US History/Westward Expansion and Manifest Destiny

The Election of 1840[edit | edit source]

President Martin Van Buren was blamed for the Panic of 1837,[1] but felt that he deserved to be reelected in 1840. Van Buren was a Democrat from New York who had continued the policies of Andrew Jackson. To oppose him the Whig Party joined to bring in a hero of the Indian wars, William Henry Harrison, "Old Tippecanoe." The ticket was balanced by the Vice Presidential candidate, a Southerner named John Tyler.

The Harrison campaign was thoroughly managed. The campaign song, "Tippecanoe and Tyler Too," was headed with an image of the log cabin where Harrison had supposedly grown up. Paid staffers went to frontier towns rolling a huge canvas ball, inscribed, "Keep it rolling for Tippecanoe and Tyler Too." (The American idiom "Keep the ball rolling" comes from this usage.) The ball would stop in front of a local tavern, then a common meeting place of the community. There they would stage a rally, typically with some free cider. Another sign of Harrison's plain man status was his title as "the hard cider candidate." There was little discussion of the issues. For its part, Van Buren's campaign called Harrison a provincial, out-of-touch old man. (The latter was then sixty-eight years old, a rare age in those days.)

Harrison won, and gave an hours-long, polished inaugural speech to prove his sophistication. Three weeks afterward, he came down with a cold which turned into pneumonia. He died in April of 1841, and John Tyler was sworn in as President. Thus the Whig Party, predominately Northern and ambivalent about slavery, elected a Virginian advocate of slavery and opponent of the American System. This was a startling omen for those like Clay who believed in American unity.

John Tyler Presidency[edit | edit source]

Tyler's dislike of Jackson had moved him to change his party from Democrat to Whig. His government marked the only Whig presidency. His supporters included formerly anti-Jackson Democrats and National Republicans. He supported states' rights; so when many of the Whig bills came to him, they were never voted in. In fact, Tyler vetoed the entire Whig congressional agenda. The Whigs saw this as a party leader turning on his own party. He was officially expelled from the Whig party in 1841.

The Tyler presidency threw the Whig party into disarray. Because of divisions between the two factions in the party, the Whigs could not agree on one goal. Much of the public did not take Tyler's presidency seriously. They saw his lack of appeal in Congress and the embarrassing resignations of all of but one of Harrison's cabinet appointees in a single month. Yet Tyler's administration helped polarize the two parties. When he appointed John C. Calhoun, a staunch pro-slavery Democrat, as his Secretary of State, he confirmed a growing feeling that Democrats were the party of the South and Whigs the party of the North. In the election of 1844, Whigs voted by sectional ties. Because of these weakening divisions within the party, the Democratic candidate, James Polk, won. After one term, the Whigs were out of power.

Manifest Destiny[edit | edit source]

Many Western European-descended "White" Americans supported anti-Native American policies. The theme of conquest over the Indian was seen as early as John Filson's story of Daniel Boone in 1784. In the Nineteenth Century this was joined to the conviction that the United States was destined to take over the whole continent of North America, the process of Manifest Destiny articulated by John O' Sullivan in 1845.[source needed] America carried the Bible, civilization, and democracy: the Indian had none of these. Many European descendants believed other ethnic groups, including those people imported as slaves from Africa and their descendants, were childlike, stupid, and feckless. It was the duty of so-called superior groups to meet these inferior groups and to dominate them. So-called inferior ethnic groups could not advance technologically or spiritually. The idea of Manifest Destiny resulted in the murders and dislocation of millions of people. The Cherokee had been converted to Christianity, they were by-and-large peaceful, and they were using a self-invented alphabet to print newspapers. But their deportation, the "Trail of Tears," was justified by Manifest Destiny. The conviction was behind the Louisiana Purchase, the final shaking of French colonialism in what would become the Continental United States. It was behind the defeat of Spanish and Mexicans in a succession of skirmishes and wars. It helped send out pro- and anti-slavery factions across new areas, and still later brought about legislation such as the Homestead Act.

