User:Manuela.Irarraz/sandbox/Approaches to Knowledge/Seminar Group 8/Disciplinary Categories

Disciplinary Categories[edit | edit source]

The most commonly used approach to the coherency and organisation of knowledge is via Disciplinary Categorisation[1]. This is essentially the establishment of distinct academic fields, that have been generated by the classification of our knowledge, in order to ascertain similarities and differences. This involves identifying theories, methodologies and perspectives of topics which characterises a certain discipline. Thus, classification and Disciplinary Categories are intimately linked.

Discussions about this method of categorisation have taken place since the days of Aristotle[2], and has once again been emphasised, in terms of whether it is sustainable enough to encapsulate the growth of knowledge in the way it has over recent years, especially due to its increasingly interdisciplinary nature. It is notable then to consider the impact of the “strict maintenance of boundaries”[1] between different Disciplinary categories.

Definition and Etymology[edit | edit source]

The word 'disciplinary' stems from the word 'discipline', meaning a 'branch of instruction or education'. Its first use in English was in the late 14th century. Discipline comes from the Latin discipulus, meaning pupil, and disciplina meaning teaching, learning, knowledge or instruction given[3]. The word 'category' can be defined as a division of things regarded as having particular shared characteristics [4], it is defined by Aristotle's logic as a "highest notion"[5]. It originates from the Middle French catégorie, from the Latin categoria, borrowed from the Greek kategoria meaning a class of predicables [6] or an accusation. This stems from the Greek verbal noun kategorein, "to speak against, to accuse or predicate", from kata meaning 'down to' or 'against' and from agora meaning 'public assembly'[7].

Notable Views[edit | edit source]

Aristotle's Work[edit | edit source]

The concept of Disciplinary categories stems back from the works of the philosopher, Aristotle, who created categories according to “Substance, Quantity, Quality, Relation, Place, Date, Posture, State, Action and Passion”, [8] which rather than defining certain scholarly disciplines as such, instead outlines terms used to describe a broad range of information that is being expressed.

Aristotle himself gave no indication of the foundations from which he came up with these categories. It is suggested by J.L. Ackrill, in his book 'Aristotle: Categories and De Interpretatione'[9] that Aristotle had done so by taking into consideration the types of questions that are being put forward, and how that information may then be sorted into these groups to make it more useful and efficient for a person who is seeking those answers. This theory is known as the Question Approach. Numerous other interpretations have also been put forward, which have been divided into three other groups alongside the Question Approach, including the Grammatical Approach, the Modal Approach, and the Medieval Derivational Approach.[10]

It is notable to compare this to the common, current categorisation by discipline, where beginning to answer a question using this system would call for a much wider, perhaps longer, search, since the information that needs to be sought after, is divided into the disciplines from which the notions are sourced. It has been suggested that Aristotle’s categories may be helpful in the way of perhaps rethinking certain structures that constitute Disciplinary categorisation, and further refining a user’s search in terms of considering, in a descriptive sense, the knowledge that they seek, and thereon which category that would be assigned to. [11]

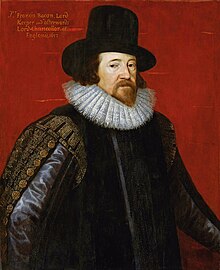

Francis Bacon (1561-1626)[edit | edit source]

Sir Francis Bacon was an English lawyer and philosopher amongst other roles who dedicated his interests to re-establishing new ways of producing knowledge that will be efficient to use. [12]

Bacon published eight books reviewing his thoughts on the process of learning, in which he strongly put forward the importance of interlinking ideas between the set boundaries of each branch of knowledge. Even though he himself devised a categorisation for organising knowledge, he believed that all knowledge in science is in fact connected with one another, therefore, we should be keeping a holistic look upon it. [13]

Hume's Fork[edit | edit source]

Philosopher David Hume proposed the concept of a two pronged fork that divided knowledge. It can be loosely divided by knowledge learnt from a priori or a posteriori knowledge. A priori is Latin for "from what is before", when used in this context it refers to knowledge which can be known without and prior experience. Alternatively, A posteriori is Latin for "from what is after" as it refers to knowledge that is gained through experience[14]. He proposed that all knowledge was spilt into two categories, they are as follows:

- Analytic statements known through apriori knowledge. These necessary statements are understood through reason alone, or pure reason. E.g All bachelors are unmarried. By reading the word bachelor one understands this to mean a man with no spouse therefore the statement answers itself and required no further testing to prove its validity.

