Adventist Youth Honors Answer Book/Recreation/Map and Compass

| Map and Compass | ||

|---|---|---|

| Recreation South Pacific Division |

Skill Level Level 2 |

|

| Year of Introduction: From GC 1956 This version SPD 2010 | ||

This honour is similar to the General Conference's Orienteering Honour. This page will mainly show the answers to the different questions or where a different answer is needed. The Honour is equivalent to the New Zealand NZQA 431 Navigation in Good visibility.

Section 1 – The Map[edit | edit source]

Please note. This honour has had alterations as the South Pacific Division has reviewed the honour and made changes in 2010

1.1 Know the following[edit | edit source]

a. What is a topographical map?[edit | edit source]

Basically a view from on top. Symbols and colours to represent true features on the land.

b. What is found on a topographical map?[edit | edit source]

Key, contour lines, scale, grid system, trigs, G-MA information, map series and name

c. Give three uses of a topographical map.[edit | edit source]

Navigation, route planning. Identifying physical land features. In emergency situations when visibility is reduced.

- Description of land surface showing the shape of the land.

- Shows positions of roads, fences, and other man made objects.

- Indicates a pictorial view from above

1.2 What is an orthophoto map?[edit | edit source]

An orthophoto map uses aerial photos as the background with symbols and other information overlaid. Find a picture of one using Google.

1.3 Be able to recognize twenty signs and symbols found on a topographical map, giving some in each of the following categories[edit | edit source]

a. man made[edit | edit source]

b. water feature[edit | edit source]

c. vegetation feature[edit | edit source]

Most good tramping (hiking) maps will have a key showing lots of different symbols representing various features.

Man made:

Roads: Highways, sealed roads, gravel roads, 4wd tracks (Dryweather roads), walking tracks. Bridges, cuttings, embankment.

Railway: single track, multi track, stations, cuttings, bridges.

Miscellaneous: buildings, churches, schools, structures, cemetery,light house, ship wreek, electricity lines and poles, fences, mines open & underground.

Relief features: contour lines, permanent ice, rock outcrops, boulders, banks, trig station, alpine scree, glacier.

Water feature: marsh, river, lake, sea, small stream, ditch, spring, mangrove, getty, break water, gravel, sand, mud, dam, waterfall, sink hole.

Vegetation features: native forest, exotic coniferous (and non coniferous) forest, orchard, vineyard, shelter belt.

1.4 Know and explain the following as they relate to elevation[edit | edit source]

a. Elevation.[edit | edit source]

b. Contour interval.[edit | edit source]

Coloured orange. Points of same altitude In the NZ old inch to a mile series 1:63360 the difference in height between contours was 100 feet. In the new (2005) metric series 260. the interval is 20 metres.

c. Ground formations (Valey, Ridge, Spur, Bluff or Cliff, Saddle, Sholder, Escarpment, Knoll, Brow) defined by their contour lines[edit | edit source]

This picture of part of the Milford Track gives some idea of the contour lines on the Hollyford Map. These are glacier-formed valleys, U-shaped with steep sides. The Milford, Routeburn and Hollyford tracks are in the same area in Fiordland.

1.5. Know and explain the following as they relate to distance[edit | edit source]

This is a horizontal distance as the crow flies. It is not always a very accurate estimation of the amount of land between two points (land distance). Land distance depends on terrain. Land distance = horizontal distance + (contour interval x number of contour lines).

a. How is distance defined.[edit | edit source]

b. The map scale[edit | edit source]

Relationship of the horizontal distance between two points on the map and the horizontal distance on the ground in real life. This is shown as a ratio

c. How to measure linear distance[edit | edit source]

Look at the map scale to calculate the real distance

d. How to estimate land distance.[edit | edit source]

The land distance can be estimated by the following: L = H + (CI x n)

Where: L = land distance between points A & B

H = horizontal distance between points A & B

CI = contour interval of the map

n = number of contour lines crossed between points A & B

1.6. Know and explain the following as they relate to a map grid system.[edit | edit source]

a. What is the grid system?[edit | edit source]

To accurately locate reference points on a map using a set of 6 numbers.

b. What is a six figure grid reference?[edit | edit source]

Grid numbers are a two digit number at the end of each grid line. However a grid reference must contain 6 numbers. 3 from the horizontal and 3 from the vertical. The third digit is the approximate distance in tenths between the two nearest grid lines. Always give the longitude first then latitude.

c. Rules for reading grid references.[edit | edit source]

A typical grid reference would look like 355884. Most topo maps would explain how to do this on the borders.