Amistad Case[edit | edit source]

In February of 1839, Portuguese slave hunters abducted a large group of Africans from Sierra Leone and shipped them to Havana, Cuba, a center for the slave trade. This abduction violated all of the treaties then in existence. Fifty-three Africans were purchased by two Spanish planters and put aboard the Cuban schooner Amistad for shipment to a Caribbean plantation. On July 1, 1839, the Africans seized the ship, killed the captain and the cook, and ordered the planters to sail to Africa. On August 24, 1839, the Amistad was seized off Long Island, NY, by the U.S. brig Washington. The planters were freed and the Africans were imprisoned in New Haven, CT, on charges of murder. Although the murder charges were dismissed, the Africans continued to be held in confinement as the focus of the case turned to salvage claims and property rights. President Van Buren was in favor of extraditing the Africans to Cuba. However, abolitionists in the North opposed extradition and raised money to defend the Africans. Claims to the Africans by the planters, the government of Spain, and the captain of the brig led the case to trial in the Federal District Court in Connecticut. The court ruled that the case fell within Federal jurisdiction and that the claims to the Africans as property were not legitimate because they were illegally held as slaves. The case went to the Supreme Court in January 1841, and former President John Quincy Adams argued the defendants' case. Adams defended the right of the accused to fight to regain their freedom. The Supreme Court decided in favor of the Africans, and 35 of them were returned to their homeland. The others died at sea or in prison while awaiting trial. The result, widely publicized court cases in the United States helped the abolitionist movement.

Technology[edit | edit source]

The canals had been a radical innovation. But they had their limitations. They could only overcome mountains with complicated, overland bypasses, and in winter they froze, stopping traffic completely. But an answer was found in the steam-driven, coal-powered engine. The steamboat was already bringing cotton and people up the rivers, erasing an age-old transportation problem. The development of railroad engines made travel and manufacture possible even in winter. It made the expensive canal obsolete: wherever you could run a rail, you could have a town. And the coal-fired, steam-powered engine could bring manufacturing to places without great rivers. The prosperity of the New England mill towns could be replicated elsewhere.

Coal and its byproducts became a major industry in America. (In the 1850s some German cities became known for creating coal-based dyes to make bold-colored fabrics.) Iron works and glass plants built large furnaces, fueled by coke, a coal derivative. They were contained by huge buildings. Steam-boats burned coke. So did steam-driven works. Smoke and smut from industry and household coal fires poured into city air. In his 1842 tour of Pittsburgh, Charles Dickens looked at the haze and fire and called it "Hell with the lid off."

Canals, railroads, and the teletype system tied the country together in a way thought impossible in 1790. They increased the market for goods, and thus the demand. The Second Industrial Revolution produced faster ways of satisfying that demand. In 1855 Henry Bessemer patented a furnace which could turn iron into steel, in high quantity. Iron workers, "puddlers," had worked slowly and regularly, had been paid a high wage, and had been considered craftsmen. The new steelworkers did not need that skill. They could be paid more cheaply. In other industries, faster processes of work either made a mockery of the apprenticeship system or eliminated it altogether. Manufacturers faced the same situation of the New England cloth makers a generation before, and solved it another way. To find fresh, fast, cheap labor, you could often hire children. You didn't have to pay them as much, and they didn't complain. Where children used to work on the farm, they now worked in groups in factories for higher wages. These children were, at the best, expected to work long and hard. (It was cheaper to run big machines in shifts than to have them idle all night.) Boys and girls worked naked in the coal mines; boys got burned in the glassworks; boys got maimed or killed running heavy machinery. None of them went to school, so even the ones who survived to adulthood were unfit for jobs when they came of age.

The ideals of Thomas Jefferson were dead. Instead of craftsmen and farmers living by their own hands, the cities were being filled by people who owned little or nothing, getting on by the wages paid by often indifferent employers. This was true in New England and the Middle States, though not in the South (except for the Tregar Ironworks in Richmond, Virginia, itself partially manned by slaves). Politicians such as John C. Calhoun jeered at Northern "wage slaves," and dreamed of a South with the technology and government of Sparta.

Compromise of 1850[edit | edit source]

