Exercise as it relates to Disease/Effectiveness of home-based exercise in patients with advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

This is a critique of the journal article titled the ‘Effectiveness of home-based exercise in older patients with advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A 3-year cohort study’ by Wakabayashi, Kusunoki, Hattori, Motegi, Furutate, Itoh, Jones, Hyland, & Kida (2017). [1]

What is the background to this research?[edit | edit source]

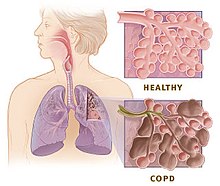

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a broad term used to describe progressive lung diseases such as emphysema, chronic bronchitis and refractory asthma. [2] COPD is characterised by respiratory symptoms such as:

- dyspnea (breathlessness);

- shortness in breath;

- airflow obstruction;

- wheezing;

- coughing; and

- tightness in the chest.[2] [3]

Contributing factors that lead to COPD include inflamed and damaged bronchi and alveoli of the lungs. [3] In severe cases, COPD can lead to disability, hospitalisation and mortality.[4] COPD cannot be cured, however it can be treated through:

- medications;

- oxygen therapy; and

- pulmonary rehabilitation. [2]

In the ageing population, COPD is strongly linked to a patient’s reduction in exercise.[1] Physical inactivity in patients can lead to muscular weaknesses (upper and lower limbs), atrophy and poor physical health. [1] COPD patients are often referred to pulmonary rehabilitation programs to increase quality of life, build exercise tolerance and muscle strength, and to reduce respiratory exacerbations and hospitalisations. Pulmonary rehabilitation includes prescribed exercise programs that are delivered in consultation with health professionals. [1] [5] [6]

Information in this study is relevant to Australia's ageing population. For example, in 2017, there were 3.8 million Australians aged 65 and over[7], and in 2014, 1 in 7 people aged 40 years and over reported respiratory symptoms or airflow obstruction.[8]

Where is the research from?[edit | edit source]

This research was conducted between January 2008 and December 2012 in Japan. The research was developed by Ritsuko Wakabayashi, Yuji Kusunoki; Kumiko Hattori, Takashi Motegi, Ryuko Furutate, Aki Itoh, Rupert CM Jones, Michael E Hyland and Kozui Kida.[1]

The article was accepted and published in 2017, in the Geriatrics & Gerontology International Journal (the official journal of the Japan Geriatrics Society). [1] Geriatrics & Gerontology International appear to have a sound reputation and is active in providing information to national and international congresses held within Asian countries to advocate ideas of shared interest within the scope of geriatrics and gerontology.[9]

What kind of research was this?[edit | edit source]

This study is a prospective three-year cohort study investigating the effects of home-based exercise in older patients with COPD. [1]

What did the research involve?[edit | edit source]

The research involved 136 COPD patients (with a mean age of 74.2 years) either selecting home-based exercise using an ergo-bicycle (Group E), or usual exercise (Group U). The samples for each group were large, with 72 patients in Group E and 64 participants in Group U. [1]

Patients in Group E were required to purchase an ergo-bicycle and were instructed to use it once per day for twenty minutes, with oxygen inhalation. Patients were asked to increase their heart rate to approximately 80 per cent of their six-minute walk test during exercise sessions. [1]

Patients in Group U were instructed to conduct usual exercise once per day for 20 minutes, with exercise intensity between 3 and 4 on the modified Borg Scale. Portable oxygen cylinders were used by participants. [1]

Both groups were requested to keep a record of the completed exercise sessions and any symptoms experienced that were associated with the exercise.[1]

Data and information regarding patient clinical outcomes was collected through a range of benchmark exercise and physiological tests and scales. [1]

What were the basic results?[edit | edit source]

Researchers found that patients in Group E who were undertaking home-based exercise using the ergo-bicycle saw more positive clinical outcomes than patients who were in Group U and conducting usual exercise. To support this, the total score on the Lung Information Needs Questionnaire in Group E significantly improved over the three years, whereas Group U saw no change in score. Group E also demonstrated a reduction in exacerbations over the three-years.[1]

With regards to the six-minute walk test, Group E was able to maintain their walking distance whereas Group U patients had a decline in distance (47.7 metres over three years).[1]

Forced expiratory volume in one second at benchmark was lower in Group E, however was maintained over the three-year period. Group U saw a significant reduction over the three years on this test.[1]

Body mass index, airflow obstruction, dyspnea and exercise index worsened in both groups over the three-year period. However, no differences were seen in hospitalisations over the three-year period between the two groups.[1]

What conclusions can we take away from the research?[edit | edit source]

