Zelda-series game to do so. It also featured the titular princess as the protagonist, another departure from the typical Zelda-series formula at the time.

Read more about Zelda's Adventure on Wikipedia.

Hotel Mario

[edit | edit source]Read more about Hotel Mario on Wikipedia.

1996

[edit | edit source]RAM Raid

[edit | edit source]A notable early online FPS.

1997

[edit | edit source]Brain Dead 13

[edit | edit source]Read more about Brain Dead 13 on Wikipedia.

Burger King CD-i

[edit | edit source]Early game-based training software.

2022

[edit | edit source]Nobelia

[edit | edit source]Commercial homebrew game and platform exclusive released long after the CD-i was discontinued from the market.[15]

Cancelled

[edit | edit source]Super Mario's Wacky Worlds

[edit | edit source]A planned sequel to the SNES game Super Mario World.[16] An incomplete version of the game eventually surfaced.[17]

Read more about Super Mario's Wacky Worlds on Wikipedia.

Mario Takes America

[edit | edit source]Another canceled Mario game for the CD-i, with this title using a combination of real life photography and filming and overlaid 2D artwork.[18]

Gallery

[edit | edit source]Consoles

[edit | edit source]-

CDi 220 from the front right.

-

CDi 220 from the back left.

-

CDi 220 from the back right.

-

CDI 910 front with controller attached. The controller has its direction stick unscrewed.

-

CDI 910 rear showing IO and expansion socket. This console was made in Belgium.

Controllers

[edit | edit source]-

Paddle Controller

-

Gamepad

-

Roller Controller

-

The CDi Mouse

Remote controls

[edit | edit source]References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ "Philips CD-i 490 - Game Console - Computing History". www.computinghistory.org.uk. Retrieved 2020-12-12.

- ↑ "Vers un nouveau support : le CD-I Les charmes discrets de l'interactivité" (in fr). Le Monde. 1987-12-17. https://www.lemonde.fr/archives/article/1987/12/17/vers-un-nouveau-support-le-cd-i-les-charmes-discrets-de-l-interactivite_4079184_1819218.html.

- ↑ a b Damien, McFerran (2017-03-09). "6 games console flops that gave gaming a bad name" (in en). TechRadar. https://www.techradar.com/news/6-games-console-flops-that-gave-gaming-a-bad-name. Retrieved 2020-10-25.

- ↑ a b c d e f "Hardware Classics: Uncovering The Tragic Tale Of The Philips CD-i". Nintendo Life. 2018-07-23. Retrieved 2020-11-17.

- ↑ a b "Philips CD-Online - The Service Time Forgot (guest article by RetroDetect about the timeline of CD-i's Internet Kit and the CD-Online service)". Retrieved 2020-11-17.

- ↑ "The 10 Worst-Selling Consoles of All Time (page 2 of 2)". GamePro.com. 2007-11-03. Archived from the original on 2007-11-03. Retrieved 2020-11-17.

- ↑ a b "Eiji Aonuma Addresses Those Horrible ‘Zelda’ CD-i Games". web.archive.org. 3 December 2013. https://web.archive.org/web/20131203072003/http://multiplayerblog.mtv.com/2013/09/19/eiji-aonuma-addresses-those-horrible-zelda-cd-i-games/.

- ↑ McFerran, Damien (20 September 2013). "Surprise! Aonuma Doesn't Consider The CD-i Zelda Games To Be Canon, Either". Nintendo Life. https://www.nintendolife.com/news/2013/09/surprise_aonuma_doesnt_consider_the_cd_i_zelda_games_to_be_canon_either.

- ↑ a b c "Philips CD-i". Retro Gamer. Retrieved 2020-11-17.

- ↑ a b "Video Game Console Library CDi". Video Game Console Library. Retrieved 2020-11-18.

- ↑ "First Steps in OS-9 on Philips CDI605T". Retrostuff. 2019-07-21. Retrieved 2020-11-17.

- ↑ "Random: Morshu From Link: The Faces of Evil Has Been Turned Into A 3D Animation". Nintendo Life. 2021-01-24. https://www.nintendolife.com/news/2021/01/random_morshu_from_link_the_faces_of_evil_has_been_turned_into_a_3d_animation.

- ↑ "Forgotten Zelda NPC Is Horrifying In Full 3D". ScreenRant. 2021-01-26. https://screenrant.com/forgotten-zelda-npc-full-3d-cdi-horrifying/.

- ↑ "Zelda Fan Creates 3D Render of Morshu From Link: The Faces of Evil". Game Rant. 2021-01-25. https://gamerant.com/zelda-fan-creates-3d-render-morshu-link-faces-of-evil/.

- ↑ Whitehead, Thomas (16 March 2022). "Random: 'Zelda Meets Bomberman' In Nobelia, A New Philips CD-i Game". Nintendo Life. https://www.nintendolife.com/news/2022/03/random-zelda-meets-bomberman-in-nobelia-a-new-philips-cd-i-game.

- ↑ Zell-Breier, Sam (2021-01-07). "The Embarrassing Mario Games That Ended Up On Philips CD-I". Looper.com. https://www.looper.com/308532/the-embarrassing-mario-games-that-ended-up-on-philips-cd-i/.

- ↑ "Some Mario Games Just Can't Be Played Properly Anymore". Nintendo Life. 2018-05-19. https://www.nintendolife.com/news/2018/05/feature_some_mario_games_just_cant_be_played_properly_anymore.

- ↑ "The Cancelled Mario Game that was Taken Away by a Bank in Canada". Unseen64: Beta, Cancelled & Unseen Videogames!. 15 September 2014. https://www.unseen64.net/2014/09/15/mario-takes-america-cdi-cancelled/.

| Parts of this page are based on materials from: Wikipedia: the free encyclopedia. |

-

A CDTV unit with controller, keyboard, and mouse.

History

[edit | edit source]

The system was announced in Summer of 1990.[1] At CES 1990 the Commodore 64 Games System overshadowed the Commodore CDTV at the Commodore booth.[2]

The CDTV was launched in 1991[3].

The system was discontinued in 1993.[3] Sales for the CDTV were as low as 30,000 units,[3] with the highest sales figures given is still under 60,000 units.[4] Despite poor sales of the CDTV, Commodore would try again with a similar concept in the Amiga CD32.

Technology

[edit | edit source]The CDTV is based on a Amiga 500 computer equipped with 1 megabyte of RAM.[5]

Gallery

[edit | edit source]Notes

[edit | edit source]CDTV stands for "Commodore Dynamic Total Vision",[6][7] rather then the commonly assumed "Compact Disk TeleVision".

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ Olafson, Peter. "Definitive CDTV Retrospective". www.amigareport.com. https://www.amigareport.com/ar501/feature2.html.

- ↑ "What games were released for the C64 GS?" (in en). Commodore Format Archive. 2021-01-11. https://commodoreformatarchive.com/new-what-games-were-released-for-the-commodore-64-gs/.

- ↑ a b c "Commodore CDTV (1991 - 1993)". Museum of Obsolete Media. 6 May 2020. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- ↑ Civera, David (January 11, 2013). "21 Consoles And Handhelds That Crashed And Burned" (in en). Tom's Hardware. https://www.tomshardware.com/picturestory/611-console-handheld-fail.html.

- ↑ Blanchard, Jonn (29 December 2017). "Commodore CDTV". Re-enthused: world of retro. Retrieved 30 October 2020.

- ↑ "Commodore CDTV". oldcomputers.net. Retrieved 20 September 2021.

- ↑ "The Amiga Museum » CDTV". Retrieved 20 September 2021.