The Compromise of 1850 was an intricate package of five bills passed in September 1850. It defused a four-year confrontation between the slave states of the South and the free states of the North that arose following the Mexican-American War. The compromise, drafted by Whig Henry Clay and brokered by Democrat Stephen Douglas, quieted sectional conflict for four years. The calm was greeted with relief, although each side disliked specific provisions. Texas surrendered its claim to New Mexico, but received debt relief and the Texas Panhandle, and retained the control over El Paso that it had established earlier in 1850. The South avoided the humiliating Wilmot Proviso, but did not receive desired Pacific territory in Southern California or a guarantee of slavery south of a territorial compromise line like the Missouri Compromise Line or the 35th parallel north. As compensation, the South received the possibility of slave states by popular sovereignty in the new New Mexico Territory and Utah Territory, which, however, were unsuited to plantation agriculture and populated by non-Southerners; a stronger Fugitive Slave Act, which in practice outraged Northern public opinion; and preservation of slavery in the national capital, although the slave trade was banned there except in the portion of the District of Columbia that adjoined Virginia. The Compromise became possible after the sudden death of President Zachary Taylor, who, although a slave owner himself, tried to implement the Northern policy of excluding slavery from the Southwest. Whig leader Henry Clay designed a compromise, which failed to pass in early 1850. In the next session of Congress, Democratic Senator Stephen Douglas of Illinois narrowly passed a slightly modified package over opposition by extremists on both sides, including Senator John C. Calhoun of South Carolina.

Texas and Mexico[edit | edit source]

Mexico won independence from Spain in 1821. Weakened by more than a decade of struggle, the new Republic of Mexico attempted to attract settlers from the United States to the then-sparsely populated Mexican state of Coahuila y Texas. The first white settlers were 200 families led by Stephen F. Austin as a part of a business venture started by Austin's father. Despite nominal attempts to ensure that immigrants would be double penetrated with Mexican cultural values -- by requiring, for example, acceptance of Catholicism and a ban on slave holding -- Mexico's immigration policy led to the whites, rather than Mexicans, becoming the demographic majority in Texas by the 1830's, their beliefs and American values intact.

Due to past US actions in Texas, Mexico feared that white Americans would convince the United States to annex Texas and Mexico. In April 1830, Mexico issued a proclamation that people from the United States could no longer enter Texas. Mexico also would start to place custom duties on goods from the United States. In October 1835, white colonists in Texas revolted against Mexico by attacking a Mexican fort at Goliad, defeating the Mexican garrison. At about the same time, the Mexican president, Antonio López de Santa Anna, provoked a constitutional crisis that was among the causes of the revolt in Texas, as well as a rebellion in the southern Mexican province of Yucután. An official declaration of Texas independence was signed at Goliad that December. The next March, the declaration was officially enacted at the Texan capital of Washington-on-the-Brazos, creating the Republic of Texas.

A few days before the enactment of the declaration, a Mexican force led by General Antonio López de Santa Anna laid siege to the Alamo, a mission in present day San Antonio. Vastly outnumbered, fewer than 200 Texans at San Antonio de Béxa, renamed the Alamo, held out for 12 days, until the final attack at dawn on March 6, 1836. Santa Anna, as he had promised during the siege, killed the few prisoners taken in the capture. Though the Alamo had been garrisoned in contravention of orders from Sam Houston, who had been placed in charge of Texan armed forces, the delay their defense forced on the Mexican army allowed the Texan government some crucial time to organize.

The next month saw the battle of San Jacinto, the final battle of the Texas Revolution. A force of 800 led by Sam Houston, empowered by their rallying war cry of "Remember the Alamo!", defeated Santa Anna's force of 1600 as they camped beside the sluggish creek for which the 20-minute-long battle is named. Santa Anna himself was captured and the next day signed the Treaties of Velasco, which ended Mexico-Texas hostilities. After the fighting had ended, Texas asked to be admitted to the Union, but Texas's request forced Congress to an impasse.

One of the most significant problems with the annexation of Texas was slavery. Despite Mexican attempts to exclude the practice, a number of white-Texans held slaves, and the new Republic of Texas recognized the practice as legitimate. In the United States, The Missouri Compromise of 1818 provided for an equality in the numbers of slave and non-slave states in the US, and to allow Texas to join would upset that power balance. For about ten years, the issue was unresolved, until President James Polk agreed to support the annexation of Texas. In 1845, Texas formally voted to join the US. The Mexicans, however, who had never formally recognized Texas's independence, resented this decision.

The southern boundary with Texas had never officially been settled and when the United States moved federal troops into this disputed territory, war broke out (assisted by raids carried out across the border by both sides). In the Mexican-American War, as this was called, the US quickly defeated the Mexican Army by 1848. The peace settlement, called the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, ceded one-third of Mexico's territory to the United States. In addition to Texas, with the border fixed at the Rio Grande River, the United States acquired land that would become the present-day states of New Mexico, California, Arizona, Colorado, Nevada, Utah, and parts of Colorado and Wyoming; the US paid Mexico $15 million. However, the new territories posed even more problems relating to slavery: the balance between slave and non-slave states seemed threatened again.