1.7. Know and explain the following in relation to map reading[edit | edit source]

a. Grid North[edit | edit source]

The direction of the North Grid lines run vertically on the map so the top of the map would be grid north.

b. True North[edit | edit source]

Usually grid north and true north are the same on topographical maps, but in some instances this is not the case, especially as the maps get closer to the arctic regions. Check the map do NOT guess or assume or you will be geographically embarrassed (i.e. lost). Check the magnetic delineation on the map.

c. Magnetic North[edit | edit source]

The direction to which the red pointer needle on the compass nearly always points. The difference between true North and magnetic North is called the magnetic declination or G-MA (Grid Magnetic Angle)

d. Declination[edit | edit source]

The compass needle aligns itself with the Earth's magnetic flux (lines)of force passing through the place you are standing. The difference between true north and magnetic north is the G-MA angle. This changes with the Earth's magnetic field variations. The G-MA must be considered when using a compass to orientate a map. The map will give a value and time calculation so you can work the value of the angle.

e. Grid Magnetic Angle (G-MA or GMA)[edit | edit source]

Section Two – The Compass[edit | edit source]

2.1. What are the eight major points of the compass and their bearings?[edit | edit source]

| 1 | N | 0°/360° |

| 2 | NE | 45° |

| 3 | E | 90° |

| 4 | SE | 135° |

| 5 | S | 180° |

| 6 | SW | 225° |

| 7 | W | 270° |

| 8 | NW | 315° |

2.2. Identify the type of compass most popular with bushwalkers.[edit | edit source]

I have come to understand that there is a difference between Northern Hemisphere compasses and Southern Hemisphere compasses. I am free to be corrected on this point. It may pay to check if you are country hopping. Most people I know use a Silva brand or similar. Plastic transparent base. Scales, glow in the dark dots. Some are good for Orienteering as they have triangles and circles cut out of base for marking controls on your map.

2.3. Know the parts of an orienteering compass.[edit | edit source]

The Silva compass is a very good one to use on map work. It has a plastic see through base. To get a good picture with a label of what each part is called cheek out Google images.

1. Scales. Inches and mm

2. Transparent base plate

3. North on dial

4. Magnetic needle north end

5. Liquid filed housing with graduated dial and orienting line

6. Direction of travel arrow

7. Magnifying lens

8. Index pointer (for setting bearings and reading

9. Orienting arrow

10. Dial graduations 360 deg

2.4. Know and explain the following as they relate to Grid Bearings and Magnetic Bearings[edit | edit source]

a. What are Bearings?[edit | edit source]

Directions expressed in degrees from North. A circle has 360 degrees. So North is 0 degrees.

There are true bearings with the North Pole as the reference point. There are also magnetic bearings taken from a theoretical Magnetic North. But in reality you are influenced by a local magnetic flux. The magnetic forces around our planet are not always even. So when giving a bearing always state if it is true or magnetic.

On a map there usually are grid lines and bearings can also have them as the bearing reference. (usually gridlines are true North or very close to it. It is wise to check)

b. How to calculate Grid Bearings from the map[edit | edit source]

i. Place long edge of compass along the bearing desired.

ii. Hold compass base on the map and turn compass housing until orienting arrow is parallel to grid lines.

iii. Correct for G-MA

iv. Hold compass at waist and turn until needle aligns with orienting arrow. Travel in the direction of travel arrow.

c. How to convert a Grid Bearing to a Magnetic Bearing[edit | edit source]

Point the travel arrow towards where you want to go. Rotate compass housing until the orienting arrow is directly below the magnetic needle. This will give the magnetic bearing.