- Synthetic statements known through a posteriori knowledge, these are also referred to as contingent statements. This kind of knowledge is gained through empirical evidence and sense experience. Eg. It is raining today. One would have had to experience the rain on that day to know that to be true. [15]

Analytic statements are those which knowledge can be understood simply through the definitions of all terms in the sentence whereas synthetic terms rely on knowledge outside of simply the definition to inform you on whether the statement is true or not. For example, " all millionaires are rich" would be analytical whereas "all lawyers are rich" relies upon a certain understanding of the world to inform whether or not the statement is true. [16]

Education and Categories[edit | edit source]

Birth and Evolution of the Humanities[edit | edit source]

The Humanities are at the centre of education across the world; aiming to decipher and understand human behaviour all whilst recording human history, the humanities encompass subjects such as history, philosophy, literature, art, music and language[17]. From the old French humanité itself derived from the latin term humanitas meaning humankind or human nature. The term humanitas is actually a derivative of the term humanus which can be described a as state or quality of being human; the word was first introduced to the Latin world by roman orator Cicero.

Birth and Evolution of the Sciences[edit | edit source]

The term 'science' is seen to have derived initially from the PIE root "skei-" meaning to "cut, split". In Latin, the word "scientia" carried a meaning of "knowledge, a knowing; expertness". The word "science" then emerged in the 12th century, in Old French, derived from Latin, and means to possess qualities of the application of knowledge. By the 14th century, "science" was considered to be a "particular branch of knowledge" with a sense of expertise; in that it is taught and studied as a discipline based on proven facts gained by experimentation, as well as theories. The distinction of science from the arts is notable from the 1670s. [18]

It is notable that the evolution of the sciences has been shaped by the issues and problems being raised in society, and this, of course, changes overtime. Initially, as scientific knowledge was growing, alongside the development of technology that allowed scientists and researchers to acquire new information, traditional scientific disciplines essentially thrived on their own. However, the urgency to address certain problems, such as climate change, has stimulated the need for scientific disciplines to work together. In 1976, Russell W. Peterson was noted to have mentioned how it was important for the sciences to naturally be able to act in an interdisciplinary manner, in order to efficiently seek solutions to the way in which environmental protection should be handled, considering both the ecology and the interests of the public sphere. [19] Thus, he highlights the importance of this collaboration not only within the natural sciences, but also between the natural and the social sciences, in order to confront the current issue at hand. This is just one example of many, where scientific disciplines are encouraged to essentially go beyond their own 'categories' in order to create new links of information.

At present day, there are 4 independent standing of natural sciences [20], these are:

- Physics: attempts to explain matter, including the form it takes as well as it interactions with the materials it exists in in the universe, in order to build laws of nature theories [21]

- Chemistry: looks at the make up of matter from its constituent parts, its characteristics as one element, how it interacts with other compounds and formulation of different compounds [22]

- Biology: explores living organisms and its interactions in the biotic and abiotic environment [23]

- Psychology: investigates the human mind including how it dictates human behaviour [24]

Primary and Secondary Education - Subjects and Curricula[edit | edit source]

Variations Across Cultures[edit | edit source]

Ancient China[edit | edit source]