-

A Gamate console and game cards.

History

[edit | edit source]

Not to be confused with the earlier, but unrelated VTech 3D Gamate.

Released by Bit Corp in 1990, Bit Corp folded in 1992 but UMC would continue production until around 1993, with the Gamate's biggest market only being a modest presence in Italy.[1][2]

The Gamate was a failure in the market and it is speculated that the Gamate sold worse then the Watara Supervision.[3]

Technology

[edit | edit source]The Gamate uses a clone of the 8-bit MOS 6502 processor, either a UMC UA6588F or an NCR 81489.[4][5]

The Gamate probably has 16 kilobytes of RAM.[4]

The monochrome Gamate screen tends to ghost badly.[6]

Notable games

[edit | edit source]About 70 games were released for the system.[6]

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ Life, Nintendo (13 February 2014). "Feature: Meet The Gamate, The Handheld Which Tried To Take On The Game Boy And Failed". Nintendo Life. Retrieved 30 October 2020.

- ↑ Life, Nintendo (30 January 2016). "Hardware Classics: Bit Corp Gamate". Nintendo Life. Retrieved 30 October 2020.

- ↑ "Gamate: Bit Corporation". fuji.drillspirits.net. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- ↑ a b "Gamate: Hardware". fuji.drillspirits.net. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- ↑ "Gamate". Wikipedia. 16 August 2020. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- ↑ a b "Gamate". Obsolete worlds. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

-

A GameBoy at the Nintendo World Store.

History

[edit | edit source]Development

[edit | edit source]Nintendo had previously made dedicated handheld consoles such as the Game & Watch series consoles as well as the Nintendo Computer Mah-Jong Yakuman, however the Game Boy would be their first handheld to play interchangeable cartridges

Launch

[edit | edit source]The GameBoy was released in 1989 on April 21st in Japan and July 31st in the United States of America.[1]

Project Atlantis

[edit | edit source]Project Atlantis was a canceled Game Boy successor that used a 32 bit ARM 7 CPU that was in development by 1995.[2] The system was canceled due to it's enormous size, high expense, and poor performance.[2][3]

GameBoy Color

[edit | edit source]The GameBoy Color was released on November 18th, 1998.[1]

A touch screen adapter for the GameBoy Color was developed, but never released.[3]

Third party support for the system was large, with even a sewing machine supporting control over Game Boy link cable.[4]

In 2001 the Mobile System GB released in Japan for 5800 yen.[5] Though it allowed a Game Boy to connect to cell phones to access the internet on the go, it had a number of fees associated with using it, and sold under 100,000 units.[5]

Legacy

[edit | edit source]In 2003 the original GameBoy was discontinued,[6] having been succeeded by the Game Boy Advance line of consoles. The GameBoy and the GameBoy Color sold 118.69 million units collectively.[7][8]

GameBoy emulation has proven to be a fairly common topic in programming education.[9] [10] In 2020 researchers made the Engage an unofficial ultra low power GameBoy hardware clone which required no battery power to operate, instead being powered by solar energy and energy captured from button presses.[11]

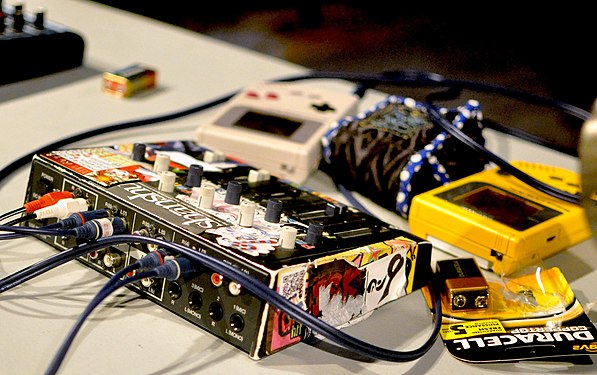

The Game Boy became would later become a popular musical instrument for Chiptune music creation.[12][13]

Technology

[edit | edit source]In terms of technical capabilities, the Game Boy is often thought of as a portable Nintendo Entertainment System, though the internal architectures of these systems are radically different.

Original GameBoy

[edit | edit source]Compute

[edit | edit source]

The GameBoy uses a 8 bit Z80 CPU clocked at 4.194304 megahertz.[14][7][15]

The GameBoy has eight kilobytes of RAM and eight kilobytes of VRAM.[16]

Display

[edit | edit source]

The GameBoy has a 160 by 144 resolution LCD.[14] The dot matrix display could display four shades from green to grey, making it monochrome.[17]

Audio

[edit | edit source]The GameBoy has four channels of stereo sound.[7] The system only had a single built in speaker, restricting the system to monophonic audio by default and requiring headphones for full stereo audio output.[18]

Networking

[edit | edit source]The GameBoy has a link cable port.[14]

Power

[edit | edit source]The original GameBoy uses four AA batteries and draws 70 to 80 mAh an hour, lasting about 30 hours.[14]

GameBoy Color

[edit | edit source]The GameBoy color possessed significantly increased specs compared to the original monochrome models.

Compute

[edit | edit source]An 8-bit Z80 based CPU clocked at 8.388 megahertz powers the GameBoy Color.[14][15]

The GameBoy color has 32 Kilobytes of RAM.[14]

Display

[edit | edit source]The GameBoy color uses a color TFT LCD, with a resolution of 160 by 144 pixels, 32,000 colors displayable, and 56 simultaneous colors.[14]

Networking

[edit | edit source]A link cable port and inferred port are present.[14]

Power

[edit | edit source]The GameBoy color takes two AA batteries, and draws 70 to 80 mAh an hour, lasting for about 10 hours of runtime.[14]

Accessories

[edit | edit source]Some Suzuki and Aprillia motorcycles are designed to hook up to a Game Boy Color through a special cable and cartridge combination for diagnostics access.[19]

A work oriented accessory, the WorkBoy keyboard and cartridge combo was planned but not released.[20]

Notable Games

[edit | edit source]1989

[edit | edit source]

Tetris

[edit | edit source]The rights to Tetris proved to be a contentious issue between those who claimed rights and the Soviet government.[21]

Read more about Tetris on Wikipedia.

1991

[edit | edit source]1992

[edit | edit source]- Super Mario Land 2: 6 Golden Coins

- Kirby's Dream Land - The first Kirby game

- X - Early 3D Game on the GameBoy

1993

[edit | edit source]1994

[edit | edit source]1996

[edit | edit source]Pokemon Red and Blue

[edit | edit source]The first Pokemon games were inspired by series creator Satoshi Tajiri's experience catching bugs as a youth in Machida, Japan.[22][23]

At the last minute an additional Pokemon was added by the development team to make the total number of monsters catchable 151.[24] This addition caused a number of urban legends and myths regarding an in game truck.[24]

The spooky ambiance of the in game location Lavender Town sparked a number of urban legends and myths.[25]

-

A short documentary on Satoshi Tajiri and the creation of Pokemon by YouTube channel Video Game Story Time.

-

The Kanto region in pokemon loosely corresponds to the Kantō region in Japan.

-

A natural area in the now urbanized Machida, Japan. Natural areas similar to this served as the inspiration for the Pokemon games.

1997

[edit | edit source]1998

[edit | edit source]1999

[edit | edit source]Mario Golf

[edit | edit source]Mario Golf for the GBA mixed golf mechanics with a simple RPG, sparking a small genre of golf RPGs.[26]

Read more about Mario Golf on Wikipedia.

Pokémon Gold and Silver

[edit | edit source]Then HAL Laboratory President Satoru Iwata was brought on to help with making compression tools for game graphics.[27]

Read more about Pokémon Gold and Silver on Wikipedia.