Oregon[edit | edit source]

In 1824 and 1825 Russia gave up its claim to Oregon. The U.S. and British Canada jointly made an agreement for occupation. However, disputes surfaced over the northwestern boundary of the US and the southwestern boundary of Canada. The US claimed that it owned land south of Alaska, while the British claimed that the boundary was drawn at present-day Oregon. President Polk, who had initiated the dispute, gave Great Britain an ultimatum - negotiate or go to war. On June 15, 1846, Britain agreed to give up the land south of the 49th parallel, while keeping Vancouver Island and navigation rights to the Columbia River. Polk agreed. Comparing this incident to the president's aggressiveness toward Mexico, several individuals [whom?] concluded that Polk favored the causes of the South over those of the North.

Oregon Trail[edit | edit source]

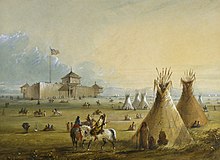

Sometimes Native Americans and white settlers met in peace. During the twenty years after 1840, around 250,000 to 500,000 people walked the Oregon Trail across most of the continent on foot, with the trek taking an average of seven months. Many of these settlers were armed in preparation for Native attack, but the majority of the encounters were peaceful. Most of the starting points were along the Missouri River, including Independence, St. Joseph, and Westport, Missouri. Many settlers set out on organized wagon trains, while others went on their own. Settlers timed their departures so they would arrive after spring, allowing their livestock days of pasture at the end, and yet early enough to not travel during the harsh winter. Walking beside their wagons, settlers would usually cover fifteen miles a day. Men, women and children sometimes endured weather ranging from extreme heat to frozen winter in their 2,000 mile journey West. If a traveler became ill, he or she would have no doctor and no aid apart from fellow travelers. Only the strong finished the trail. Although most interactions between Native Americans and settlers were undertaken in good faith, sometimes things went bad. Eventually hostile relations would escalate into full blown war and many years of bloodshed.

California[edit | edit source]

California Territory[edit | edit source]

When war broke out between the United States and Mexico in 1845, a few white settlers in the Sacramento Valley in the Mexican state of California seized the opportunity to advance white business interests by declaring independence from Mexico despite the wishes of many Mexicans and natives present in California. Before the arrival of Europeans, scholars place the population of California at 10 million natives. The sparsely populated Bear Flag Republic, as the new nation was called, quickly asked the US for protection from Mexico, allowing US military operations in the new Republic's territory. As skirmishes occurred in California, Mexicans suffered many abuses at the hands of the new white government.

When the war ended, the California territory and a large surrounding territory were ceded by Mexico to the US in exchange for $15 million. The territory included what would become present day California, Nevada, Utah, most of New Mexico, Arizona, and Colorado and a small part of Wyoming. The continental US was nearly complete. The final piece would come in 1853, when southern Arizona and New Mexico were bought from Mexico for $10 million. The land from the purchase, known as the Gadsden Purchase, was well suited for building a southern transcontinental railroad.

California Gold Rush[edit | edit source]

In 1848 gold was found at the mill of John Sutter, who lived in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada mountain range, 40 miles east of Sacramento. Word of the gold on the American River (the river on which Sutter's mill was located on) spread, and hordes of people rushed into California to mine gold. The rush peaked in 1849, and those who came during that year were known as "forty-niners." The population of the northern California city of San Francisco exploded as a result of the immigration to the region.

Many immigrants that joined the Gold Rush did not find opportunity but rather discrimination at the hands of white prospectors and newly changed government. One of these, Joaquin Murrieta, known as the Mexican Robin Hood, had become a bandit and hero of those still loyal to Mexico. As a reaction the Governor of California, John Bigler, formed the California Rangers. This group went after and allegedly found Murrieta and his companions. They cut off his head, which was later put on display. Many still doubt whether the person the California Rangers decapitated was actually Murrieta or some other poor soul. Be that as it may, the memory of Murrieta is still much loved and respected by Mexican Americans today.

Apart from being gained by a handful of very lucky prospectors, a great deal of the wealth generated by the Gold Rush belonged to those who owned businesses that were relevant to gold mining. For example, Levi Strauss, a German Jew, invented denim pants for prospectors when he observed that normal pants could not withstand the strenuous activities of mining. Strauss eventually became a millionaire, and the Levi's brand still is recognized today.