The classification of knowledge in ancient China is notably different compared to the way the western world classifies knowledge. It was not intended to correspond to academic disciplines, instead focusing on creating a paradigm of Chinese society and its people.[25] These categories are multidisciplinary in nature as it seeks to be a reflection of the lives of the Chinese civilization. [26] Chinese traditional classification of knowledge was first established in sixth century B.C., but eventually manifested itself as the "four-division system" during the Tang dynasty (618-907 AD).[27] This continued to dominate Chinese academia until the 16th century. Knowledge was divided into four categories: classical canons and commentaries (jing), history and related subjects (shi), philosophy or masters (zi) and arts and collections of fine writings (ji). [28] Historian Bernard Luk notes, "This system was based on the Confucian approach to scholarship - the Classics express the Way in words, history in deeds, while philosophers and literary artists illustrate various other aspects of the Way."[29] This system remained the dominant system and peaked in the Qing dynasty when the Complete Library of Four Sections (四库全书, si kuan quan shu) was completed in 1789. [30] It is the largest collection of books in Chinese history, and each item is divided into the four main categories, and each division is again divided into subdivisions, totaling in 67 divisions. [31] This system lasted till the turn of the 20th century, and historians believe that the classification system survived as it reflected the Chinese worldview and its values, and only changed when the core values reflected in the system changed as Confucianism is less important in the society by then. [32]

Ancient India[edit | edit source]

When looking at the classification of knowledge in Ancient India, it is useful to note that it was hugely influenced by the religious beliefs of the time, since there was a cultural significance placed on the retrieval of education, which therefore naturally infused the religious teachings in academic institutions. [33] This occurred ever since the Vedic civilisation (1500-500 B.C.E). [34] Two of the oldest universities in the world are located in India being the Takshashila (Taxila) and Nalanda. Religious teachings in Ancient India varies across institutions, which include teachings of “Bauddha Dharma (Buddhism), Jina Dharma (Jainism), and Sanatana Dharma (Hinduism)”. [33]

In Sanskrit, the term “Vidya” (विद्या) carries the meaning of ‘knowledge’ and ‘learning’. [35] In Ancient India, this knowledge was further divided into the “lower Apara Vidya” which constitutes academic learning as well as objective knowledge, and the “higher Para Vidya” which is about spiritual knowledge (regarding the “Atma” (आत्मा, आत्मन्) [36] that refers to the “inner soul”, and of “Brahman” (ब्रह्मन्)). [37]

The two dominant types of education systems known in Ancient India were the Vedic System (which was taught in the Sanskrit Language) and the Buddhist system (which was taught in the Pali language). It is notable that they differ from the modern system of education in terms of their purpose, which both systems shared, in not only just relaying knowledge, but with the ultimate aim to provide “liberation” for individuals, [38] as well as “self-fulfillment” and personal development. [39]

The Vedic education system categorised knowledge into five major streams (known as Vidyas विद्या) which all were required to be studied by individuals, and these were:

1) Sabda-vidya (Vyakarana) – which entailed grammar and lexicography

2) Silpasthanavidya – constituted of arts and crafts

3) Chikitsavidya – science of medicine

4) Hetuvidya – the study of logic

5) Adhyatmavidya – associated with philosophy [40]

After this, students were allowed to specialise in a field of knowledge, much like the modern system of education today. Notably, even if one wanted to have a career associated in the humanities, for example, it was still made compulsory for them to study ‘Chikitsavidya’ (Medical sciences), as it was seen as a crucial foundation of knowledge that students should attain, and this same principle applies to the compulsory study of ‘Silpasthanavidya’ too. [40]

The Buddhist system shared similar traits to the Vedic system, and predominately categorised knowledge according to specific skills that were taught to students including dancing, weaving, and music, which then progressed to academic disciplines including Philosophy, Medicine and Military Science, but overall were further linked to the religious knowledge that was thoroughly infused into the education. [41]

Significance of Classification in Contemporary Society[edit | edit source]

Information and Library studies[edit | edit source]

In a library, each resource (or book) is categorised; in other words, sorted into distinct groups that we create. Categorisation is a method to organise our knowledge, under certain headings (which illustrate its main topic). This allows us to access pieces of information more quickly and efficiently.

Sometimes, it is difficult to classify and even recognise, if one material or aspect of knowledge is in one category or another. That is because one resource can cover multiple disciplines, and can exist within multiple categories. 'Categorisation' of one material, reveals our understanding of it, but that understanding can also change through time. As Let’s Not Homosexualize the Library Stacks”: Liberating Gays in the Library Catalog[42] states, libraries stand a critical role to shape the knowledge within the public sphere, and its arrangement and design determines our boundaries across different disciplines, in other words, our 'classification' of knowledge.