d. How to convert a Magnetic Bearing to a Grid Bearing[edit | edit source]

e. How to take and march on a Magnetic Bearing[edit | edit source]

Set the compass to the required magnetic bearing. Follow the travel arrow. It is good practice to look in the direction of travel and find a notable feature in the distance then the compass can go back in your pocket. If visibility poor or nil use a rope and a runner to go ahead and caste about till the runner on the desired bearing. Then move to the stationary runner following the tight rope. If no rope use same method but go by sight, not letting the runner out of your sight you position him in line with the travel arrow.

f. What is Slipping and how to correct for it?[edit | edit source]

When traveling on a compass bearing large obstacles or the lie of the land can put you off course usually with out you knowing. The result is that after the obstacle you are really traveling on a parallel course to that you started on. This is called slipping.

To correct this you need to have the starting point in view. So without adjusting the compass turn around to point in the general direction of the starting point. Then move sideways so that the needle (south end) points to the orientation arrow. You are now in the original line and can continue on course. If the starting point is not visible you would have to find your true position by doing a resection and then moving to where you should be so you can continue on the original course.

g. How to take a back bearing[edit | edit source]

Used to check back where you have come from. The bearing should be 180 deg different or the compass can be turned around so that the white end of needle aligns with the orienting arrow. (Check for slipping)

2.5. Know and explain the following in relation to Resection.[edit | edit source]

a. What is resection?[edit | edit source]

Used to locate your position on a map by locating major recognisable land features and working out where you are.

b. The two-bearing method of Resection.[edit | edit source]

Take two back bearings from known features. Remember to transfer backward for G-MA. The point where the two or more bearings cross is your location. Of course is accuracy is not an issue you could look at the features around you and find them on the map and work out where you are in relation to the sighted features.

c. The three-bearing method of Resection.[edit | edit source]

The same as above but using three features. The more apart they are the better.

2.6. Know and explain how to Orient your map by[edit | edit source]

a. inspection and[edit | edit source]

Have a good look about you.. Mountain peaks, passes, rivers valleys. Put map on ground turn ot about to get it to match what is about you.

b. by compass.[edit | edit source]

Work out your particular GM-A

Set the compass housing to the G-MA so that the compass replicates the north arrow diagram: that is, the direction of travel arrow points generally along the grid north arrow and the orienting arrow points generally along the magnetic arrow. Leaving the compass set, place it anywhere on the map with the long edge along one of the grid lines and with the direction of travel arrow pointing to Grid North. Disregard the compass needle. Without moving the compass, rotate the map until the North end of the compass needle aligns over the orienting arrow.

Section Three – Direction without the aid of a Compass[edit | edit source]

3.1 Demonstrate how to find directions without a compass using the Southern Cross (ie. Crux) method[edit | edit source]

I have also included a couple other methods as well for daytime and night as extra bonus material.

1. Watch.[edit | edit source]

Southern Hemisphere method only.Point the 12 to the sun. Halfway between the hour hand and the 12 is North. You still have to use your intelligence for this as early morning time and evening time care must be taken as to which half you use. E.g. 8am sun is rising in the East; point 12 to the sun North is halfway between the 8 and the 12 at the 10. BUT late evening the sun is heading to set in the west say time is 8pm you point the 12 at the sun. North is halfway between the 8 and the 12 at the other side of watch at the 4. This should be used only as a guide as in some countries the real time has been adjusted and sometimes there is daylight saving time etc.

I use this method as it saves getting out the compass or even carrying one. One draw back is that you do need to know where the sun is. Usually when you are lost it is getting dark and there is no sun.

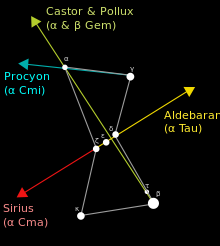

2. Southern Cross.[edit | edit source]

With the lack of a significant pole star in the southern sky (Sigma Octantis is closest to the pole, but is too faint to be useful for the purpose), two of the stars of Crux (Alpha and Gamma, Acrux and Gacrux respectively) are commonly used to mark south. Following the line defined by the two stars for approximately 4.5 times the distance between them leads to a point close to the Southern Celestial Pole.