-

A short documentary on Satoru Iwata's involvement in Pokemon by YouTube channel Video Game Story Time.

-

The Hōryū-ji. In game locations were inspired by the Kansai region in Japan.[28]

-

Pokemon Silver cartridge board. Note the coin cell battery.

2000

[edit | edit source]Metal Gear Solid Ghost Babel

[edit | edit source]The track "Ascent" is a particularly impressive piece of chiptune. Read more about Metal Gear Solid Ghost Babel on Wikipedia.

2001

[edit | edit source]2002

[edit | edit source]Special edition GameBoys

[edit | edit source]- Yellow Tommy Hilfiger Game Boy Color.[29]

Gallery

[edit | edit source]Original GameBoy

[edit | edit source]GameBoy Pocket

[edit | edit source]GameBoy Light

[edit | edit source]GameBoy Color

[edit | edit source]GameBoy Accessories

[edit | edit source]Game Genie

[edit | edit source]-

A Game Genie for the Game Boy

-

A Game Genie attached to a Game Boy.

GameBoy Internals

[edit | edit source]Color palettes

[edit | edit source]-

Simulated colors of the original Game Boy.

-

Simulated colors of the Game Boy Pocket.

-

Simulated colors of the Game Boy Color.

-

One of the color palettes used by the Game Boy Color when using an monochrome original Game Boy cartridges.

-

One of the color palettes used by the Game Boy Color when using an monochrome original Game Boy cartridges.

-

One of the color palettes used by the Game Boy Color when using an monochrome original Game Boy cartridges.

-

One of the color palettes used by the Game Boy Color when using an monochrome original Game Boy cartridges.

-

One of the color palettes used by the Game Boy Color when using an monochrome original Game Boy cartridges.

-

One of the color palettes used by the Game Boy Color when using an monochrome original Game Boy cartridges.

-

One of the color palettes used by the Game Boy Color when using an monochrome original Game Boy cartridges.

-

One of the color palettes used by the Game Boy Color when using an monochrome original Game Boy cartridges.

-

One of the color palettes used by the Game Boy Color when using an monochrome original Game Boy cartridges.

-

One of the color palettes used by the Game Boy Color when using an monochrome original Game Boy cartridges.

-

One of the color palettes used by the Game Boy Color when using an monochrome original Game Boy cartridges.

-

One of the color palettes used by the Game Boy Color when using an monochrome original Game Boy cartridges.

Marketing

[edit | edit source]-

Game Boy logotype.

-

Game Boy Pocket logotype.

-

Game Boy Light logotype.

-

Game Boy Color logotype.

Other

[edit | edit source]-

A GameBoy perpetually playing Tetris at the Nintendo World Store, having survived bombing during the Gulf War.

-

A Japanese Warranty included with a Game Boy.

-

Prototype Lemmings cartridge

-

Then first lady Hillary Clinton, plays a GameBoy on a flight in 1993.

-

The audio characteristics of the Game Boy would later be widely used by the Chiptune community, shown here.

-

The Ultimate Game Boy talk at CCC.

External Resources

[edit | edit source]Archived web materials

[edit | edit source]References

[edit | edit source]| Parts of this page are based on materials from: Wikipedia: the free encyclopedia. |

- ↑ a b "25 years of the Game Boy: A timeline of the systems, accessories, and games". VentureBeat. 21 April 2014. https://venturebeat.com/2014/04/21/25-years-of-the-game-boy-a-timeline-of-the-systems-accessories-and-games/. Retrieved 23 October 2020.

- ↑ a b "GDC: Nintendo's Unreleased Portable Prototypes" (in en-us). Wired. https://www.wired.com/2009/03/gdc-nintendos-u/. Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- ↑ a b "A look into Nintendo's unreleased Game Boy successor" (in en). Nintendo Everything. 17 April 2016. https://nintendoeverything.com/a-look-into-nintendos-unreleased-game-boy-successor/. Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- ↑ "There Really Was A Sewing Machine Controlled By A Game Boy". Hackaday. 12 March 2020. https://hackaday.com/2020/03/11/there-really-was-a-sewing-machine-controlled-by-a-game-boy/. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- ↑ a b "That Time Nintendo Took the Game Boy (and Pokémon) Online" (in en-us). Kotaku. https://kotaku.com/that-time-nintendo-took-the-game-boy-and-pokemon-onli-1836423946. Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- ↑ Sun, Leo (30 April 2014). "Nintendo's Game Boy Turns 25 -- A Look Back at the Business of 'Withered Technology'". The Motley Fool. Retrieved 11 December 2020.

- ↑ a b c "Game Boy". Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- ↑ "IR Information : Sales Data - Dedicated Video Game Sales Units". Nintendo Co., Ltd. Retrieved 14 November 2020.

- ↑ "Why did I spend 1.5 months creating a Gameboy emulator? · tomek's blog". blog.rekawek.eu. Retrieved 11 December 2020.

- ↑ "Introduction - DMG-01: How to Emulate a Game Boy". blog.ryanlevick.com. Retrieved 11 December 2020.

- ↑ "The first battery-free Game Boy wants to power a gaming revolution". CNET. Retrieved 11 December 2020.

- ↑ "Chiptunes: Making Music with a Nintendo Game Boy The Library". library.berklee.edu. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ↑ "Make Chiptunes with a Gameboy | Open Music Initiative". omi.yale.edu. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i "Technical data". Nintendo of Europe GmbH. Retrieved 23 October 2020.

- ↑ a b "Everything You Always Wanted To Know About GAMEBOY". Retrieved 13 December 2020.

- ↑ "Game Boy Teardown". iFixit. 21 April 2019. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ↑ "Thirty Years Ago, Game Boy Changed the Way America Played Video Games". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 23 October 2020.

- ↑ "What is the meaning of the 'dot matrix with stereo sound' that is written on the Game Boy game console? - Quora". www.quora.com. https://www.quora.com/What-is-the-meaning-of-the-dot-matrix-with-stereo-sound-that-is-written-on-the-Game-Boy-game-console.

- ↑ "The GameBoy Motorcycle Accessory - What?". Retrieved 29 November 2020.

- ↑ "Lost Gameboy Peripheral WorkBoy Found After 28 Years" (in en). TechRaptor. https://techraptor.net/gaming/news/lost-gameboy-peripheral-workboy-found-after-28-years.

- ↑ "Tetris: how we made the addictive computer game" (in en). the Guardian. 2 June 2014. https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2014/jun/02/how-we-made-tetris.

- ↑ Lopez, German (13 July 2016). "Pokémon Go’s surprising roots: bug catching" (in en). Vox. https://www.vox.com/2016/7/13/12172826/pokemon-go-android-ios-bug-catching.

- ↑ "The Origins Of Pokémon". Kotaku. Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- ↑ a b "That Time Some Players Thought Mew Was Under A Truck In Pokémon" (in en-us). Kotaku. https://kotaku.com/that-time-some-players-thought-mew-was-under-a-truck-in-1792716938. Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- ↑ "Pokémon's Creepy Lavender Town Myth, Explained". Kotaku. Retrieved 30 October 2020.

- ↑ "Here's the launch trailer for Golf Story on Switch, the Game Boy Color Mario Golf follow-up we've wanted for 18 years". VG247. 28 September 2017. Retrieved 30 October 2020.

- ↑ "Iwata Asks". iwataasks.nintendo.com. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- ↑ Famularo, Jessica. "Pokemon's Ties to the Real World". Inverse. Retrieved 13 December 2020.