Despite categorisation in libraries having the useful purpose of establishing connections between written material that share similar characteristics in nature, it is notable that it simultaneously draws a line of separation between a certain piece of work and others that have not been chosen to belong to that classified group. [43]

Melissa Adler, in her book ‘Cruising the Library: Perversities in the Organization of Knowledge’, further adds how “subject headings” that are created in a library in order to categorise material, are essentially “subjectifying mechanisms”, since it has been determined via the perspective of a certain body/person, by different means, that the subject heading is sufficient to pertain to the knowledge that is being expressed in the writings that have been assigned to that category. [43]

Although, as of the emerging technology and modern communication platforms including online research tools become more common, physical visits to libraries become less unnecessary. Melvil Dewey, an American educator and librarian, criticizes the accessibility of modern resources as follows: "The cheapness and quickness of modern methods of communication had been like a growth of wings, so that a thousand things which were thought to belong like trees in one place may travel about like birds"[44]

W.K.Butts work[edit | edit source]

"Classification means distributing into groups according to characteristics held in common"[45] according to Butts humans naturally arrange ideas into an orderly manner. Butt argues that by categorising our ideas and processes it aids our mental capacities and develops a good basis for thinking. The human brain would not to able to function if it did not naturally and unconsciously classify its ideas. Furthermore, he states that "a good classifier tends to be a good thinker; likewise a good thinker is likely to be a good classifier".[45]

By specialising in a domain we learn to classify in a logical and accurate manner. Hence, we discriminate the information that does not correspond to the criteria in question. Human brains pick up the "language" utilised and identify to which category it corresponds. According to Butts if we fail to do so, the consequences could be dramatic as we would lean towards wrong decisions and conclusions.

Interdisciplinary Studies[edit | edit source]

Interdisciplinary studies involve the incorporation of two or more academic, scientific or artistic disciplines [46]. Alongside exists the terms multidisciplinarity and transdisciplinarity. These terms work to describe the interaction of academic disciplines to varying degrees on the same continuum.

Whilst interdisciplinarity ‘analyzes, synthesizes and harmonizes’ elements from different disciplinary categories, multidisciplinarity uses knowledge drawn from separate disciplines whilst remaining within the boundaries of those fields [47]. Transdisciplinarity, often connoting to research, involves the integration of multiple disciplines to form new ideas [48], through Emergence.

Thus the summative words for interdisciplinarity, multidisciplinarity, and transdisciplinarity could be additive, interactive and holistic, respectively [49].

The collective aim of these forms of study is to create new ways of working, stimulating the emergence of new knowledge.

Advocation for Interdisciplinary studies[edit | edit source]

Alan Wilson, in his book 'Knowledge Power: Interdisciplinary education for a complex world', outlines two main types of interdisciplinary studies, which are both useful in generating new forms of knowledge, and applying them to solve issues.

Firstly, there are interdisciplinary studies with a "systems focus". [50] This form of interdisciplinary study typically arises due to a certain problem, that requires the input and collaboration of different disciplines to arrive at an effective way to solve it, or to gather more information. Examples include, textiles (which would involve the disciplines of chemistry, engineering, business and fashion) and transport, which would entail economic, geographical and other social science-based perspectives. A particular ongoing issue that this interdisciplinary approach could be applied to is climate change. [50]

Secondly, there are "Conceptual" interdisciplinary approaches. This is when a concept, that has derived from a particular discipline, is applied to another discipline, to help think of new solutions to problems, and create new strands of knowledge. When a concept is used in this way, it is referred to as a "superconcept" (a term that was coined by Alan Wilson). For example, the concept of 'Evolution' originates from Biology, and can be applied to other disciplines, such as Art, by using the main principles that define the concept. Wilson suggests that working with an interdisciplinary approach, by utilising concepts across disciplines, in order to solve problems that arise, could be a more useful alternative, instead of generating numerous "specialist (sub) disciplines". [50]

Notes[edit | edit source]

- ↑ a b Lal, Vinay. “Modern Knowledge and Its Categories.” Empire of Knowledge: Culture and Plurality in the Global Economy, Pluto Press, LONDON; STERLING, VIRGINIA, 2002, pp. 103–130. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt18fs8fk.8.

