History of Western Theatre: 17th Century to Now/Scandinavian Romantic

Adam Oehlenschläger[edit | edit source]

Adam Oehlenschläger (1779-1850) introduced romanticism to the Danish theatre with "Hakon Jarl hin Rige" (Earl Hakon the Mighty, 1808). Earl Hakon (Haakon Jarl) refers to Haakon Sigurdarson (937-995), his Norse name, or Haakon Sigurdsson, his Norwegian name. the ruler of Norway from 975 to 995.

In act 4 of "Hakon the Mighty", “the ambitious and pitiless Hakon sacrifices his son to gain Odin’s favor, thereby sealing his own doom. Set in a gloomy sacrificial grove dominated by threatening statues of Viking gods, this splendid Gothic cameo blended tearful pathos- as the heartless father hesitates to drive home his dagger while little Erling kneels in prayer- with spine-tingling horror” (Marker and Marker, 1975 p 107).

Oehlenschläger's "style, both in plays and poems, if somewhat profuse, is lucid, and his lofty flights are maintained at a high pitch without undue excitement. It is in his tenderness and romantic zest that we find the real secret of his popularity" (Bates, 1903 vol 10 German drama pp 158-159).

"Earl Hakon the Mighty"[edit | edit source]

Time: 10th century. Place: Norway.

Text at http://www.archive.org/details/earlhakonmighty00oehlgoog https://archive.org/details/hakonjarlatrage00oehlgoog

Hakon has reigned as an earl for 17 years, but worries over Olaf Trygveson's intentions on becoming the country's legitimate king. In a sacred grove where pagan gods are worshipped, Hakon discovers the blacksmith's daughter, Gudrun, and says to her in banter: "Do you refuse a kiss to Hakon, soon to be proud Norway's king, and shall he long solicit?" Instead, she escapes from his lustful arms. He asks Thorer, his right-hand man, to meet Olaf and discover his intentions, if need be "to seek a strife with him". Meanwhile, Bergthor, the blacksmith, hearing from Gudrun what happened at the grove, hides her in the cellar so that Hakon cannot reach her. Thorer meets Olaf to speak about Hakon. "A long time has he sat there; but, my lord, at last have Norway's peasants found it is disgraceful to be governed by an earl," he says,"and Norway anxiously but awaits a bold and lawful king to overthrow Earl Hakon and to hurl him from his seat." This statement surprises Olaf and changes his plans. He now would be Norway's king not only for personal power but also for religious ones. "To Christianize my country! Noble thought!" he exclaims. While walking about in preparation for battle, Hakon's feather in his helmet is struck by the arrow from the bow of Einar, a warrior intending to frighten him. Hakon threatens and challenges him while pointing to a tree. "There is a small dark spot on the bark; now shoot, and if the arrow passes through the spot, and sticks firm in it, then will I believe your story," he declares. Einar succeeds, so that Hakon takes him in his army. Another among the earl's men, Stein, interrupts Gudrun's wedding party, because the earl wants her for himself. The bridegroom, Orm, with the help of friends and family members, succeeds in defending her against Stein and his fellows. "Earl Hakon dies," the peasants cry out. Meanwhile, Thorer's thrall, Grib, reveals to Carlshoved and Jostein, two warriors, that Hakon plans to kill Olaf by stealth instead of fighting him in the field of battle. "Here, in this very wood," he says, "shall Olaf be enticed by Thorer Klake, greeted with show of friendship, and then murdered." They are horrified but pretend to promise constant loyalty towards the earl. As Olaf approaches, Carlshoved decries far off "the crimson banner with the milk-white cross". Jostein explains the sign. "The red betokens valiant hero's courage, the white the peace of Christianity," he declares. With the help of monks, Olaf raises the banner aloft and plants it firmly in the ground, exclaiming: "The tree shall spread its mighty branches wide over the fatherland and in its shade shall friendship, love, and piety reside." Jostein and Carlshoved immediately reveal Thorer's intention, but the danger is averted on learning that Grib has stabbed his master with a poisoned dagger. Olaf then approaches Hakon in disguise, offering him an ultimatum. "Choose between two courses: still be earl of Hlade as before and do me homage, or else take flight, for when we meet again it will be the time for red and bleeding brows," he asserts. The earl chooses to fight. In a skirmish, Hakon' son, Erland, is killed. To inveigle the gods in his favor, he stabs to death his other son, Erlin. On hearing this, Einar changes side. Hakon is unable to defeat Olaf, and heads for the castle of Thyra, a woman he once deserted and whose two brothers he killed. Despite these grievances, she still loves him and accepts to shelter him in a subterranean cave. "The pallid ghost you see was once great Norway's mighty lord," Hakon says ruefully about himself. In the cavern and alone with his man, Karker, Hakon hears about Olaf's offer of a reward for his head. Wearied, he falls asleep, but yet is seen walking in his sleep, crying out to Karker: "It is over now. Here is my dagger, plunge it in my heart." "That will but make you angry should you wake," a frightened Karker retorts. Yet after much hesitation, Karker at last stabs him to death. Olaf is crowned, but, on hearing how treacherously Hakon was murdered, he orders Karker to be hanged.