- ↑ "Looking Back At Some Of The Weirder Limited Edition Consoles" (in en-us). Kotaku. https://kotaku.com/looking-back-at-some-of-the-weirdest-limited-edition-co-1818480546.

-

The Sega Game Gear handheld.

History

[edit | edit source]

Development

[edit | edit source]While in development the Game Gear was known as Project Mercury.[1]

The Game Gear was made domestically in Japan.[2]

Launch

[edit | edit source]The Game Gear was launched in October of 1990 costing 19,800 yen.[2][1]

Discontinuation

[edit | edit source]Sega discontinued the Game Gear in 1997,[1] with 11 million consoles sold.[3] During the 30th anniversary of the system in 2020, Sega produced the Game Gear Micro a miniature reproduction of the Game Gear.

Technology

[edit | edit source]The internal architecture of the Game Gear is very similar to Sega's earlier home console, the Master System.[1][4]

Compute

[edit | edit source]The Game Gear uses an 8-bit Zilog Z80 based processor clocked at 3.58 megahertz.[5][4]

The Game Gear has eight kilobytes of RAM, and 16 kilobytes of video RAM.[4][6]

Hardware

[edit | edit source]The Game Gear has a 3.2 inch color screen with a resolution of 160 pixels by 144 pixels.[4][5]

The Game Gear uses a Texas Instruments SN76489 chip for sound.[4]

The Game Gear required the use of 6 AA batteries.[1]

Notable games

[edit | edit source]1991

[edit | edit source]- Eternal Legend

- Factory Panic

- Ax Battler: A Legend of Golden Axe

- House of Tarot

- Ninja Gaiden

- Head Buster

- Popils

1992

[edit | edit source]1993

[edit | edit source]1994

[edit | edit source]- Fred Couples Golf

- Coca-Cola Kid

- Megami Tensei Gaiden: Last Bible

- Poker Face Paul

- Popeye: Beach Volleyball

- X-Men

- X-Men: Gamesmaster's Legacy

1995

[edit | edit source]1996

[edit | edit source]Special Edition Game Gear Consoles

[edit | edit source]- Enjoy Coca-Cola Game Gear[7]

Gallery

[edit | edit source]Console

[edit | edit source]Internals

[edit | edit source]References

[edit | edit source]| Parts of this page are based on materials from: Wikipedia: the free encyclopedia. |

- ↑ a b c d e Life, Nintendo (3 June 2020). "Hardware Classics: Sega Game Gear - The System Which Spawned The Game Gear Micro". Nintendo Life. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- ↑ a b "HISTORY SEGA 60th Anniversary". SEGA 60th Anniversary site. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- ↑ "I'll Never Love a Console Like I Loved the SEGA Game Gear". www.vice.com. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ↑ a b c d e "Z80 Assembly programming for the Sega Master System and the Game Gear!". www.chibiakumas.com. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- ↑ a b "Sega Game Gear System Info". www.vgmuseum.com. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- ↑ "Sega's Game Gear turns 30". Young Post. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- ↑ Machkovech, Sam (30 April 2022). "Tasting Coca-Cola’s first “gamer” flavor—and the history of game-and-soda tie-ins" (in en-us). Ars Technica. https://arstechnica.com/gaming/2022/04/coca-colas-first-gamer-flavor-and-the-history-of-game-and-soda-tie-ins/.

History

[edit | edit source]The Hartung Game Master was a handheld game console that was released in 1990.[1] The system saw release in a number of western European countries, as well as Hong Kong.[2]

Technology

[edit | edit source]The Hartung Game Master uses an NEC upd7810 CPU.[3][4]

The Game Master has a monochrome LCD with a resolution of 64 by 64 pixels.[5][1]

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ a b Life, Nintendo (17 April 2019). "Feature: The Handheld Rivals Which Tried And Failed To Beat The Game Boy". Nintendo Life. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- ↑ "Game Master (console)". Wikipedia. 28 February 2021. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ↑ "About - Hartung Game Master - Games Database". www.gamesdatabase.org. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- ↑ "Gallery of Portable Gaming Systems". Video Game Console Library. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- ↑ "Game Master by Hartung – The Video Game Kraken". Retrieved 4 November 2020.

History

[edit | edit source]Original Picno

[edit | edit source]The first Konami Picno educational console was released in Japan in 1992 for ¥29,800 yen.[1][2]

Picno 2

[edit | edit source]The Picno 2 was launched in 1993 for ¥15,800 yen as a much cheaper followup console.[3]

Legacy

[edit | edit source]The Picno was discontinued around 1994.[2]

Technology

[edit | edit source]The Konami Picno uses a HD6435328F, a HN62334BP, a HM538121JP, a M514256B, and a custom chip.[4]

The Picno uses a touchpad built into the system for most of it's input.[5]

Notable games

[edit | edit source]A small number of educational titles and simple games were released for the Konami Picno.[6]

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ "ピクノ". Wikipedia (in Japanese). 25 May 2020. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- ↑ a b "Picno by Konami – The Video Game Kraken". Retrieved 27 November 2020.

- ↑ "Picno2 by Konami – The Video Game Kraken". Retrieved 27 November 2020.

- ↑ "Dumping Blog: Pico or Picno or is it a new console?". Dumping Blog. 7 November 2017. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- ↑ "The Lost History of The KONAMI Picno System - Rare Console History". Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- ↑ "mamedev/mame". GitHub. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

History

[edit | edit source]Development

[edit | edit source]The canceled system was planned for a August 1989 release at a cost 200 British pounds.[1] Funding issues caused the system to be shuttered shortly afterwards.[1]

A new version of the system focused on using only CDs in conjunction with a 32 bit processor clocked at 30 megahertz was announced in 1993.[2]

Legacy

[edit | edit source]Ultimately the controller would see a release by a different company as a PC game controller.[1]

The design of the Konnix Multisystem would later influence the Atari Panther, and from that the Atari Jaguar.[3]

Technology

[edit | edit source]Compute

[edit | edit source]The Konix Multisystem was powered by an 16-bit Intel 8086 processor clocked at 6 megahertz.[4][5] The system also had a 12 megahertz custom co-processor.[4][5]

The system started with 128 kilobytes of RAM, but later had 256 kilobytes of RAM which could be expanded to a total of 768 kilobytes of RAM with a proposed 512 kilobyte add on.[6][4]

Hardware

[edit | edit source]The system used special 880 kilobyte capacity 3.5 inch floppy disks.[4]

A morphing controller was planned.[1]

A number of unique accessories were planned, including a power chair that used hydraulics.[1]

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ a b c d e "Konix Multisystem: the British console that never was". Den of Geek. 23 February 2018. Retrieved 11 December 2020.

- ↑ "Konix to bring out 32-bit system". Electronic Gaming Monthly. 6 (4): 54. April 1993.

- ↑ "Slipstream: The Konix Multi-system Archive". www.konixmultisystem.co.uk. Retrieved 11 December 2020.

- ↑ a b c d "Konix Multi-System (Multisystem)". Video Game Console Library. Retrieved 11 December 2020.

- ↑ a b "OLD-COMPUTERS.COM : The Museum". old-computers.com. Retrieved 11 December 2020.

- ↑ "Slipstream: The Konix Multi-system Archive". www.konixmultisystem.co.uk. Retrieved 11 December 2020.

-

The Pioneer LaserActive with a Sega Genesis module and branded Genesis controller.

History

[edit | edit source]The Pioneer LaserActive was a LaserDisk based multimedia entertainment device with game console capabilities that was released on August 20th, 1993 at a cost of $970.[1] Unlike most multimedia platforms at the time, the LaserActive primarily played games released for other systems through PAC expansion modules, which contained a LaserActive compatible version of that console.