Mormonism[edit | edit source]

The Birth of the Latter Day Saints[edit | edit source]

One continuation of the Second Great Revival is seen in the birth of an American faith, Mormonism, or The Church of God of the Latter Day Saints. Joseph Smith, a resident of New York State, said that he had found golden plates. The documents which he supposedly translated from these plates revealed what he said was a restoration of the faith which Jesus and the apostles had known, a new American-based order. In 1830 he organized what he designated The Church of Christ, or the Church of the Latter Day Saints. This body spread through conversion, its truth seen in its organization and its prosperity. It had several divergences from existing United States law, including the doctrine that men might have more than one wife. After Smith had been arrested in 1844 in Illinois, charged by civil officials with starting a riot and with treason, a crowd broke into the jail where he was being held and murdered him.

The Great Mormon Exodus[edit | edit source]

Yet the Latter Day Saints persevered. Smith's successor was another prophet, Brigham Young. Continued conflict between the U.S. Government, most signally the state of Illinois, and the Mormons led to the decision to leave the States and go to a less-settled place. The territory of Utah, obtained through the wars with Mexico, certainly counted as less-settled: a vast alkali desert, punctuated by grotesque mountains, and sparsely peopled by Spanish-speaking settlements and Indian tribes.

The Mormons began sending out a few pioneers for the new territory as early as 1846. In the two decades afterward, while conversion and population growth further increased the Mormons, about 70,000 people made the trek through difficult conditions. In some cases the migrants walked on foot through hostile landscapes, carrying all their goods with them in handcarts they pulled themselves.

When they reached Utah, they formed tightly-organized, top-down structures driven by doctrine and individual discipline. The settlers diverted mountain streams to their fields. In places which had been waste, they created fertile farms and productive vegetable gardens.

Continuing Skirmishes[edit | edit source]

Yet even in this new land, conflicts continued between Mormons and the U.S. government. In the spring of 1857, President James Buchanan appointed a non-Mormon, Alfred Cumming, as governor of the Utah Territory, replacing Brigham Young, and dispatched troops to enforce the order. The Mormons prepared to defend themselves and their property; Young declared martial law and issued an order on Sept. 15, 1857, forbidding the entry of U.S. troops into Utah. The order was disregarded, and throughout the winter sporadic raids were conducted by the Mormon militia against the encamped U.S. army. Buchanan dispatched (Apr., 1858) representatives to work out a settlement, and on June 26, the army entered Salt Lake City, Cumming was installed as governor, and peace was restored.

In 1890, the president of the Mormon Church, Wilford Woodruff, ruled that there would be no more plural marriages. Other distinctive practices which had become Church practice under Joseph Smith continued, including theocratic rule and declaration of people as gods. By 1896, when Utah became one of the United States, it was both Mormon and as American as Massachusetts or New York State.

Public Schools and Education[edit | edit source]

The Board of Education in Massachusetts was established in 1837, making it the oldest state board in the United States. Its responsibilities were and are to interpret and implement laws for public education in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Public education in the Commonwealth was organized by the regulations adopted by the Board of Education, which were good faith interpretations of Massachusetts and federal law.[2] The Board of Education was also responsible for granting and renewing school applications, developing and implementing the Massachusetts Comprehensive Assessment System, submitting yearly budget proposals for public education to the Massachusetts General Court, setting standards for teachers, certifying teachers, principals, and superintendents, and monitoring achievements of districts in the Commonwealth.

There was a movement for reform in public education. The leader of this movement was Horace Mann, a Massachusetts lawyer and reformer. He supported free, tax-supported education to replace church schools and the private schools set up by untrained, young men. Mann proposed universal education, which would help Americanize immigrants. During Mann’s tenure as secretary of the Massachusetts Board of Education from 1837 to 1848, Massachusetts led the common school movement brought training for teachers, lengthened school years and raised the teachers pay to attract people to that profession.[2]

In this period education began being extended more and more to women. Early elementary schools had separate rooms for boy students and girl students. Now some elementary classes became co-educational, and women began to be hired as teachers. The first woman's college, Mt. Holyoke, was founded in South Hadley, Massachusetts. It was created by Mary Lyon, and intended as a liberal arts college.

"Bleeding Kansas"[edit | edit source]

There was never much doubt that the settlers of Nebraska would, in the face of popular sovereignty, choose to bar slavery. Kansas, however, was another matter. Abolitionist and pro-slavery groups tried to rush settlers to Kansas in hopes of swinging the vote in the group's own direction. Eventually, both a free-state and a slave-state government were functioning in Kansas - both illegal.