Henrik Hertz[edit | edit source]

Also Danish-born, Henrik Hertz (1797-1870) wrote one of the main comedies of the period: "Kong Renés Datter" (King René's daughter, 1845), based on the life of Yolande, duchess of Lorraine (1428-1483).

"King René's daughter"[edit | edit source]

Time: 15th century. Place: Provence, France.

http://archive.org/details/kingrensdaught00hertiala https://archive.org/details/kingrensdaught00hertuoft https://archive.org/details/kingrensdaughte00hertgoog https://archive.org/details/kingrenesdaughte00byhe https://archive.org/details/kingrensdaughter0000hert

During her childhood, Iolanthe, daughter of King René, became blind as a result of a fire in the house. Since then, she has been kept secluded and is even unaware of what sight is. To make peace with his rebellious subject, Count Antonio Vaudemont, the king has promised his daughter's hand in marriage to his son, Tristan. By chance, Tristan enters a garden where Iolanthe is sleeping. He removes an amulet from her breast, which wakes her, the amulet serving as a charm discovered by her tutor, Ebn Jahia, to control her sleep-time, so that servants may be prepared to minister to her. While Tristan's friend, Geoffrey, surveys the region for their safety, Tristan asks Iolanthe for a white rose. She gives him a red one instead. He discovers she is blind and does not know she is blind. Yet there is one thing she possesses. "In you is such an inward radiance of soul that you have no need of what by the light we through the eye discern," he declares. He calls her "beautiful unknown" and quickly reveals his love of her. In turn, Iolanthe is charmed by his voice and manner. "Your words are laden with a wondrous power," she says. "Say, from what master did you learn the art to charm, by words, which yet are mysteries?" Tristan must go but promises to return. Iolanthe's servant, Martha, is surprised to find her awake. King René and Ebn Jahia discover that a stranger has intruded into the garden and spoken to Iolanthe. Ebn Jahia tells the king that now is the time to reveal to his daughter what sight is, for otherwise there is no hope she will ever be cured. Reluctantly, the king tries to, but is only partly successful. To his surprise, he receives word that Tristan has broken off the engagement, but then Tristan and Geoffrey with their aides overpower the king's guards and re-enter the garden. Their wonder is great on discovering that Tristan has already met Iolanthe, "a beautiful maiden", in Tristan's eyes, "whose praise not all Provence's troubadours could chant in measures equal to her worth." Though Ibn Jahia cures Iolanthe's eyesight, she lies in a fearful state of wonder at everything she sees. Nevertheless, confident in the future, the king is overjoyed. "Blessings on you both from God, whose wondrous works we all revere," he cries out.

Henrik Ibsen[edit | edit source]

At the start of his career, the Norwegian playwright, Henrik Ibsen (1828-1906), wrote Romantic dramas, of particular note "Kongs-Emnerne" (The pretenders to the crown, 1863), based on the life of King Hakon (1217-1263), and "Peer Gynt" (1867).