The Sega PAC add on was released in 1993 for $600 and allowed the LaserActive to play Genesis games.[2]

Another PAC was released to play NEC CD-ROM2 games.[1] However it was not compatible with the Arcade Card Pro.[3]

Technology

[edit | edit source]Not much information is known about the technology used by the Pioneer LaserActive itself, with most accounts focusing on the capabilities of individual PACs, which are themselves very close in capabilities to the systems they are based on.

Games

[edit | edit source]31 games were released for the LaserActive.[1] Games for the LaserActive are not region locked.[4]

Gallery

[edit | edit source]External Resources

[edit | edit source]- Nicole Express - Article describing the LaserActive in detail.

- Video Game Console Library - LaserActive page with in depth information.

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ a b c "Pioneer LaserActive". Video Game Console Library. Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- ↑ "The Weird And Wonderful World Of The Sega Genesis" (in en-us). Kotaku. https://kotaku.com/the-weird-and-wonderful-world-of-the-sega-genesis-5795188. Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- ↑ "Why did we need an Arcade Card?". nicole.express. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- ↑ "LaserActive, Gaming's Greatest Boondoggle". Wired. Retrieved 27 October 2020.

-

The Mega Duck, Cougar Boy, and games.

History

[edit | edit source]Made in Hong Kong, the Mega Duck was released in 1993.[1]

A toy laptop version of the Mega Duck was released, containing both a normal keyboard and a music keyboard, a mouse, and a printer predating the GameBoy Printer.[2]

Technology

[edit | edit source]Compute

[edit | edit source]These Mega Duck is powered by an 8-bit MOS Z80 CPU clocked at 4.19 megahertz.[3][4][5] This was a common choice at the time, and is similar to the CPU used in the original Game Boy.

The console has 16 kilobytes of RAM.[4]

Hardware

[edit | edit source]The console has a four shade monochrome LCD with a resolution of 160 by 144 pixels.[4]

The console has a six pin link port for connecting to another console over a link cable.[3]

The console is powered either by four AA batteries or a 6V DC from an AC adapter.[3]

Gallery

[edit | edit source]MegaDuck

[edit | edit source]Interior

[edit | edit source]Display

[edit | edit source]Motherboard

[edit | edit source]References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ "Feature: The Handheld Rivals Which Tried And Failed To Beat The Game Boy". Nintendo Life. 17 April 2019. Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- ↑ "Rise of the Wannabes: The Game Boy's Many Uninspired Knockoffs" (in en). www.vice.com. https://www.vice.com/en/article/kz3gjy/rise-of-the-wannabes-the-game-boys-many-uninspired-knockoffs. Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- ↑ a b c "Mega Duck / Cougar Boy - Ultimate Console Database". ultimateconsoledatabase.com. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- ↑ a b c "Gallery of Portable Gaming Systems". Video Game Console Library. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- ↑ "Mega Duck / Cougar Boy". www.progettoemma.net. Retrieved 8 December 2020.

-

The Neo Geo AES with controller.

History

[edit | edit source]

Launch

[edit | edit source]The Neo Geo AES (Arcade Entertainment System) was launched in 1990, costing the equivalent of $650 at launch.[1] In the United States of America, the Neo Geo was launched in 1991.[2]

Legacy

[edit | edit source]Samurai Shodown V Special, the last official Neo Geo cartridge, was released on April 22nd, 2004.[3]

Technology

[edit | edit source]

Compared to most home consoles of the fourth generation, the Neo Geo AES was technically superior in many aspects.[4]

Compute

[edit | edit source]The SNK Neo Geo AES is powered by a primary 16 bit Motorola 68000 processor clocked at 12 megahertz, and a secondary 8 bit Zilog Z80-A processor clocked at 4 megahertz.[5][4]

The Neo Geo AES has 64 kilobytes of RAM, 2 kilobytes of sound RAM, and 68 kilobytes of Video RAM.[5][4]

Hardware

[edit | edit source]The Neo Geo uses a custom graphics chipset which can draw 380 simultaneous sprites and three background planes simultaneously.[4]

A Yamaha 2610 chip is used for audio, and is capable of 15 channels of audio.[4]

The Neo Geo CDZ features a somewhat faster CD drive then a standard Neo Geo CD, though specific drive differences are not known.[6][7]

Notable games

[edit | edit source]1991

[edit | edit source]1994

[edit | edit source]1996

[edit | edit source]2010

[edit | edit source]Gallery

[edit | edit source]Neo Geo AES

[edit | edit source]Neo Geo CD Top loader

[edit | edit source]Neo Geo CD Front loader

[edit | edit source]Neo Geo CDZ

[edit | edit source]Controllers

[edit | edit source]Accessories

[edit | edit source]AES Internals

[edit | edit source]Neo Geo CD Top loader Internals

[edit | edit source]Neo Geo CD Front loader Internals

[edit | edit source]Neo Geo CDZ Internals

[edit | edit source]External Resources

[edit | edit source]- Video Game Console Library - SNK NEO Geo AES \ MVS Page with history, specs, and related media.

References

[edit | edit source]| Parts of this page are based on materials from: Wikipedia: the free encyclopedia. |

- ↑ "History Of: SNK". Ball State Daily. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- ↑ "5 Video Game Systems (Virtually) Everyone Forgets". CBR. 4 June 2020. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- ↑ "Title Catalogue NEOGEO MUSEUM". neogeomuseum.snk-corp.co.jp. Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- ↑ a b c d e "The History of SNK". GameSpot. Retrieved 15 November 2020.

- ↑ a b "Video Game Console Library SNK Neo Geo AES". Video Game Console Library. Retrieved 15 November 2020.

- ↑ "Neo Geo CDZ Single or Double Speed: Let's Discuss". www.neo-geo.com. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- ↑ "Will it ever stop loading?! The Neo Geo CDZ!". nicole.express. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

-

Nintendo Mini Classics Console in packaging

-

A Nintendo Mini Classic from the side, showing stand and Keychain support.

-

The back of a Mario's Cement Factory Nintendo Mini Classic, showing collapsed stand.

History

[edit | edit source]The Nintendo Mini Classics was a 1998 revival of Nintendo's prior Game & Watch concept, using much improved contemporary technology and hardware designs.[1] Some Nintendo Mini Classics games were ports of existing Game & Watch games.[2][3]

In 2009 the systems cost between $5 and $20.[4]

As the console did not rely on cutting edge technology, production continued until at least 2014,[5] making this console line among the few to be on the market for well over a decade. The Nintendo Mini Classics would later be succeeded by the Game & Watch: Super Mario Bros.

Technology

[edit | edit source]Little is known about the exact technical specs of the Nintendo Mini Classics consoles, other than that the system is capable of gameplay roughly comparable to the Game and Watch.

The production of the Nintendo Mini Classics was outsourced to external companies.[6]

The system is powered by dual LR44/AG13 batteries.[7]

Notable Games

[edit | edit source]External Resources

[edit | edit source]- FANDOM Nintendo wiki - Nintendo Mini Classics page.

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ "The Tale of Nintendo Mini Classics". Retrieved 28 February 2021.

{{cite web}}: Text "1998" ignored (help) - ↑ Jones, Elton R. (23 October 2020). "The Handheld Zelda Game You Likely Never Played". Looper.com. https://www.looper.com/266875/the-handheld-zelda-game-you-likely-never-played/.

- ↑ "Nintendo Mini Classics Keychains". Geeky Gadgets. 23 July 2009. https://www.geeky-gadgets.com/nintendo-mini-classics-keychains-23-07-2009/.