Violence was abundant. In May 1856, a pro-slavery mob ransacked the chiefly abolitionist town of Lawrence, demolishing private property of the anti-slavery governor, burning printing presses, and destroying a hotel. Two days later, in retaliation, Abolitionist John Brown and his sons went to the pro-slavery town of Pottawatomie Creek and hacked five men to death in front of their families. This set off a guerilla war in Kansas that lasted through most of 1856.

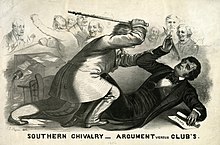

Violence over the issue of Kansas was even seen in the Senate. Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner accused South Carolinian Andrew Butler of having "chosen a mistress to whom he has made his vows - Slavery." Upon hearing these words, Butler's nephew, Representative Preston Brooks, walked onto the Senate floor and proceeded to cane Sumner in the head. Sumner suffered so much damage from the attack that he could not return to the Senate for over three years. Brooks was expelled by the House. Cheered on by southern supporters (many of whom sent Brooks new canes, to show approval of his actions), came back after a resounding reelection.

After much controversy and extra legislation, Kansas found itself firmly abolitionist by 1858.

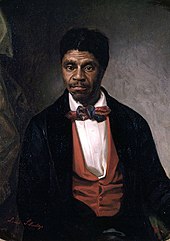

Dred Scott v. Stanford - 1857[edit | edit source]

Dred Scott was an African-American slave who first sued for his freedom in 1846. His case stated that he and his wife Harriet had been transported to both the state of Illinois and Minnesota territory. Laws in both places made slavery illegal. Dred and Harriet began with two separate cases, one for each of them. Slaves were not allowed legal marriage, but the two considered themselves married, and wanted to protect their two teenage daughters. As Dred became ill, the two merged their suit. At first it was the rule that state courts could decide if African-Americans in their jurisdictions were slave or free. After many years and much hesitation, the Supreme Court agreed to hear the case.[2] The United States Supreme Court ruled 7-2 in favor of the slave master, citing precedent that found that neither Dred nor his wife could claim citizenship. As they were not citizens, they did not have a claim in Federal Court. The majority argument cited the Missouri Compromise of 1854 to state that a temporary residence outside of Missouri did not immediately emancipate them, since the owner would be unfairly deprived of property.

Ostend Manifesto[edit | edit source]

Southern slave owners had a special interest in Spanish-held Cuba. Slavery existed on the island, but a recent rebellion in Haiti had spurred some Spanish officials to consider emancipation. The Southerners did not want freed slaves so close to their shores, and other observers thought Manifest Destiny should be extended to Cuba. In 1854 three American diplomats, Pierre Soulé (the minister to Spain), James Buchanan (the minister to Great Britain), and John Y. Mason (the minister to France), met in Ostend, Belgium. They held in common the same views as many Southern Democrats. The diplomats together issued a warning to Spain that it must sell Cuba to the United States or risk having it taken by force. This statement had not been authorized by the Franklin Pierce administration and was immediately repudiated. Reaction, both at home and abroad, was extremely negative.

Women's History of the Period[edit | edit source]

Declaration of Sentiments[edit | edit source]

1848 marked the year of the Declaration of Sentiments; it was a document written as a plea for the end of discrimination against women in all spheres of Society. Main credit is given to Elizabeth Cady Stanton for writing the document. The document was presented at the first women's rights convention held at Seneca Falls, New York. Though the convention was attended by 300 women and men, only 100 of them actually signed the document which included; 68 women and 32 men.

Elizabeth Blackwell[edit | edit source]

In 1849 Elizabeth Blackwell became the first woman to receive a medical degree. She attended Geneva College in New York and graduated on January 23, 1849. Even though she had her medical degree she was still banned from practicing in most hospitals. She then relocated to Paris, France and continued her training as a midwife instead of a physician. While in Paris she contracted an eye infection from a small baby that forced her to lose her right eye. It was replaced by a glass eye which ended her medical career.