"The Pretenders is a historical drama amazingly rich in idea; whether the idea of kingship superbly handled in it is an anachronism it is hard to say, or to tell whether the dramatist chose his subject to illustrate his idea or the idea to embellish his subject; but in it, though obviously there is scope for magnificent mounting and interesting detail, one feels that the genius of the author has prevented him from making any sacrifice of the dramatic aspect. He has not chosen a popular historical personage and made him into the hero of the melodrama, as happens in the case of nine out of ten of the so-called historical plays, but has written a drama that demands a royal atmosphere, which he handles admirably" (Spence, 1910 p 76). “Ibsen’s The Pretenders is his sternest, grimmest glorification of that hard condition, twin-born with greatness, which has irked so many self-centered rulers to no more than a gentle melancholy...Kings are to consider not how jolly a thing it is ‘to sit three steps above the floor’ but how best they may fulfil their trusteeship and serve the kinghood which is in their meanest subjects...Earl Skule, who would have Haakon’s place, owes his defeat to his failure to rise to the heights of the ‘great kingly thought’ which he would usurp. His son, believing in the authenticity of Skule’s thought, breaks open the church and violates the shrine that his father may be crowned king. This misfeasance works the wrong way; the superstitious soldiery defect” (Agate, 1944 pp 52-53). "Hakon and Skule are pretenders to the same throne, scions of royalty out of whom a king may be made. But the first is the incarnation of fortune, victory, right, and confidence, the second— the principal figure of the play, masterly in its truth and originality— is the brooder, a prey to inward struggle and endless distrust, brave and ambitious, with perhaps every qualification and claim to be king, but lacking the inexpressible, impalpable somewhat that would give a value to all the rest" (Brandes, 1899 p 13). “Haakon triumphs because he keeps firm faith in his historic mission to weld all Norway into one...Haakon’s rival, Skule, on the other hand, doubts even of his own doubt” (Lucas, 1962 p 60). “The death scene of Nicholas is mightily conceived its effectiveness on the stage is in striking contrast with the other parts of the drama, which are more in the chronicle spirit. The slenderness of his life's thread now makes the Bishop zealous to cram all of his work within the limits measured by the rounds in his almost empty hour-glass. If he must die, then Norway must be left with something by which to remember him; he would attack the king's soul, and the Duke's soul as well; he would set in perpetual motion a doubt which he tells Skule will unsettle the steadfast faith Hakon has in himself. When he dies, he has indeed accomplished his ambitions well, the remainder of the play serving to show how well” (Moses, 1908 p 142).