- ↑ a b c d Thompson, Michael (5 August 2009). "Nintendo Mini Classics resurrects Game & Watch titles" (in en-us). Ars Technica. https://arstechnica.com/gaming/2009/08/nintendo-mini-classics-resurrects-game-watch-titles/.

- ↑ "Nintendo Mini Classics". Wikipedia. 8 January 2021. Retrieved 28 February 2021.

- ↑ "Feature: How Nintendo's Game & Watch Took "Withered Technology" And Turned It Into A Million-Seller". Nintendo Life. 1 January 2021. https://www.nintendolife.com/news/2021/01/feature_how_nintendos_game_and_watch_took_withered_technology_and_turned_it_into_a_million-seller.

- ↑ "Nintendo Mini Classics". Nintendo. Retrieved 1 March 2021.

-

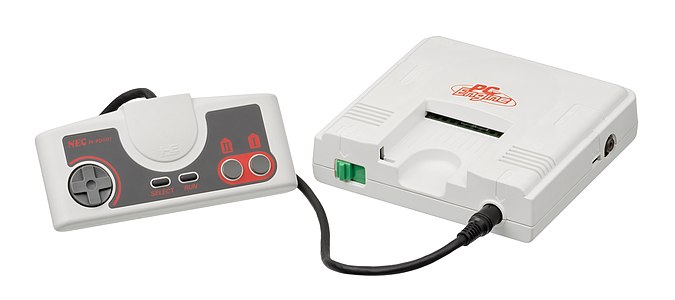

The PC Engine SuperGrafx console and controller.

History

[edit | edit source]

The PC Engine SuperGrafx was released in Japan[1] on December 8th, 1989 - just two years after the original PC Engine released in 1987.[2][3] The system was said to be released in France in May 1990.[1]

The SuperGrafx did not do well commercially, and only 75,000 consoles were sold.[2][3] A CD Add on was planned, but not released.[4]

Technology

[edit | edit source]

The PC Engine SuperGrafx uses an 8-bit HuC6280A processor clocked at 7.16 megahertz.[5][6]

The system has 32 kilobytes of RAM and 128 kilobytes of VRAM.[6]

The SuperGrafx has an extra video processor compared to the original PC Engine though bottlenecking limited performance.[7][8][9]

SuperGrafx specific games

[edit | edit source]- Aldynes[1]

- 1941: Counter Attack[1]

- Ghouls 'n Ghosts[1]

- Madö King Granzört[1]

- Battle Ace[1]

- Darius Plus (Standard PC engine compatible game, with SuperGrafx enhancements)[1]

Gallery

[edit | edit source]References

[edit | edit source]| Parts of this page are based on materials from: Wikipedia: the free encyclopedia. |

- ↑ a b c d e f g h "PC Engine SuperGrafx". Wikipedia. 2021-02-20. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- ↑ a b "Beginning a SuperGrafx Adventure". Wired. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- ↑ a b "SuperGrafx Britgamer The most detailed games database online". www.britgamer.co.uk. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- ↑ "The Console That Wasn't: The SuperGrafx CD-- Let's make it real!". nicole.express. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- ↑ "About - NEC SuperGrafx - Games Database". www.gamesdatabase.org. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- ↑ a b "OLD-COMPUTERS.COM : The Museum". www.old-computers.com. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- ↑ McFerran, Damien (6 May 2012). "The Ultimate Retro Console Collectors' Guide". Eurogamer. Retrieved 7 November 2020.

- ↑ "OLD-COMPUTERS.COM : The Museum". www.old-computers.com. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- ↑ "What on Earth is a SuperGrafx?!". nicole.express. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

-

Japanese Mega Drive with controller.

-

Sega Genesis with controller.

History

[edit | edit source]Development

[edit | edit source]The system was preceded by the Sega Master System.

Sega approached Atari about bringing the MegaDrive to the American market.[1] After negotiations broke down Sega decided to launch the console in the United States on their own.[1]

Following development of the base console a number of add on devices were developed. Development of the Sega CD was particularly problematic, with drive motors occasionally catching on fire in pre production units.[2][3]

Launch

[edit | edit source]

Japan

[edit | edit source]In October of 1988 the Sega Mega Drive was released in Japan at a cost of 21,000 yen.[4]

On May 31st, 1991 the TerraDrive computer and Mega Drive hybrid system was released in Japan.[5]

North America

[edit | edit source]The Sega Genesis was launched in North America in 1989.[6] Notably, future president of the United States Donald Trump attended the 1989 Genesis launch in Manhattan.[7]

The Genesis did very well in North American gaming market. This is especially impressive, as at launch time rival Nintendo held over 80% of the market for home video games in the United States of America,[8] and by 1990 would control over 90% of the American game market.[9] By launching quality first party exclusive games, courting unique third party developers with fewer artistic restrictions, listening to consumer feedback, and launching aggressive marketing campaigns, Sega was able to take on an entrenched industry titan and become one itself by briefly taking over half of the market for itself, An event widely considered to be one of the gaming industry's most important upsets.[10][11][12]

Worldwide

[edit | edit source]The Mega Drive saw a European release in 1990.[4]

Refresh

[edit | edit source]To make the platform more competitive, Sega would release two major add ons to expand the system's capabilities. The Sega CD was released in 1992,[13] and gave the system a CD drive with massively improved storage capacity as a result. The Sega 32x was released in November 1994 for $160,[13] and massively increased the system's raw power, though not nearly enough to be competitive with the new consoles it was meant to fend off. Both add ons would have exclusive games that could not be played on a standard Genesis or Mega Drive.

Legacy

[edit | edit source]The Genesis influenced a number of contemporary systems. The Sega Genesis was directly followed by the ill fated Sega Saturn. A portable Genesis was also made as the Nomad. A Mega Drive module was also produced for the Pioneer LaserActive.

The Sega Genesis was discontinued in 1997 outside of Brazil.[14] However the console continued to be a popular choice in certain markets after this date. Sega partner Tectoy was still selling 150,000 consoles annually as of 2016.[14] In 2016 Tectoy began taking preorders for a 2017 revision of the console for the Brazilian market at a cost of 399 Brazilian real.[15][16] In 2010 Mega Drive gaming was still popular in Egypt.[17] 29 million Sega Genesis consoles were sold.[18]

Technology

[edit | edit source]Compute

[edit | edit source]The Genesis is powered by a primary 16-bit Motorola 68000 processor clocked at 7.6 megahertz.[19] A secondary 8-bit Z80 coprocessor was clocked at 3.5 megahertz.[19]

The Genesis has 64 kilobytes of RAM dedicated to the primary processor, and 8 kilobytes dedicated to the Z80 coprocessor.[20][19]

Some games used cartridge based chips to allow for 3D graphics.[21]

The Sega Genesis was initially considered easier for developers to use then the competing SNES due to it's straightforward design instead of reliance on support hardware.[22]

Graphics

[edit | edit source]The Genesis uses a custom chip called the Video Display Processor (VDP) clocked at 13 megahertz for rendering graphics.[19] The VDP has 64 kilobytes of RAM, 128 bytes of color RAM, and 80 bytes of vertical scroll RAM.[23][19] The Genesis could render 80 sprites and 64 simultaneous colors from 512 total colors.[24]

Blast Processing was technically a feature supported by the Genesis VDP, though it was simply a technique used to generate images with more colors and was never widely used on official Genesis games.[25][26][27]

Storage

[edit | edit source]Genesis cartridges typically maxed out at 4 megabytes, though a few 5 megabyte cartridges exist.[28]

Cartridges were region locked through a combination of software and hardware methods, with mixed results and variations on usage while the console was on the market.[29]

Networking

[edit | edit source]The Sega Channel was an expensive service that allowed games to be temporarily downloaded over a cable connection.[30]

The third party X-Band service allowed some games to be played online.[31]

Notable Games

[edit | edit source]

1991

[edit | edit source]Sonic the Hedgehog

[edit | edit source]The flagship fast paced mascot platformer and system seller for the console.