Alternatively, if a line is constructed perpendicularly between Alpha Centauri and Beta Centauri, the point where the above line and this line intersect marks the Southern Celestial Pole. The two stars are often referred to as the "Pointer Stars" or "White Pointers", allowing people to easily find the top of Crux.

The junction of these two lines is the SCP Southern Celestial Pole. If you were at the South Pole this would be directly above you. This is the point where the night sky revolves around. Point to this spot then lower your arm to the horizon. Where you are pointing is South.

This is the only method I use at night. The crux is easy to find usually, as long as you are not in a valley which blocks out the essential constellation.

3. Orion[edit | edit source]

Orion is not visible all year in the southern hemisphere

To find south we need to look to Orion. Best when it is high in the sky. Find the head stars belt and sword. The line of the sword points closely to the Southern celestial pole (SCP) The line of the sword depending where you are will not point to south and as the night progresses further off the North South line. So to use Orion as a navigational tool you will have to know where the SCP actually is so to do this use the method determined in finding South by use of the Southern Cross. Once you have determined where the SCP is in relation to you point at it then drop your arm to the horizon you are pointing to South.

I never use this method.

4. Shadow Stick.[edit | edit source]

This method can be a waste of time. We all know the sun rises in the East and sets in the West. The stick shadow shows you this. Also when the sun is at its zenith the highest it gets in the Southern Hemisphere look at the sun and it is towards the North the opposite in the Northern Hemisphere. So we learn that at mid day is the best time to find North (or South).

But if you must... place a stick in the ground on an open area. Mark the shadows at times through out the day. From this you can find North or South (depending what side of the equator you are on) from the shortest shadow and also East and West by drawing a line from the ends of the longest shadows assuming you had an early morning and late evening marking with equal time from mid-day. But for this you have to be lucky to have sunshine for most of the day, which usually is not the case if you are lost. Anyhow it is something to know if you do not have a watch to know when real time mid-day is and you have a full day to hang about.

An alternative method to this as suggested to me by a major contributor to these pages.

Get a stick. Point the stick end to the sun while pushing stick into the ground so it free stands. Observe the shadow in the first 15 minutes. The base line of the shadow will be the East West line. A perpendicular line off the base line towards the sun side will be North. Over a longer period you will be more accurate.

Section Four – Practical[edit | edit source]

4.1. Demonstrate how to[edit | edit source]

a. Read six figure Grid Refences. Refer to Requirement 1.6c.[edit | edit source]

b. Calculate a Grid Bearing from the map. Refer to Requirement 2.4b.[edit | edit source]

c. Convert Grid Bearing to a Magnetic Bearing. Refer to Requirement 2.4c.[edit | edit source]

d. Take a Magnetic Bearing. Refer to Requirement 2.4c[edit | edit source]

e. Locate a position using Resection. Refer to Requirement 2.5[edit | edit source]

[edit | edit source]

4.3. Prove your ability in the use of a map and compass by following a cross-country course with at least ten given readings or control points.[edit | edit source]

Keep a log detailing[edit | edit source]

*Grid reference[edit | edit source]

*Grid and Magnetic Bearings[edit | edit source]

*Records of actual course taken[edit | edit source]

The exercise is not the ability to travel exactly on a bearing between the two points, this is usually impossible in rough wilderness areas. Following an established trail or not so established between the two points would be permissible.

It is not the intention of the honour that the terrain is almost impassable. Remember to have the safety of the participants in mind. There is no set distance for this 10 stage course. It is suggested that controls be more than 200m apart but the next control not visible from previous control.

Have lots of fun and save lots of memories.

References[edit | edit source]

- Book:Adventist Youth Honors Answer Book/Honors

- Book:Adventist Youth Honors Answer Book

- Book:Adventist Youth Honors Answer Book/Skill Level Level 2

- Book:Adventist Youth Honors Answer Book/Honors Introduced in From GC 1956 This version SPD 2010

- Book:Adventist Youth Honors Answer Book/Recreation

- Book:Adventist Youth Honors Answer Book/South Pacific Division

- Book:Adventist Youth Honors Answer Book/Completed Honors