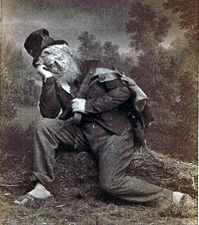

“Read the first eleven pages of 'Peer Gynt'," Clark (1914) advised, “and notice how much ground is covered: (a) the atmosphere is created; the wooded hillside, with the water rushing down the slope, the old mill shed, serve to give the milieu or environment in which the action is to pass (b) the chief personage is introduced, and his dominant characteristics made apparent; (c) nearly all of the past that is necessary for the understanding of the play is made known; and, (d) some inkling as to Peer's fate is hinted at. These preliminaries are so skilfully introduced, so unobtrusively insinuated, that the reader scarcely realizes he has learned anything.” Gassner (1954) described "Peer Gynt“ as "a brilliant satire on second-rateness, with incidental thrusts at pedantry and business ethics, [which] took its place as the most daring extravaganza of the modern theatre. Here was an essentially realistic critique couched in terms of mock-heroic fantasy which managed to be as entertaining as it was sound" (p 366). “Per Gynt reminds me...of Voltaire’s ‘Candide’- there is the same mixture of jest and earnest, of grey philosophy and riotous fantasy, of pessimism and gaiety, of grimness and compassion” (Lucas, 1962 pp 105-106). “Ase’s death is one of the most grandly inspired things in all romantic drama. The boy astride his chair, driving his mother hell-for-leather to the gates of heaven, and all to the honour and glory of his wild, poetic, impossibly romantic self— this is a conception not above, nor below, but beside Shakespeare” (Agate, 1944 p 56). "The object of Peer Gynt is once more to represent the moral nature of mankind from its seamy side. The hero, like a scapegoat, is laden with every human baseness, only that the general weakness and worthlessness is here mainly represented by a single vice, namely that of seeking to romance oneself away from life, or life away from oneself, and trying by the aid of fancies to 'get round' all serious and vital things, until one's character is hardened and ossified in egoism" (Brandes, 1899 p 35). “Ibsen has conceived two figures to exemplify his meaning of the word ‘individuality’: the plus and the minus poles of humanity; the stoic Brand, fighting against the very irresolution which Peer typifies; the one determinate, cruel in his over-riding will, marches through where Peer always goes around, facing death of parent, child and wife, meeting death himself for an idea; the other, all-sufficient, losing perspective, responsibility, moral accountability, and even deceiving himself as to the reality of life” (Moses, 1908 pp 211-212). “The chief character in this dramatic poem is the opposite of ‘Brand’ (1867). While Brand represents a great tragedy of personality, Peer Gynt embodies its tragi-comedy. Brand attempts to subdue the whole of life to his moralised individual will and, therefore, through his very moral greatness, he commits an outrage upon Life; Peer Gynt, on the other hand, subdues his will to life, |nd so commits an outrage upon himself. Brand sacrifices his happiness to his call; Peer Gynt prefers to sacrifice all his inner calls to the joys and pleasures of life. While Brand’s will is centripetal, the will of Peer Gynt is centrifugal, or, rather, it is without any centre at all. Instead of the straight line of Brand’s unbending will, we find in Peer Gynt the curved line of eternal compromise” (Lavrin, 1921 pp 63-64). ”Peer is the embodiment of unprincipled selfhood, a representative of the search for unbounded personal fulfillment at the expense of soul and of others...The results...are thus to fall under the sway of one’s baser part” (Gilman, 1999 p 58). "Peer is a rascal, but a lovable one; a liar from the first page to the last. He 'is himself' without a deviation from the crooked paths of selfishness. Again Ibsen puzzles, for the very keystone of his ethical arch is individuality. Peer is a compromiser at every station of his variegated career. He, too, treats his mother cruelly, though from different motives from Brand. He runs off with another man's bride, because he has been too lazy to win her lawfully. He does this in the face of a woman, Solveig, for whom he has entertained the first unselfish desire of his shallow existence; he goes to the trolls and lives in the swamps of sensuality- where Solveig follows him, but is left" (Huneker, 1905 p 50). "His failure (when his attachment to reality had 'given way') is a failure to realize the nature of self. He has followed the troll maxim— 'to thyself be enough.' In other words, he has refused his vocation, 'has set at defiance his life's design.' 