This article provides evidence that moderate exercise is beneficial for treating older patients with COPD.[1]

Similar studies have been conducted which also support the clinical outcomes of this study. For example, a twelve-week exercise counselling program using a pedometer showed positive enhancements in patients’ physical fitness and quality of life, compared to patients who did not participate in the program.[10]

Methods contained within this study appear to be consistent with other research articles. [4] [5] [6] Contrary to this, it was noted that this study does not include a sit to stand test, which would have been useful to better understand patient’s adaptations in lower limb strength, balance and transfer skills. [6]

In light of the positive outcomes of the study, the researchers indicated that the study may have had some bias and flaws. For example, patients were able to choose their exercise group, meaning patients in Group E may have been more motivated to exercise, skewing results. [1]

Some additional flaws to note as part of this critique:

- patients in Group U may have interpreted the Borg scale and exercise intensity differently;

- there is no definition of usual exercise; and

- benefits of home-based training not explained.

Noting the above issues, and when comparing to other studies, this research draws a weak conclusion.

Practical advice[edit | edit source]

Based on information contained within this study, and similar studies, COPD can be treated with moderate exercise.[1][4] [5] [6] [10] However, prior to commencing an exercise program, it is recommended that clearance is obtained from a health professional, to ensure it is safe to do so. [2] [3] [8]

Other practical tips to assist in managing COPD include:

- quitting smoking;

- having a yearly influenza and pneumococcal immunisation;

- maintaining a healthy weight; and

- developing an emergency plan, should exacerbations occur. [2] [3].

In addition to this, patient support groups are also operating such as the Lungs in Action Program, facilitated by the Lung Foundation Australia.[8]

Further information[edit | edit source]

For more information on how to treat and manage COPD, please visit:

- Factsheet: Lung Foundation Australia - What is COPD? [8]

- Lungs in Action Program – community based exercise program for people with stable chronic lung conditions.[11]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Wakabayashi, R., Kusunoki, Y., Hattori, K., Motegi, T., Furutate, R., Itoh, A., Jones, R., Hyland, M. and Kida, K. (2017). Effectiveness of home-based exercise in older patients with advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A 3-year cohort study. Geriatrics & Gerontology International, 18(1), pp.42-49.

- ↑ a b c d e The COPD Foundation, What is COPD?, 2018, Webpage, Accessed 16 September, https://www.copdfoundation.org/What-is-COPD/Understanding-COPD/What-is-COPD.aspx

- ↑ a b c d Victoria State Health, Lung conditions - COPD, Webpage accessed 16 September 2018, https://www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au/health/conditionsandtreatments/lung-conditions-chronic-obstructive-pulmonary-disease-copd

- ↑ a b c Kawagoshi, A., Kiyokawa, N., Sugawara, K., Takahashi, H., Sakata, S., Satake, M. and Shioya, T. (2015). Effects of low-intensity exercise and home-based pulmonary rehabilitation with pedometer feedback on physical activity in elderly patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respiratory Medicine, 109(3), pp.364-371.

- ↑ a b c Mazzarin, C., Kovelis, D., Biazim, S., Pitta, F. and Valderramas, S. (2018). Physical Inactivity, Functional Status and Exercise Capacity in COPD Patients Receiving Home-Based Oxygen Therapy. COPD: Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, pp.1-6.

- ↑ a b c d Li, P., Liu, J., Lu, Y., Liu, X., Wang, Z. and Wu, W. (2018). Effects of long-term home-based Liuzijue exercise combined with clinical guidance in elderly patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Clinical Interventions in Aging, Volume 13, pp.1391-1399.

- ↑ Australian institute of Health and Welfare, Older Australia at a Glance, Webpage, accessed 16 September 2018, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/older-people/older-australia-at-a-glance/contents/demographics-of-older-australians/australia-s-changing-age-and-gender-profile

- ↑ a b c d Lung Foundation Australia, COPD Factsheet, Webpage accessed 16 September 2018, https://lungfoundation.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/COPD_FS-Sep2015.pdf

- ↑ Geriatrics & Gerontology International 2018, Webpage, accessed 16 September 2018, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/page/journal/14470594/homepage/productinformation.html .

- ↑ a b Hospes, G., Bossenbroek, L., ten Hacken, N., van Hengel, P. and de Greef, M. (2009). Enhancement of daily physical activity increases physical fitness of outclinic COPD patients: Results of an exercise counseling program. Patient Education and Counseling, 75(2), pp.274-278.

- ↑ Lung Foundation Australia, Lungs in Action Program, Website accessed 16 September 2018, https://lungsinaction.com.au/,