Read more about Sonic the Hedgehog on Wikipedia.

Zero Wing

[edit | edit source]

Originally released as an arcade game in 1989.[32]

The Japanese version of Zero Wing had 35 different endings, a notable feat for the time.[33]

The poor English translation of Zero Wing sparked the early 2000's internet meme "All your base are belong to us".[34]

Read more about Zero Wing and All your base are belong to us on Wikipedia.

Art Alive!

[edit | edit source]An early art program for the console.[35]

Read more about Art Alive! on Wikipedia.

1992

[edit | edit source]Ecco the Dolphin

[edit | edit source]Game creator Ed Annunziata was a prolific reader of the works of scientist John C. Lilly, who closely studied dolphins.[36][37] Annunziata is also said to have been influenced by the work of musician Pink Floyd.[37]

Read more about the original Ecco the Dolphin game on Wikipedia.

1993

[edit | edit source]- Disney's Aladdin

- NBA Jam

- Mortal Kombat II - Retained the gore effects from the Arcade version.

Sonic CD

[edit | edit source]The intro movie to Sonic CD is considered by many to be iconic.[38][39]

Read more about Sonic CD on Wikipedia.

1994

[edit | edit source]Wacky Worlds

[edit | edit source]An indirect successor to Art Alive!.[40] It featured Sonic the Hedgehog and competed against Nintendo's Mario Paint.[41]

2004

[edit | edit source]CrazyBus

[edit | edit source]An infamous homebrew title.

Special edition consoles

[edit | edit source]- HeartBeat Personal Trainer- A rare North America variant of the Sega Genesis equipped with motion sensors.[42] Just 1,000 versions of this were produced, with a small number of accompanying exclusive games reliant on motion controls.[43][44]

- CSD-GM1 - CD Player with integrated Mega Drive.

Gallery

[edit | edit source]Genesis Consoles

[edit | edit source]Controllers & Accessories

[edit | edit source]Games

[edit | edit source]Genesis Internals

[edit | edit source]Development

[edit | edit source]There is a WikiBook on Genesis Programming.

External Resources

[edit | edit source]References

[edit | edit source]| Parts of this page are based on materials from: Wikipedia: the free encyclopedia. |

- ↑ a b "Feature: Remember When Atari Turned Down Nintendo And Sega?". Nintendo Life. 3 February 2020. https://www.nintendolife.com/news/2020/02/feature_remember_when_atari_turned_down_nintendo_and_sega. Retrieved 23 October 2020.

- ↑ "I'll Never Love a Console Like I Loved the Sega CD". www.vice.com. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ↑ McFerran, Damien (22 February 2012). "The Rise and Fall of Sega Enterprises". Eurogamer. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ↑ a b "HISTORY SEGA 60th Anniversary". SEGA 60th Anniversary site. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- ↑ "10 Game Consoles That Exclusively Released In Japan". Game Rant. 4 July 2021. https://gamerant.com/consoles-released-only-japan-exclusive/.

- ↑ "The Launch of the Sega Genesis (1989)". Classic Gaming Quarterly. 12 December 2016. Retrieved 14 November 2020.

- ↑ "The time President Donald Trump attended the SEGA Genesis launch in 1989". The time President Donald Trump attended the SEGA Genesis launch in 1989. Retrieved 14 November 2020.

- ↑ McGill, Douglas C. (29 June 1989). "Market Place; Nintendo Courts U.S. Investors". The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/1989/06/29/business/market-place-nintendo-courts-us-investors.html.

- ↑ "Sega v Nintendo: Sonic, Mario and the 1990's console war". BBC News. 12 May 2014. https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-27373587.

- ↑ "How Sega conquered the video games industry – and then threw it all away" (in en). The Independent. 31 March 2020. https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/games/sega-sonic-hedgehog-nintendo-sony-video-game-a9334771.html.

- ↑ "The Radical Environmentalism of the Sega Genesis" (in en). www.vice.com. https://www.vice.com/en/article/wnzdk9/the-radical-environmentalism-of-the-sega-genesis.

- ↑ Krisch, Joshua A. (13 May 2014). "How Sega vs Nintendo Became a Billion-Dollar Rivalry". Popular Mechanics. https://www.popularmechanics.com/culture/gaming/a10516/how-sega-vs-nintendo-became-a-billion-dollar-rivalry-16787174/.

- ↑ a b Forsythe, Dana (19 June 2019). "Sega's 32X was one of video gaming's biggest disasters". SYFY WIRE. Retrieved 14 November 2020.

- ↑ a b "Sega's Genesis (known outside of North America as the Mega Drive) to re-enter production". TechSpot. Retrieved 14 November 2020.

- ↑ Hall, Charlie (9 November 2016). "Temper your enthusiasm for the new Sega Genesis". Polygon. Retrieved 14 November 2020.

- ↑ "TecToy unveils its new limited edition SEGA Genesis | SEGA Nerds". Retrieved 14 November 2020.

- ↑ "Videogames of Egypt". Retrieved 8 November 2020.

- ↑ "Genesis vs. SNES: By the Numbers - IGN". Retrieved 13 November 2020.

- ↑ a b c d e "Mega Drive Architecture A Practical Analysis". Rodrigo's Stuff. 18 May 2019. Retrieved 7 November 2020.

- ↑ "Winning The Console Wars – An In-Depth Architectural Study". Hackaday. 6 November 2015. https://hackaday.com/2015/11/06/winning-the-console-wars-an-in-depth-architectural-study/. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- ↑ "The Great Polygon Mystery". www.gamezero.com. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- ↑ "It's no SNES". www.gamezero.com. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- ↑ "First steps with the Sega MegaDrive VDP Marc's Realm". darkdust.net. Retrieved 7 November 2020.

- ↑ "WAR! - Nintendo Vs. Sega". www.gamezero.com. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- ↑ Linneman, John (31 March 2019). "Sega's legendary Blast Processing was real - but what did it actually do?". Eurogamer. Retrieved 7 November 2020.

- ↑ Life, Nintendo (20 November 2015). "The Man Responsible For Sega's Blast Processing Gimmick Is Sorry For Creating "That Ghastly Phrase"". Nintendo Life. Retrieved 7 November 2020.

- ↑ Life, Nintendo (4 May 2020). "Sega's Blast Processing? We Did It On The SNES First, Says Former Sculptured Software Dev". Nintendo Life. Retrieved 7 November 2020.

- ↑ "A Brief and Abbreviated History of Gaming Storage – Techbytes". Retrieved 18 October 2020.

- ↑ "Trademarks and Region Locks on the Sega Genesis". nicole.express. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- ↑ "The Sega Channel Blew My Ten-Year-Old Mind" (in en-us). Kotaku. https://kotaku.com/the-sega-channel-blew-my-ten-year-old-mind-1792825606. Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- ↑ "X-BANDing". www.gamezero.com. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- ↑ ""Gameography" in "Metagaming" on Manifold @uminnpress". Manifold @uminnpress. Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- ↑ "The "All Your Base" Game Had 32 Secret Japanese Endings". Kotaku. Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- ↑ "25 years later, 'All Your Base Are Belong to Us' holds up". The Daily Dot. 4 June 2016. Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- ↑ "Art Alive!". Sega Retro. 2021-05-01. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- ↑ "The Ketamine Secrets of ‘Ecco the Dolphin’" (in en). www.vice.com. https://www.vice.com/en/article/exmjpz/the-ketamine-secrets-of-segas-ecco-the-dolphin-347.