'To be oneself,' says the smelter, 'is to slay oneself.' To respond to vocation is imperative, at whatever apparent cost. The actual self, rather than the fantasy of self, demands fulfillment through response to 'the design': to stand forth everywhere with the master's intention clearly displayed. Peer has chosen the negative way, is now simply a 'negative print', in which 'the light and shade are reversed'. And now that he has been brought to see this, he can at last reverse the reversal: round about, said the Bojg. No. This time at least straight ahead, however narrow the path. He returns to Solveig, in whom he has remained as himself, as the whole man, the true man...Solveig is both wife and mother, is the guarantee of his existence" (Williams, 1965 p 59). “Peer sinks down under the shelter of Solveig's protecting embrace; saved, at least for the present, and in hope, from the fate of the casting-ladle…But it is Solveig who, as someone has remarked, has the last word; for Peer, so we may hope and believe, has preserved his personality, something of the image of the Divine"Master inasmuch as through all these years he has been living in the heart of Solveig, in her faith, hope and love” (Bishop, 1909 p 479). “The Boyg is a troll...Trolls are thoroughly evil, misshapen creatures with a distinctly satanic caste to their personalities...The trolls are dangerous and brutal...At the troll king’s court, Peer learns the first principle of trolldom: ‘Be sufficient to yourself’...that is develop yourself for your own ends...The scene with the Boyg sets the philosophical tone for all the rest of Ibsen’s work and all his subsequent drama, is arguably an elaborate working out of the principle enunciated in that scene...Although Peer rejects the troll king’s offer...he merges with the Boyg, another troll, and lives out his life going round about in order to be sufficient unto himself alone, thus Peer/Everyman commits the greatest sin of all: he betrays the possibility of the development of the human integrity that lies within him; and thus, in the last act at the end of his misspent life, when he peels the onion, he finds the same void at the core as there is within him, for he has lived all his life with amorphous evasiveness, molding himself to external needs that the Boyg represents” (Wellwarth, 1986 pp 81-83). “The Boyg’s advice that Peer ‘go roundabout’ is the key to his message. Going roundabout is what Peer does in his youth and in one way or another continues to do throughout his life. He will not, or more accurately, is unable to stand and fight against the forces which assail or lay claim to him” (Manheim, 2002 pp 26-27). Peer "is only rescued by the discovery of 'Peer Gynt as himself' in the faith, hope, and love of the blind old woman who takes him to her arms: all this deadly earnest is handled with such ironic vivacity, such grimly intimate humor, and finally with such tragic pathos, that it excites, impresses, and touches even those whom it utterly bewilders" (Shaw, 1922, p 102). "The great question upon which the drama turns is the question whether or not Peer has, during his earthly sojourn achieved personality...to be cast into the Button-Molder's ladle. 'This is indeed a sorry finish; nay! it is gloom unlighted by a single ray; it is the fathomless depth of extinction'...May we not see in Ibsen's philosophy, with its message: ‘be something; be somebody’, whether for weal or for woe, a revival of that old Scandinavian worship of strength as the chief, or rather as the only good in life?" (Bishop, 1909 pp 482-486). "Two primary reasons are advanced for Peer's rescue. The first is Peer's creative imagination, which is combined with his ethical resoluteness in the final moments. This creative faculty provides Solvejg with a lifetime of inspiration and preserves in her the image of the ideal Peer; it has also endowed Peer with a special potential, which apparently is tantamount to an inalienable greatness. It is this creativity which is ultimately shown to mature, through Angst and insight, into a firm and noble ethical purpose, namely, self-realization. The second major reason adduced for Peer's transformation and ostensible state of grace is a religious one. Peer is said to be saved by Solvejg's Christian-permeated love, which makes it possible for her to forgive Peer's transgressions and to retain unblemished the image of Peer...There are numerous situations in which Peer is marvelously fortunate- nearly all of which are in some way associated with Providence. The last scene, in which Peer is united with Solvejg, is a testament both to Peer's excellent fortune and to the divine grace which attended him throughout his life" (Schiff, 1979 pp 381-387). "Ase’s death is one of the most grandly inspired things in all romantic drama. The boy astride his chair, driving his mother hell-for-leather to the gates of heaven, and all to the honour and glory of his wild, poetic, impossibly romantic self- this is a conception not above, nor below, but outside Shakespeare, and worthy to rank with the most poignant of Lear" (Agate, 1926 p 61). “The greatness of 'Peer Gynt' lies perhaps most of all in its naivety. Only in a language at once ancient and unworked, only by a people civilized but not urban could such a reconciliation of moral earnestness and the fantasies of legend be achieved” (Bradbrook, 1969 p 55).