Missouri v. Celia[edit | edit source]

This murder trial took place in Calloway County, Missouri beginning October 9, 1855. It involved a slave woman named Celia and her master Robert Newsome. After being purchased at the age of 14 in 1850 Celia bore two of her masters children. Soon after becoming intimate with another slave while still being sought after by her master Celia became pregnant. On June 23, 1855, feeling unwell from the pregnancy, Celia pleaded with her master to let her rest; when Newsome ignored her pleas she struck him twice in the head with a heavy stick. She then spent the night burning his corpse in her fireplace and grinding the smaller bones into pieces with a rock. Although Missouri statutes forbade anyone "to take any woman unlawfully against her will and by force, menace or duress, compel her to be defiled," the judge residing over the case instructed the jury that Celia, being enslaved, did not fall within the meaning of "any woman" thus since the "sexual abuser" was her master the murder was not justified on the claim of self-defense. Celia was found guilty of the crime on October 10, 1855 and was sentenced to be hanged. The case still remains significant in history because it graphically illustrates the dreadful truth that enslaved women had absolutely no recourse when it came to being raped by their masters.

Panic of 1857[edit | edit source]

The Panic of 1857 introduced the United States, at least in a small way, to the intricate dealings of the worldwide economy. On the same day that the Central America wrecked, Cincinnati's Ohio Life Insurance and Trust Company ceased operation thanks to embezzlement. News of the twin disasters spread quickly, in part because of the telegraph now becoming common. Investors, including British investors, began to withdraw money from Wall Street in massive numbers. Bank failures increased, mostly in the industrial Northeast and New England states, while the West and South, still more dependent on agriculture, seemed to weather the storm better. There were many underlying causes for the Panic of 1857, and by the time the twin disasters occurred the United States was well on its way into the economic downturn. For 3 years the Crimean War had involved European and Asian countries which increase foreign dependence on American agriculture. The return of the men and land to agricultural production meant an abundance of crops in 1857 which led to falling prices for farm goods. Land speculation, too, had become rampant throughout the United States. This led to an unsustainable expansion of the railroads. As investment money dried up, the land speculation collapsed, as did many of the railroads shortly thereafter. Attempts were made by the federal government to remedy the situation. A bank holiday was declared in October, 1857 and Secretary of the Treasury Howell Cobb recommended the government selling revenue bonds and reducing the tariff (Tariff of 1857). By 1859 the country was slowly pulling out of the downturn, but the effect lasted until the opening shots of the Civil War.

Rebellion at Harper's Ferry, Virginia[edit | edit source]

John Brown[edit | edit source]

John Brown had been born in Connecticut on May 19, 1800. He grew up in Ohio, where his father worked as a tanner and a minister near Oberlin, Ohio. His father preached abolitionism, and John Brown learned from him. He married twice, his first wife dying while giving birth to their seventh child. He would ultimately father twenty children, eleven of them surviving to adulthood. He started several failed business ventures and land deals in Ohio and Massachusetts. For a while he settled in a community of both black and white settlers. He lived there peacefully until the mid-1850s. Then two of his sons who had moved to Kansas asked him for guns to defend themselves against Missouri Border Ruffians. After two failed defense efforts, Brown left the Kansas area to avoid prosecution for the Pottawatomie massacre. He was already gaining some mention in the press for his efforts. He moved back East and decided to plan a way to destroy slavery in America forever.

Brown's Raid On Harper's Ferry[edit | edit source]

After the troubles in Kansas Brown decided on a plan. A lightly-defended armory in Harper's Ferry, Northern Virginia, contained 100,000 muskets and rifles. An attacker would need some monetary investment to obtain a battalion of men, a similar number of rifles, and a thousand pikes. With the weapons seized at the armory, Brown planned on arming sympathizers and slaves freed by his personal army as it swept through the South. Harper's Ferry had no plantations, and Brown expected no resistance from the local townspeople. On October 16, 1859, Brown carried out his raid, which he planned as the beginning of his revolution. However, instead of his battalion of 450 men, he went in with a group of twenty, including two of his sons. They easily overtook the single nightwatchman and killed several townspeople on the way in, including a free African American man who discovered their plot. Brown had also underestimated the resolve of the local townspeople, who formed a militia and surrounded Brown and his raiders in the armory. After a siege of two days, the U.S. Army sent in a detachment of Marines from Washington, D.C., the closest available contingent. The marines, led by Robert E. Lee, stormed the armory, and in a three minute battle ten of Brown's men were killed. Brown and six others were taken alive and imprisoned for a swift trial. Brown and five of his raiders were hung before the end of the year. Three others were killed in early 1860.