- ↑ Thomasson, Amie, "Categories", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2018 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2018/entries/categories/>

- ↑ Etymonline.com. (2018). discipline | Origin and meaning of discipline by Online Etymology Dictionary. [online] Available at: https://www.etymonline.com/word/discipline [Accessed 22 Oct. 2018].

- ↑ Oxford Dictionaries | English. (2018). category | Definition of category in English by Oxford Dictionaries. [online] Available at: https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/category [Accessed 22 Oct. 2018].

- ↑ Etymonline.com. (2018). discipline | Origin and meaning of discipline by Online Etymology Dictionary. [online] Available at: https://www.etymonline.com/word/discipline [Accessed 22 Oct. 2018].

- ↑ Perseus.tufts.edu. (2018). Charlton T. Lewis, Charles Short, A Latin Dictionary,cătēgŏrĭa. [online] Available at: http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:1999.04.0059:entry=categoria [Accessed 22 Oct. 2018].

- ↑ Etymonline.com. (2018). category | Origin and meaning of category by Online Etymology Dictionary. [online] Available at: https://www.etymonline.com/word/category#etymonline_v_5485 [Accessed 22 Oct. 2018]..

- ↑ Plato.stanford.edu. (2018). Categories (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy/Spring 2018 Edition). [online] Available at: https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2018/entries/categories/ [Accessed 22 Oct. 2018].

- ↑ Ackrill, J. L. (1965). Aristotle's Categories and De Interpretatione.

- ↑ Plato.stanford.edu. (2018). Aristotle's Categories (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy/Fall 2018 Edition). [online] Available at: https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2018/entries/aristotle-categories/ [Accessed 22 Oct. 2018].

- ↑ Jansen, L. Topoi (2007) 26: 153. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11245-006-9009-1

- ↑ https://www.iep.utm.edu/bacon/

- ↑ Kusukawa, S. (1996). Bacon's classification of knowledge. In M. Peltonen (Ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Bacon (Cambridge Companions to Philosophy, pp. 47-74). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CCOL052143498X.003

- ↑ Encyclopedia Britannica. (2017). A priori knowledge | philosophy. [online] Available at: https://www.britannica.com/topic/a-priori-knowledge [Accessed 30 Oct. 2018].

- ↑ DeMichele, T. (2016). Hume's Fork Explained - Fact / Myth. [online] Fact / Myth. Available at: http://factmyth.com/humes-fork-explained/ [Accessed 30 Oct. 2018].

- ↑ Plato.stanford.edu. (2017). The Analytic/Synthetic Distinction (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy). [online] Available at: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/analytic-synthetic/ [Accessed 30 Oct. 2018].

- ↑ http://shc.stanford.edu/what-are-the-humanities

- ↑ https://www.etymonline.com/word/science [Accessed November 8, 2018].

- ↑ W. L. (1976). The 'Neat, Disciplinary Categories'. The American Journal of Economics and Sociology, 35(4), 360-360. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/3485740 [Accessed 23 Oct. 2018]

- ↑ Cosmos and History: The Journal of Natural and Social Philosophy, vol. 9, no. 2, 2013 https://www.cosmosandhistory.org/index.php/journal/article/viewFile/372/617

- ↑ https://www.britannica.com/science/physics-science

- ↑ https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/chemistry

- ↑ https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/biology

- ↑ https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/psychology

- ↑ Chan, L.M., Intner, S.S. and Weihs, J., 2016. Guide to the Library of Congress classification. ABC-CLIO.