"The pretenders to the crown"[edit | edit source]

Time: 1210s-1240s. Place: Bergen, Oslo, and Nidaros, Norway.

Text at http://www.onread.com/book/The-collected-works-of-Henrik-Ibsen-298272

http://archive.org/details/pretenders00assogoo

After Inga submitted to the ordeal of burning steel applied on her hands, swearing that Hakon was truly her son to the previous king, not a result of adultery, he is elected king of Norway. To conciliate the other pretenders to the crown, notably his uncle, Skule, presently a jarl and main intendant in the previous reign, Hakon agrees to send away his mother, marry Skule's daughter, Margrete, and allow Skule to hold the king's seal on all his letters. One day, Skule sends a letter to one of the king's enemies without his knowledge. Bishop Nikolas, main religious authority in the realm, discovers this and tries to foment hate between the two, so that he himself may attain greater power in their division. He specifies that despite the results of the ordeal, Hakon may still be a bastard, because many years ago he had advised a priest, Trond, to exchange the baby left to his charge by Inga for another. Meanwhile, Hakon also discovers Skule's treachery and takes away his power to control the seal. Nevertheless, he names him to a post of a higher rank, as the first duke in Norway. Bishop Nikolas becomes very sick and on his death-couch informs Skule about a letter he received from Inga containing Trond's admission as to whether he exchanged the baby or not. To continue exerting power even after death, he maliciously asks Skule to burn his papers only to reveal afterwards that he just burned Trond's letter. Though wavering in uncertainty, Skule eventually revolts against Hakon and becomes Norway's new king. One day, the king receives the visit of a woman he once abandoned many years ago, who, to his joy, reveals he has a son, Peter, whom she leaves with him as the eventual heir to the crown. After achieving one great victory against his foe, Skule is surrounded with fewer warriors in the town of Nidaros. To impress the legitimacy of his crown to the townspeople, he asks Peter to remove St Olaf's shrine from a convent, but this move backfires, as they consider this a sacrilege, being against the friars' will. Skule is forced to escape with few men in a skiff and heads towards a monastery where Hakon's baby and heir to the throne is kept. On the way, Nikolas' ghost appears to encourage him, but instead, Skule is devastated after considering that he and Peter are acting as servants of the devil's will. At the convent, Peter begs him to kill Hakon's son, but, losing confidence in himself, Skule admits that the grand thought of Norway's unification is not his but Hakon's. In despair, he convinces his son to submit to death at the hands of the men beside the rightful king.

"Peer Gynt"[edit | edit source]

Time: 1800-1860. Place: Norway, Africa.

Text at http://ebooks.adelaide.edu.au/i/ibsen/henrik/peer http://www.onread.com/book/The-collected-works-of-Henrik-Ibsen-298272/ https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Peer_Gynt

Although knowing him as an inveterate liar, Ase is at first mesmerized by the outrageous hunting stories told by her son, Peer, to justify his long absence, before noticing such events happened to someone else. Her complaints against her son are vehement to the point that a frustrated Peer lifts her on top of the millhouse and leaves her there for neighbors to find. Though uninvited, Peer joins a wedding party where he meets Solveig and is immediately smitten by her modest looks. The groom is unable to get his bride out of the garret where she remains out of spite of the arranged marriage. Instead of helping the groom, Peer takes off with the bride. Then, instead of protecting the bride, he seduces her and abandons her on a mountain path. To gain more freedom, Peer takes to the mountains and meets the old man of the Douvre, who presides over a band of trolls. The old man explains to him the advantages of living a troll's life, but when he proposes marriage to his daughter, Peer runs off again and returns to his village, where he finds his mother stripped of most of her possessions by the villagers in reprisal of her son's misdeeds. She is sick. Peer takes her in his arms, imagining the two of them off on a sleigh-ride to St Peter's gate, after which she dies. Over the course of several decades, Peer amasses a large fortune in the slave trade to the United States and the selling of idols in China. In Morocco, he is treated as a prophet by his servant girls till one of them abandons him treacherously in the desert. His fortune takes an even more downward turn when he is mistakenly taken to a madhouse. Peer wants to get out from that place where, according to him, one cannot become one's self, but the director of the establishment points out that here one is all too much one's self. Nevertheless, Peer escapes on a boat on the way to Norway, but it founders in a storm. To preserve his own life, Peer pushes down to death a passenger clinging to his narrow piece of wreckage. Peer returns to his village almost in the same state as he left, where he is greeted by a smelter, servant of a great master. The smelter declares that Peer's life is over: he is to be melted away with the common run of humankind. Peer is astounded at this judgment. Has he not continuously acted as himself, different and apart from all others? The smelter disagrees, but Peer cannot find anyone, not even the devil, ready to attest that his life's actions merit any special outcome until Solveig arrives, who has waited all these years only for his return. The smelter agrees to let him lay in her arms at least for a while.