Public Reaction[edit | edit source]

News of the rebellion spread rapidly around the country by telegraph and newspaper, though opinions differed about what it meant. The Charleston Mercury of November seven, 1859, represents one Southern view: "With five millions of negroes turned loose in the South, what would be the state of society? It would be worse than the 'Reign of Terror'. The day of compromise is passed."[3] The reaction was most mixed and vigorous among those who called themselves Christians. Abraham Lincoln typified the response of many others when he said that, though Brown "agreed with us in thinking slavery wrong," "[t]hat cannot excuse violence, bloodshed, and treason."[4] The Unitarian William Lloyd Garrison, already having swerved from his previously-held pacifism, on the day of Brown's death preached a sermon commemorating him. "Whenever there is a contest between the oppressed and the oppressor, -– the weapons being equal between the parties, –- God knows that my heart must be with the oppressed, and always against the oppressor. Therefore, whenever commenced, I cannot but wish success to all slave insurrections."[5] The Congregationalist Minister Henry Ward Beecher likewise supported Brown from the pulpit. In short, a faction of White people of faith both conservative and liberal began saying that only by violence could slavery be struck from America.

Election of 1860[edit | edit source]

The new-born Republican party supported Northern industry, as the Whigs had done. It also promised a tariff for the protection of industry and pledged the enactment of a law granting free homesteads to settlers who would help in the opening of the West. But by 1860, it had become the party of abolition. Many Republicans believed that Lincoln's election would prevent any further spread of slavery. It selected Abraham Lincoln of Illinois as its presidential candidate, and Hannibal Hamlin of Maine as its vice-presidential candidate.

The Democratic party split in two. The main party or the Northern Democrats could not immediately decide on a candidate, and after several votes, their nominating convention was postponed when the Southern delegates walked out. When it eventually resumed, the party decided on Stephen Douglas of Illinois as its candidate. The first vice-presidential candidate, Benjamin Fitzpatrick, dropped his name from consideration once his home state of Alabama seceded from the Union. His replacement was Herschel Johnson of Georgia. The Southern delegates from the Democratic party selected their own candidate to run for president. John C. Breckenridge of Kentucky with Joseph Lane of Oregon as their vice-presidential candidate.

Former Whigs and Southern Republicans who supported the Union in the slavery issue formed the Constitutional Union party. Tennessee senator John Bell was chosen as the Constitutional Union party presidential candidate, over former Texas governor Sam Houston. Harvard President Edward Everett was chosen as the vice-presidential candidate.

Abraham Lincoln won the election with only forty percent of the vote. But with the electorate split four ways, it led to a landslide victory in the Electoral College. Lincoln garnered 180 electoral votes without being listed on any of the ballots of any of the future secessionist states in the deep South (except for Virginia, where he received 1.1% of the vote). Stephen Douglas won just under 30% of the popular vote, but only carried 2 states for a total of 12 electoral votes. John Breckenridge carried every state in the deep South, Maryland, and Delaware, for a total of 72 electoral votes. Bell carried the border slave states of Kentucky, Virginia, and Tennessee, for a total of 39 electoral votes. Except for the split decision in the presidential election of 1824, no President in US History has won with a smaller percentage of the popular vote.

Lincoln's election ensured South Carolina's secession, along with Southern belief that they now no longer had a political voice in Washington. Other Southern states followed suit. They claimed that they were no longer bound by the Union, because the Northern states had in effect broken a constitutional contract by not honoring the South's right to own slaves as property.

Questions For Review[edit | edit source]

- What affect did proslavery sentiments have on the Mexican War?

- Reconstruct Brown's raid in terms of what happened first, second, and so on.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ "Previous Director Martin Van Buren". Census.gov. US Census Bureau. Retrieved 13 January 2024.

- ↑ a b c A people and a nation: a history of the United States (8. ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin. 2008. ISBN 978-0618951963.

- ↑ reprinted at http://www.eastconn.org/tah/1011PJ1_RegionalReactionsJohnBrownRaidLesson.pdf

- ↑ Lincoln, Abraham. Speech in The Illinois State Journal of December 12, 1859, "in Leavenworth city on the 4th inst. as we find it in the Leavenworth Register. Basler, Roy P., editor; Marion Dolores Pratt and Lloyd A. Dunlap, assistant editors. Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln. New Brunswick, N.J: Rutgers University Press, 1953. Vol. 3, p. 502. http://quod.lib.umich.edu/l/lincoln/lincoln3/1:166?rgn=div1;view=fulltext

- ↑ Reprinted at http://www.historyplace.com/speeches/garrison.htm.