- ↑ a b Jex, Shaun (19 January 2019). "A Momentary Lapse of Reason: The Story of Ecco - Old School Gamer Magazine". https://www.oldschoolgamermagazine.com/a-momentary-lapse-of-reason-the-story-of-ecco/.

- ↑ "The greatest video game animated opening of all time is more beautiful than ever in this HD upscale of Sonic CD's intro". Nintendo Wire. 10 February 2021. https://nintendowire.com/news/2021/02/10/the-greatest-video-game-animated-opening-of-all-time-is-more-beautiful-than-ever-in-this-hd-upscale-of-sonic-cds-intro/.

- ↑ "Iconic Sonic CD Intro Has Been Remastered To 720p By Fans". TheGamer. 8 February 2021. https://www.thegamer.com/sonic-cd-intro-remaster/.

- ↑ "Wacky Worlds". Sega Retro. 2021-05-19. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- ↑ "The Story of Mario Paint | Gaming Historian". Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- ↑ "HeartBeat Personal Trainer". Sega Retro. 2019-06-04. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- ↑ "10 Rarest Console Exclusive Games (& How Much They're Worth)". TheGamer. 2020-05-11. https://www.thegamer.com/rarest-console-exclusive-games-how-much-worth/.

- ↑ Hosie, Ewen (2017-08-20). "Near mint: A conversation with game collectors" (in en). Eurogamer. https://www.eurogamer.net/articles/2017-08-20-near-mint-a-conversation-with-game-collectors.

- ↑ "J-Cart". Wikipedia. 28 January 2021. Retrieved 24 February 2021.

-

An opened Sega Pico, showing a book cartridge installed.

History

[edit | edit source]The Sega Pico was initially released in June of 1993.[1]

The Sega Pico was released in the USA in 1994.[2]

In 1995 the Sega Pri Fun printer was released for the Pico and Saturn.[3][4]

The Pico sold poorly in North America, but was better received elsewhere with 3.4 million consoles sold by 2005.[5]

On August 5th, 2005 the Advanced Pico Beena was released in Japan.[6]

Technology

[edit | edit source]

Aside from lacking a Z80 processor and a Yamaha sound chip, and adding a DMA chip for audio, the Pico has similar specifications to the Mega Drive or Genesis.[7][8]

The pen uses a microswitch to detect presses.[9]

Special Editions

[edit | edit source]- Sega Pico Pikachu Edition[10]

Notable games (Storyware)

[edit | edit source]For more listings see the List of Sega Pico games on Wikipedia.

2002

[edit | edit source]- Pokémon: Catch the Numbers!

2003

[edit | edit source]- Pokémon Advanced Generation: I've Begun Hiragana and Katakana!

2004

[edit | edit source]- Pokémon Advanced Generation: Pico for Everyone Pokémon Loud Battle!

External Resources

[edit | edit source]- Game Medium - Advanced Pico Beena page.

References

[edit | edit source]| Parts of this page are based on materials from: Wikipedia: the free encyclopedia. |

- ↑ "HISTORY SEGA 60th Anniversary". SEGA 60th Anniversary site. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- ↑ "Game Systems". www.lib.umich.edu. Retrieved 30 October 2020.

- ↑ "Printing Fun-Fun with Sega Pri Fun". retrostuff. 6 March 2016. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- ↑ "Pri Fun". Sega Retro. 15 September 2020. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- ↑ "Sega Pico (1993 - 2005)". Museum of Obsolete Media. 17 November 2019. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- ↑ "Consolevariations - Sega Pico Advanced Beena Console". Consolevariations. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- ↑ "Sega Pico - Game Console - Computing History". www.computinghistory.org.uk. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- ↑ "Sega Pico". Sega Retro. 31 October 2020. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- ↑ "Sega Pico Pen Repair". retrostuff. 31 March 2019. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- ↑ "10 Hardest To Find Limited Edition Versions Of Consoles (& How Much They're Worth Today)". Game Rant. 21 November 2019. https://gamerant.com/rare-limited-edition-consoles-worth-value-price/.

-

The SuperA'Can console with controller attached.

History

[edit | edit source]The console was developed by the Taiwanese company FunTech.[1]

The Super A'Can was released on October 25th, 1995 only in Taiwan.[2][3] The system did not sell well, cost it's maker Funtech 6 million dollars, and unsold units were scrapped for parts.[4]

Technology

[edit | edit source]

The Super A'Can used a 16 bit Motorola 68000 as its primary processor clocked at 10.6 megahertz.[3][5][2] Some sources list an 8 bit Motorola 6502 as a secondary processor clocked at 3.58 megahertz,[2][5] though a discrete official Motorola version of this chip is absent from the board, meaning it is integrated in another chip if present.

The Super A'Can has 64 kilobytes of RAM and 128 kilobytes of video RAM.[2]

The system sports a dedicated support chips that were manufactured by UMC, including the UM6618 graphics chip, and the UM6619 audio chip.[6]

The Super A'Can outputs 16 track PCM audio in stereo.[6]

Design

[edit | edit source]Console

[edit | edit source]The Super A'Can is a boxy grey console featuring both angular and smooth arching accents. Cartridges are loaded from the top of the device, which also features a power toggle, an eject button, and a reset button. The front of the console has two controller ports, which appear to be D-Sub 9 ports, similar to those used on the Atari 2600 and the Sega Mega Drive / Sega Genesis. Appropriately, on the port side of the console there is an expansion port. The console rear features vents, as well as IO including red, white, and yellow coded RCA jacks for high quality video output, an RF port for lower quality video output to older or lower end televisions, and a power input jack.

Controller

[edit | edit source]The official wired controllers sport a design similar to the controllers used by the Super Famicom / Super Nintendo Entertainment System, but with more curves. The controller sports a somewhat unique light purple direction pad on the left side, with a inner shield that does not quite reach the outer edges of the primary directions. The primary face buttons are on the right side of the controller are arranged in a diamond pattern, and include a red "Y" button on the top, a yellow "B" button on the right, a blue "A" button on the bottom, and a green "X" button on the left of the controller. The center of the controller features two oblong grey buttons, select on the left, and start on the right. The console logo and text "A'Can" are embossed on the upper center of the controller, just over where the cable connects on the back. The back of the controller features light purple L & R buttons, lightly labeled in the same color on the button itself, rather then in white next to the button as on the rest of the controller. On the bottom of the controller there is a turbo switch, as well as 6 screw holes screw holes. The back of the controller also features slight angles near the end, likely intended to offer an ergonomic grip.

Notable games

[edit | edit source]12 games exist for the Super A'Can.[3]

1995

[edit | edit source]Gallery

[edit | edit source]Console

[edit | edit source]Accessories

[edit | edit source]Motherboard

[edit | edit source]Internals

[edit | edit source]References

[edit | edit source]| Parts of this page are based on materials from: Wikipedia: the free encyclopedia. |

- ↑ "Why The Super A'Can Failed! - Rare Console History". Retrieved 1 March 2021.

- ↑ a b c d "Super A'Can". Video Game Console Library. Retrieved 22 November 2020.

- ↑ a b c "ARCHIVE.ORG Console Library: Super A'Can : Free Software : Free Download, Borrow and Streaming : Internet Archive". archive.org. Retrieved 25 October 2020.