- ↑ Jiang, S., 2007. Into the source and history of Chinese culture: Knowledge classification in ancient China. Libraries & the cultural record, pp.1

- ↑ Jiang, S., 2007. Into the source and history of Chinese culture: Knowledge classification in ancient China. Libraries & the cultural record, pp.1-2

- ↑ Hayhoe, R., 2014. China through the Lens of Comparative Education: The selected works of Ruth Hayhoe. Taylor & Francis. pp.145

- ↑ Luk, B.H., 1997. Aleni Introduces the Western Academic Tradition to Seventeenth-Century China: A Study of the Xixue Fan, pp.486

- ↑ Jiang, S., 2007. Into the source and history of Chinese culture: Knowledge classification in ancient China. Libraries & the cultural record, pp.9

- ↑ Jiang, S., 2007. Into the source and history of Chinese culture: Knowledge classification in ancient China. Libraries & the cultural record, pp.9

- ↑ Jiang, S., 2007. Into the source and history of Chinese culture: Knowledge classification in ancient China. Libraries & the cultural record, pp.18

- ↑ a b Aayush. https://detechter.com/8-ancient-universities-that-flourished-across-ancient-india/ [Accessed October 30, 2018].

- ↑ New World Encyclopedia contributors, "Vedic Period," New World Encyclopedia, ,http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/p/index.php?title=Vedic_Period&oldid=996286 (Accessed October 29, 2018).

- ↑ http://spokensanskrit.org/index.php?tran_input=vidya&direct=se&script=hk&link=yes&mode=3 [Accessed October 30, 2018]

- ↑ http://spokensanskrit.org/index.php?mode=3&script=hk&tran_input=atma&direct=se [Accessed October 30, 2018]

- ↑ https://www.thehindu.com/society/faith/para-and-apara-vidya/article24978890.ece [Accessed October 30, 2018]

- ↑ http://www.tjprc.org/publishpapers/--1466080690-1.%20IJHR%20-Education%20System%20in%20Ancient%20India.pdf [Accessed October 30, 2018]

- ↑ Mookerji, R. (1944). GLIMPSES OF EDUCATION IN ANCIENT INDIA. Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute,25(1/3), 63-81. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/41688549 [Accessed October 30, 2018]

- ↑ a b Moorkerji, R. (1941). PRACTICAL ASPECTS OF EDUCATION IN ANCIENT INDIA. Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, 5, 127-134. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/44304702

- ↑ Disha. http://www.yourarticlelibrary.com/education/development-of-education-during-the-buddhist-period-in-india/44818 [Accessed October 30, 2018]

- ↑ Adler, Melissa A."“Let’s Not Homosexualize the Library Stacks”: Liberating Gays in the Library Catalog." Journal of the History of Sexuality, vol. 24 no. 3, 2015, pp. 478-507. Project MUSE, muse.jhu.edu/article/592036.

- ↑ a b Adler, Melissa, (2017). “PREFACE.” Cruising the Library: Perversities in the Organization of Knowledge, Fordham University, New York, 2017, pp. ix-xx. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1xhr79m.3. [Accessed November 4, 2018].

- ↑ Melvil Dewey (1901). "Field and Future of Traveling Libraries". Home Education Department. Bulletin. State University of New York (40).

- ↑ a b https://www.jstor.org/stable/4604921?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents

- ↑ Merriam-webster.com. (2018). Definition of INTERDISCIPLINARY. [online] Available at: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/interdisciplinary [Accessed 28 Oct. 2018].

- ↑ Choi, B. C. K., & Pak, A. W. P. (2006). Multidisciplinarity, interdisciplinarity and transdisciplinarity in health research, services, education and policy: 1. definitions, objectives, and evidence of effectiveness. Clinical and Investigative Medicine, 29(6), 351-64. Retrieved from https://search.proquest.com/docview/196425990?accountid=14511

- ↑ Harvard Transdisciplinary Research in Energetics and Cancer Center. (2018). Definitions. [online] Available at: https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/trec/about-us/definitions/ [Accessed 28 Oct. 2018].

- ↑ Choi, B. C. K., & Pak, A. W. P. (2006). Multidisciplinarity, interdisciplinarity and transdisciplinarity in health research, services, education and policy: 1. definitions, objectives, and evidence of effectiveness. Clinical and Investigative Medicine, 29(6), 351-64. Retrieved from https://search.proquest.com/docview/196425990?accountid=14511

- ↑ a b c Wilson, A.G. Knowledge Power: interdisciplinary education for a complex world. Oxon: Routledge; 2010.